[/caption]

[/caption]DESCRIPTION

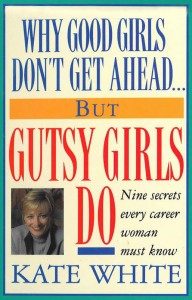

The editor-in-chief of Redbook magazine shows businesswomen how to talk like winners, face trouble directly, take smart risks, and bend the rules to their own advantage, offering personal anecdotes from forty high-profile career women.REVIEWS

Female women are back; just-like-a-man is out. Don't be a goody-goody; knock 'em dead instead. Here in part is the message of this lively and unsparing guide for the '90s by Redbook's editor-in-chief, who isn't afraid to talk about herself and the secrets of her success. Citing surveys, academic studies, the ways of 40 other successful women and her own rollicking career triumphs, White proclaims a new outlook for traditionally self-effacing "good girls" in today's workplace. To offset dwindling male "guerrilla chauvinism," she advises women not to take setbacks personally but to "get some zip," focus on the work, dare to wear (borrowed) $400 dresses to crucial meetings and (secretly) study their own miens and mannerisms on videotape; plus many more tips.PREVIEW

[lyrics]CHAPTER ONE

The Myth of the Good Girl

The day Julia Roberts's publicist telephoned my office and told me that Julia wondered what I had against her. I began to make an interesting discovery about myself—though I didn't realize it at the time.

First, let me give you the background on how Hollywood's hottest star had come to hold me in the same regard she had for the stripper Kiefer Sutherland was dating during their engagement About a year before, as the editor-in-chief of McCall's, I'd commissioned an “unauthorized” cover story on Roberts, focusing on her mysterious hiatus from movies after she'd called off her wedding to Sutherland. It had sold like crazy on the newsstands Now, the first rule of magazine newsstand sales is that if something works, you do it again—and that was my game plan exactly. The publicist had been furious about our first effort, and as soon as she got wind of the fact that we were planning yet another unauthorized cover story on her star client, she called me to protest. She said angrily that she'd always assumed that McCall's had high journalistic standards and wouldn't stoop to publishing a celebrity profile without interviewing the subject. She claimed that Julia had even asked her, “Does the editor of McCall's have something against me?”

Though most of our cover stories were interviews with celebrities, occasionally, when we were turned down by someone (as we had been by Roberts), we'd report the story using a variety of other sources. You'd be surprised at how many friends and relatives are willing to gab, though you also can discover that people have been warned to keep their mouths shut. In this particular case, the publicist was telling everyone, right down to the dolly grip operators on Julia's latest movie, not to talk to us, and so far this had resulted in a severe dearth of dirt. When I'd checked on the progress of the story one day, the researcher had looked up woefully from her desk and announced that the only new information she had was the fact that Roberts's nickname in high school supposedly had been “Hot Pants.” Oh great, I thought. There was cover line potential (IS JULIA HAUNTED BY HER STEAMY PAST?), but the article would be one paragraph long.

Despite such roadblocks, I knew that eventually we'd end up with something. In the long run, this type of story often turns out to be the juiciest and most fun to work on because you've got to be more creative and resourceful.

Unfortunately Roberts and her publicist weren't seeing the fun in all of it. This was hardly the first time I'd had trouble with a cover subject. I once had to kill a cover story on a television star because the photographs came back making her look about as glamorous as a spokesperson for National Tartar Control Month. We heard from the star's publicist that she was very, very miffed. But this was the first time that I had been chewed out personally on the phone. Several days after the conversation with the publicist, I got a letter from her reiterating her annoyance. It was clear that Julia would certainly never agree to an interview with McCall's, and neither would any of the publicist's other clients. In fact, it almost sounded as if she was going to warn off all of Hollywood. Did this mean that I'd better get Marie Osmond and ha Zadora on the phone fast because they'd be the only women I'd be able to recruit for a cover?

As I was packing up to leave the office that night, my assistant looked up at me and asked, “Does it bother you to get a letter like that? Aren't you worried that she might really do something?”

“No, it doesn't bother me,” I laughed. And I meant it.

A few years before it would have bothered me. In fact, it might have even tortured me to know that someone was really mad over something I'd done and might say rotten things about me to other people. I liked being liked and hated not being liked—and I probably would have walked around for the next few days with a sense of dread, like the kind you experience when you are in the Federal Witness Protection Program. But those feelings just didn't happen anymore Somewhere along the way I had stopped worrying about what people thought about me.

MY MOMENT OF DISCOVERY

About a week later, a friend of mine in the company steamed into my office and handed me an article from the trade magazine Executive Female called “Why It Doesn't Pay to Be a Good Girl.” The piece had been written by a woman who once had worked for me at another magazine and I assumed that was why my friend was showing it to me. As I glanced through it, however. I discovered, much to my amazement, that I was the focus of the story.

In the article the writer described herself as the quintessential good girl, someone who had always done what she was told, tried to make everyone like her, and taken on as much work as possible. She'd assumed that one day she'd be rewarded for such noble efforts. But much to her shock she'd seen many of the spoils she thought she deserved go to women like me. The author claimed I was the antithesis of a good girl, someone who broke the rules, didn't give a damn what people thought, made quick, bold decisions, and delegated all the grunt work to others (keeping control of the delicious, exciting stuff for myself). She said, with regret, that I had become her role model.

At first I thought, She's got it all wrong. I'd certainly heard psychologists talk about the concept of the good girl, the kind of woman who worries so much about pleasing other people that she neglects her own needs. Years before, I'd even written an article for Mademoiselle on the subject. If anyone had asked, however, I probably would have said automatically that I was a good girl myself.

But the more I considered it, the more I could see for certain that I was not a good girl. I was decisive, almost fearless, and I didn't spend time worrying about other people's opinions of me. That, after all, was why I hadn't agonized over the comments of Julia Roberts's publicist. I also realized that it was the reason for much of the professional success I'd had in the past few years.

Once, I had been a good girl. In fact, it's safe to say I'd been one for a huge chunk of my life. But over time—and especially during the past six years—I had changed rather drastically. What was I now? There seemed to be only one phrase for it:

I had become a gutsy girl.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOU FOR A MINUTE

If you bought this book, you probably responded on a gut level to the words good girl in the title. It's an expression that most women react to viscerally because we heard it over and over as we were growing up. Every time we jumped in a puddle with our party shoes on or cut off our doll's hair with nail scissors or blew bubbles into our milk or clobbered our little brother with his own weapon after he'd repeatedly tortured us, we were told. “Be a good girl,” or “Good girls don't do that.”

To be a good girl you had to follow the rules, act nice to everyone, and never talk back to your elders or superiors. Over time we learned to keep quiet and walk around the puddles.

Why did we acquiesce? Because throughout childhood and adolescence, not only were there reprimands for failing to be a good girl, there were also clear rewards for being one: we were applauded by parents and teachers and neighbors and just about everyone else, with the exception of guys in motorcycle jackets with tattoos that said Born to Raise Hell.

Now that you're out in the real world, good-girlism may appear to be working nicely, too. Bosses pat you on the back for a job well done and co-workers constantly say things like, “Thanks, you're a doll.” But chances are you may already have begun to detect a fissure in the foundation of the good-girl way of life. You may, for instance, have come to feel the stress and strain that occurs from always trying to please, from constantly playing it safe, from being the one who never fails to get stuck with the dirty work There is also a frustration from never confronting those who try to steal your thunder or your ideas. Think about it. Haven't there been evenings when you've left the office with your cheeks aching from keeping a frozen smile on your face all day?

I am here to tell you that the aching cheeks are the least of your problems. The real tragedy is that, despite the pats on the shoulder and the compliments, being a good girl actually undermines your career and prevents you from achieving maximum success. Sure, doing exactly as you're told, being nice and acting modestly worked at home and in school, but once you get out into the world of work, the dynamics change and you need to approach matters in a whole new way. The rewards go to women who make their own rules, take big chances, toot their own horns, and don't worry if everyone likes them.

This information may seem to fly in the face of reason. Right there in your office are probably loyal female managers who have done what they were told and have been promoted for doing so. But such “good” behavior will only get you so far. Studies show that managers tend to avoid risks, maintain momentum, focus on the short term, and work at balancing interests; leaders, on the other hand, take risks, stir things up, think long term, and pay attention to what they believe works best. To break out of the pack and become a real star in your company, you have to leave the Goody Two-Shoes behind—and become a gutsy girl. This approach is more essential today than ever. Currently, there's a glut of managers due to corporate downsizing and rightsizing. Though there are more routes to the top for women these days, the increased competition for these spots makes the proportion of opportunities smaller—and only the most dynamic employees will make the cut.

Was your last raise what you'd hoped for? Are you considered one of the dynamos in your department? Do you get the choice assignments? Does your boss's boss know who you are? Do you feel recognized for your contributions? Do you find your work pleasurable and exhilarating? If the answer to most of these questions is no, you may have worried at times that it reflects a lack of talent or skill on your part. But that may not be the case at all. You may simply be too good for your own good.

“BUT DOES THIS MEAN I'M SUPPOSED TO BE BAD?”

Now, at this point you may be saying, “Whoa, wait a minute. Are you suggesting I Start behaving like the Shannen Doherty of corporate America?” Not at all. A gutsy girl isn't a bad girl. She can be conscientious, hardworking, kind to her subordinates, and respectful of authority. But she also takes risks, charts her own course instead of doing exactly what she's told, asks for what she wants, gives the grunt work to someone else so she can focus on what's important (and fun), makes certain that the right people know of her accomplishments, and doesn't spend every moment trying to please people. Here's what a good girl and a gutsy girl look like side by side:

A good girl … A gutsy girt …

1. follows the rules; 1. breaks the rules—or makes her own;

2. tries to do everything; 2. has one clear goal for the future;

3. works her tail off; 3. does only what's essential;

4. wants everybody to like her; 4. doesn't worry whether people like her;

5. keeps a low profile; 5. walks and talks like a winner;

6. waits patiently to get raises and promotions; 6. asks for what she wants;

7. avoids confrontations; 7. faces trouble head-on;

8. worries about other people's opinions; 8. trusts her instincts;

9. never takes risks 9. takes smart risks.

When you bought this book, I don't think it was simply because the phrase good girl in the title hit home. I suspect it's also because the phrase gutsy girl captured your fancy. There's a part of you that's ready for change, that wants much more—and has begun to suspect you need a gutsier approach in order to get it.

But if you've been a good girl all your life, you're probably wondering how you can run against the grain of your nature.

I believe that even though you've followed the good-girl program growing up, it's not necessarily the response that's most natural for you. I believe that inside most good girls, there's still a spirited, adventurous, bubble-blowing, puddle-jumping, hair-scalping girl biding her lime. When your face aches from smiling too much or your stomach hurts after a pathetic raise, it's just a signal of the tension from trying to keep her buried. Let me tell you a little bit about my own evolution.

HOW I WENT TO BED A PUSHOVER AND WOKE UP A GUTSY GIRL

Sometimes I feel I was the original Goody Two-Shoes. As a fourteen-year-old, while many teenagers I knew were entering a defiant period, the only “wild” thing about me was that I set my hair with pink sponge rollers and Dippity-Do, and when combed out it looked like I had a woodchuck sitting on my head.

Oh, I longed to be wild, but I was afraid to break the rules. Here's a perfect example: My parents were fairly protective and they made my brothers and me wear boots in winter even if there were only two patches of snow on the sidewalk. Years later I mentioned to my brother Jim how embarrassed I'd felt trudging along in what seemed like forty pounds of rubber while everyone else had on Keds.

“Didn't it bother you?” I asked.

“Nah,” he replied. “Mike and I always left our boots at Charlie Hagstrand's in the morning and picked them up on the way home.”

It had never, not even once, occurred to me to break the rules that way.

My goody-two-boots tendencies continued all through school, as well as through the early years of my career. Sometimes I'd break out and do something surprisingly daring, and the result would be fabulous. But rather than think that gutsiness had worked in my favor, I'd feel as if I'd managed to get away with something and maybe I shouldn't try it again.

I started my career at Glamour magazine after winning their Top Ten College Women contest. After working at Glamour for six years as an editorial assistant and then a feature writer, I moved to Family Weekly (now USA Today Weekend), as senior editor and eventually executive editor. From there I went to Mademoiselle, where I was the executive editor in charge of the articles department. I was a hard worker, and though my boss considered me fairly spunky. I always minded my p's and q's. That approach. I assumed, was serving me well.

Then, just after I was promoted to the number-two position at Mademoiselle, I had a baby and everything began to change for me. I'd expected that in my case being a working mother would be fairly smooth sailing. My boss, an extremely smart and creative editor-in-chief, had a tendency to go hot and cold on employees, but I'd managed to remain in her good graces by following orders and agreeing with all of her insights At times I felt like one of those dogs with the bobbing heads you see in the back windows of cars, but at least I felt safe in my job.

As soon as I returned from maternity leave, however, my boss turned icy toward me. After several years on the hot list, I suddenly had freezer burn. On my seventh day back, she called me into her office and said she was uncomfortable with the fad that I was now leaving at 5:00 P.M. every day and warned me to stay until at least six in case any big ideas came up during that time period. She certainly had the right to say it, but to me it was a ludicrous request. We were, after all, a fashion and beauty magazine for twenty-four-year-olds. It wasn't as if someone was going to burst into my office at 5:45 screaming. “Stop the presses! Somebody just invented thong underwear!” Though I agreed to her demands. I left that night determined to get a job that would allow me to come and go as I pleased so I could spend enough time with my child. Four months later, after lots and lots of hustling, I was the editor-in-chief of Child magazine.

And that's when I started to scrutinize the way I approached my work and when I began, without even realizing it, to kick the good girl out of my system. You sec, I really didn't have a choice. I wanted very much to succeed at Child but I also knew it would be tough to be effective in such a powerful position and also be a conscientious mother. I'd already discovered how crazy life was as a working mother. One night after I'd gotten home from Mademoiselle, I'd hurriedly dressed Hunter in his snowsuit so I could take him with me grocery shopping. As I pushed the stroller through my apartment building lobby, I noticed in the mirror that in my frantic state I'd put his little ski cap on my head. That moment seemed to symbolize the nuttiness of my life.

It was clear to me that in order to pull it off. I would have to change my work style. I was going to have to learn to make instant decisions, delegate like crazy, focus on the big picture rather than the details, and be adventurous in my thinking And I was going to have to cease caring if people “liked” me.

So that's what I did. I took a gutsier approach to everything And what's amazing is that as I experimented with this style, I discovered that it felt far more natural to me than the Little Miss Nice role I had played for so long.

A year and a half after going to Child, I was recruited to be the editor-in-chief of Wording Woman. I was a little more than seven months’ pregnant when I got the job; the owner said he chose me because of my gutsy new plan for the magazine And a year and a half after that, I was recruited back to the New York Times Company to be editor-in-chief of McCall's The good girl had bitten the dust.

After about four years at McCall's I was chosen last October to be the new editor-in-chief of Redbook, which had been brilliantly fashioned by Ellen Levine into a magazine for smart, sexy, gutsy women. I couldn't ask for more.

THE TRIPLE BONUS OF BEING A GUTSY GIRL

Once I began to think about my transformation to gutsy girl and reflect on how it had affected my professional life—my whole life, for that matter—I decided I wanted to share what I have learned. This book is filled with strategies on how you too can become a gutsy girl. They come not only from me but from some of the very successful women I have met through my work.

A word of caution: Being gutsy is not without its consequences. It's not unlike putting on Rollerblades instead of walking shoes. You're going to get there faster, the ride will be exhilarating, and yet there's a chance of bruising your shins or even breaking your elbow. You'll find, however, that your new skills as a gutsy girl can help you deal with any flak that you get from taking chances.

You'll discover, as well, three amazing dividends from following the strategies in this book. The first I've already talked about: your career opportunities will open up dramatically as you begin to be bolder and slop trying to please everyone but yourself Second, you will find yourself less a prisoner of your work as you learn to delegate, take shortcuts, and give yourself permission to relax. Being a gutsy girl actually has given me more personal time.

And finally you'll feel an amazing sense of relief as you let the gutsy girl out from her hiding place inside of you. It's wonderful to go home at night and not have to feel the ache in your cheeks from holding a frozen smile in place all day long.

CHAPTER TWO

Are You Trapped in the Good-Girl Role?

I hope by now you're itching to read the strategies in this book and embark on a gutsier approach to your career. But before you do, it's important to do a little prep work.

First, you should spend time thinking about how your good-girl habits evolved. When you trace the pattern backward it's not only illuminating, but you're likely to end at a point in time when you were spunky, adventurous, and unafraid—and that can be very inspiring.

Next, you should figure out how the good girl in you operates. When is she most likely to take over? What effect has she had on your career up until now? Warning: It may be less obvious than you realize. Good-girlism, you see, is very sneaky, and wears a variety of surprising disguises.

WHERE DO GOOD GIRLS COME FROM?

Good girls, I believe, are made, not born. In the past decade there's been a lot written about how women learn to put their own needs last and suppress their voices. Much of my understanding on this subject comes from conversations I've had with Ron Taffel, Ph.D., an extraordinary child psychologist and author of Why Parents Disagree, who writes “The Confident Parent” column for McCall's. Recruiting Dr. Taffel was one of the first steps I took after I got the job, because to me he had the freshest, most exciting views in the field of parenting. He works with individual kids and parents in therapy, and he also runs workshops for parents across the country.

According to Dr. Taffel, the seeds of the good girl are planted very early as a daughter observes the way the individuals in her home interact with each other and absorbs the messages her parents send.

While watching her mother day in and day out, she discovers the thousands of ways her mother takes care of everybody else. “A mother assumes primary responsibility for her family's needs,” says Taffel. “When a father does participate, its known as ‘helping out.’”

The mother, even if she has a job, makes the arrangements for school, for play dates, meals, holidays, celebrations, dentist and doctor appointments, vacations, and trips to relatives. She buys the clothes, the underwear, the shoes, the toothbrushes, the birthday gifts (for her own kids as well as her kids’ friends), the books, the Play-Doh and the paint sets. She drives for the car pool, makes the snacks, applies the Band-Aids, wipes the noses, cleans up the spills and messes, supervises the homework, calls the teacher, gets the camp applications, writes the thank-you notes. … It never stops.

A mother's responsibility includes not merely doing all these things, but constantly thinking about them, keeping a mental calendar and to-do list going day and night—what Taffel calls “The Endless List of Childrearing.” This mental list is her province alone. It's safe to say that if she doesn't ever get around to calling the orthodontist for a consultation, someone will have a lifelong overbite.

She is also what Taffel calls the family “gatekeeper,” the possessor of critical information. If a child wants to know where to find a clean pair of socks or a library book he was reading, there is only one parent who knows for sure.

The message a daughter hears through all this is that one of the most important jobs a female has is considering and taking care of others’ needs, and in the process that often involves putting her own needs aside.

That's not all that's going on. In her home. Dr. Taffel explains, a daughter is also encouraged to be “the best little girl in the world.” When she takes a toy from another child, talks back to her parents, refuses to follow an order, she is told. “That's not nice.” or “Be nice,” or “Be a good girl.” Because her not-so-pleasing, aggressive side is so often admonished, she may become ashamed of it—and eventually repress it.

“Anger is the signal that it's time to be assertive,” says Dr Taffel, “but if you are told repeatedly that it's wrong to be angry and you don't let yourself feel anger, you lose the signal that you need to let your assertiveness take over.”

Boys, too, are admonished for their bad behavior, but it's often done with a wink or what Taffel calls a “double look.” It's as if the parent is saying, “You shouldn't have done that—but I'm proud of you because you did It means you're not a wimp or a sissy.”

Now, certainly this was the way it used to happen, but haven't things changed? Aren't we giving girls a whole new set of messages?

Marsha Gathron, associate professor of health and sports sciences at Ohio University, who has studied self-esteem in young girls, says that she feels the problem has gotten even worse. “Young girls are being hit just as hard today if not harder than several generations ago,” she says. “Many of the same variables are still there that make girls doubt themselves. Plus we no longer have the strong family ties that might help some girls get beyond the messages.”

Dr. Taffel believes that though we've made progress in raising kids without the strong sexual stereotyping of the past, the good-girl message still comes through loud and clear, not only at home, but through television, advertising, books, and other conduits of society's attitude. Sometimes it's done with such subtlety that we don't even notice.

Consider the latest edition of the classic board game Chutes and Ladders, billed as “an exciting up and down game for little people.” In the game, players (kids ages four to seven) move along a playing board, sometimes landing on ladders that allow them to take shortcuts, and sometimes landing on chutes that force them backwards. The ladder squares depict kids being rewarded for good behavior and the chute squares show them facing consequences for bad behavior.

Here's where it gets interesting. There are twelve boys on the board, compared to seven girls. In the examples in which the boys get to move up the ladders, they are being rewarded for a variety of good behavior, including some heroic stuff: returning a lost purse, saving a kitty. The girls are all rewarded for housework: sweeping a floor, baking a cake. As for bad behavior, there are twice as many high jinks for the boys. The girls’ naughty behavior, what little there is of it, includes eating too much candy and carrying too many dishes. The boys’ is all action oriented: riding a bike without holding on, breaking a window playing ball, and walking in a puddle. Twenty million sets of Chutes and Ladders have been sold since its creation.

Even when we attempt to be fair, we blunder. Take a look at the hugely successful book series for young kids, the Beren-stain Bears. The books are charming, informative, and full of politically correct references to nurturing dads and working moms. But here's what Sister Bear and Brother Bear fantasize about in Trouble with Pets, published in 1990, when they're anticipating getting their first dog.

Sister thought about dressing it in doll's clothes and pushing it in her doll carriage. She thought about introducing it to her stuffed toys. Perhaps they could have a tea party. … Brother's thoughts were quite different; he thought about winning the blue ribbon at the Bear Country Dog Show. He thought how fine it would be to shout “Mush!” as his great dog pulled him through the deep snow.

In other words, Sister wants to sit around looking pretty and acting pleasant. Brother wants to be a leader and a winner.

THE GOOD GIRL GOES TO SCHOOL

Any good-girl message that comes through at home soon gets reinforced at school. Some research over the past two decades has revealed that there is extraordinary gender bias in schools, and that it continues in strong force today. Social scientists Myra Sadker, Ed.D., and David Sadker, Ed.D., authors of Failing at Fairness: How America's Schools Cheat Girls, who have conducted twenty years of research, say that girls are systematically denied opportunities in areas where boys are encouraged to excel, often by well-meaning teachers who are unaware of what they're doing. Male students, the Sadkers report, control classroom conversation. They ask and answer more questions. They receive more praise for the intellectual quality of their ideas. Girls, on the other hand, are taught to speak quietly, to defer to boys, to avoid math and science, and to value neatness over innovation, appearance over intelligence. In one school contest the Sadkers observed, the “Brilliant Boys” competed against the “Good Girls.”

In the early grades, girls routinely outperform boys on achievement tests, but that's only one part of “schooling.” “There's the official curriculum, which calls for doing well on tests and homework and getting good grades,” says David Sadker, “but then there's also the hidden one. This curriculum involves speaking up in class, raising questions, offering insights. It helps a student develop a public voice. Girls aren't encouraged to develop this public voice. They are rewarded for being nice and being quiet. Their high grades lull them into a false sense of security that they are doing what they must to be a success. It's only later that they pay a price for having been encouraged to be a spectator, to not speak up.”

By the time girls graduate from high school, they lag, as a group, far behind their male counterparts.

Year after year of these messages, both in school and on the home front, can become internalized. The most widely known research on what happens to school-age girls is by Carol Gilligan, professor in the Human Development and Pyschology Program at the graduate school of Education, Harvard University. In studies Gilligan found that there is a “silencing” of girls that occurs as they move from the elementary grades into junior high. Up until that point, she says, they seem filled with self-confidence and courage, and they're candid about what they feel and think and know. But as they enter midadolescence and become aware of society's expectations of them, they start to get more tentative and conflicted. The conventions of femininity require them to be what Gilligan calls “the always nice and kind perfect girl.”

Thus, Gilligan says, girls experience a debilitating tension between caring for themselves and caring for others, between their understanding of the world and their awareness that it is not appropriate to speak or act on this understanding. They are uncomfortable about how people will feel if they get mad or aren't “nice.” The girl who is insistent on speaking and desires knowledge goes “underground,” says Gilligan, or is overwhelmed.

When girls look to grown women for inspiration, they may not get any help. Gilligan says that women, in the name of being good women, model for girls the “repudiation” of the playful, irreverent, outspoken girl.

Though some experts have criticized Gilligan's theories, I think many of us can't help but see ourselves when we read her words. You're automatically transported back into sixth or seventh grade, feeling the fatigue of always trying to please and the stress that results from constant vigilance over your own words and behavior. By the age of eleven or twelve you probably discovered the importance of being “liked,” and what that required. Popular boys are often boisterous and mischievous, but popular girls are generally careful about their words and their behavior. As soon as this sank in, you locked that smile into place and tried not to sound opinionated. You worried about what you were going to say before you said it, while you were saying it, and after you said it.

And come to think of it, you weren't really supposed to be saying much at all. You were told it was important to let boys do the talking and so you listened, smiled, listened. You learned quickly that no one likes a girl who hogs the limelight. And God forbid you ever did anything unconventional that would draw attention to yourself and make some loud bully of a boy suddenly take particular notice of you in class and decide that you were the one who would be crucified for your clothes or your complexion or your breasts.

I can remember extraordinarily well a moment when I began to shut down pan of myself in order to be liked. During my early grade-school years, I had this devilish streak in me, even though I was also pretty shy. In sixth grade this cute and cocky boy named Kevin transferred to our school and into my class. Everyone, boys and girls alike, fawned over him, and as the year went along he got kind of big for his britches. Where I grew up, in upper New York State, the first of May was celebrated by kids exchanging May Day baskets they made by pasting crepe paper on old oatmeal and saltine cracker boxes and filling them with candy. This particular May Day I decided I wanted to get Kevin's attention, but instead of fawning, I tried a more irreverent approach that I thought he'd appreciate as a cocky kid. I made the rattiest looking May Day basket with water-stained, ripped crepe paper, then filled it with stones, and left it on his desk just as everyone was coming in from lunch.

Well, you would have thought I'd yelled the words sexual intercourse at the top of my lungs. A hush fell over the class as kids realized what had happened, and once it was discovered I was the culprit, they looked at me in horror. I tried to make light of the situation, but that night I went home feeling something I had never experienced in school before: shame.

From that day forward I did my best to hold that little devil down. I got with the good-girl program that is reinforced all through adolescence. Abigail Cook, a friend of mine who is a trader on Wall Street, puts it this way: “If I could have hung a motto over my bed in high school it would have been: ‘Be nice, you'll be liked, you'll get married.’ “

Though many of Gilligan's theories were developed over fifteen years ago, educators and researchers say they see the same dynamics at work today.

Barbara Berg, dean of the upper school of Horace Mann, a private school in New York, and author of Crisis of the Wording Mother, says that she witnesses many young girls caught in the good-girl trap and unable to feel a personal sense of empowerment. “A girl who was being verbally harassed by some boys came to my office lately for help,” says Berg. “I suggested that one step would be for her to tell the boys that she didn't want them to do that. She said that she couldn't. She was wonted that if she did, they wouldn't like her.”

In school, a girl may find herself in a constant and draining state of either/or. You can be pretty or powerful, you can be popular or smart.

So take a trip back to your early life and think about when and how the good girl in you began to emerge. You may remember how wonderful it fell before you had to put on the muzzle.

THE GOOD GIRL GOES TO COLLEGE

For some girls, college is the time to try to break out of the good-girl mold. And yet by then the message is pretty ingrained in many of us and there may be a reluctance to challenge the “system.” or at the very least an inability in knowing how to begin. Dr. Gathron says that as part of her research on women and self-esteem, she asks freshmen women to tell her what they think and feel about themselves, using adjectives and descriptors. The results are the same from year to year. “What is so amazing is that they sit and ponder,” she says. “They have a hard time coming up with anything. As women, we're told all our lives how to act and what's expected of us. We haven't thought enough about ourselves and what we feel and think.”

As a member of the first coed graduating class of Union College. I found myself the first year in a class with twenty men and only one other woman, and through the entire semester the professor never once made eye contact with either of us. On Halloween we wore matching pumpkin outfits with green hoods over our faces, just to see if we could get a rise out of him, but even that didn't do the trick.

THE GOOD GIRL GETS A JOB

By the time you enter the work force, you've had over twenty years of good-girl training—and you really know your stuff. With so much reinforcement, it makes perfect sense that you would follow the good-girl principles in your job—and at first glance, it actually seems to work. Because they may have a vested interest in keeping you in your place, some bosses and most of your co-workers will praise you for your good behavior. You'll be complimented for following the rules, being patient, doing the lion's share of work, and not taking any stupid risks. I just loved the line that the New York Times wrote in a short bio of Justice Ruth Ginsburg after the approval of her nomination to the Supreme Court: “She handled her intelligence gracefully—sharing her schoolwork, avoiding the first-person singular and talking often of having been in the right place at the right time.” It was as if the Times was saying, ”See? It pays to be a good girl. Women should put everybody else ahead of themselves and attribute all of their success to luck.”

But despite what the “evidence” appears to indicate, the kind of good-girl behavior that won you praise at home and A's in school ultimately won't advance your career. Why not? Because the standards have changed.

“There are no daily quizzes in the world of work.” say the Sadkers. “This is where boys learn the value of having developed that public voice, the one girls are discouraged from using in school.”

Career success isn't about learning the textbook answers to questions and repeating them back on a test. It's about generating fresh, creative ideas that make people go “Wow.” It's not about waiting to be called on. It's about asking for what you want. It's not about making everyone like you. It's about getting things done effectively even if you have to ruffle some feathers—or kick some butt.

That's not to say that being a good girl will prevent you from earning any points in your job. As a good girl you might make a reliable manager—because you take care of your charges, follow rules, and work your tail off. But that's never going to make you a star.

Okay, sometimes the gods smile down on good girls and reward them for their hard work. But for the most part, good-girl traits will sabotage your chances for gaining a key leadership position.

Robin Dee Post is a clinical psychologist in Denver who has worked with many career women in therapy and believes there are two distinct ways women sometimes sabotage their success, and also create unnecessary stress for themselves.

The first involves relationships at work—how we respond to bosses, co-workers, and subordinates.

“Because we've been trained to be nice and always think of others, it makes it harder for us to put our own needs first in the work place,” Post says. “As a result we have trouble confronting others when we have a problem with them. This same factor also makes us reluctant to let others know of our accomplishments.”

The second way involves putting excessive demands on ourselves—due perhaps to excessively high demands or criticism when we were growing up. That, Post believes, leads to perfectionism, procrastination, and an overcommitment to work.

HOW MUCH OF A GOOD GIRL ARE YOU?

By now you may feel that you already have an idea of your own specific good-girl patterns, but trust me, it's trickier than you might expect. Sometimes, when you think you're performing at your best, the good girl in you is actually busy undermining your efforts. Here's a lesson from my own life.

It happened the summer I was thirty-one, working as the articles editor at Family Weekly magazine, which was a Sunday newspaper supplement similar to Parade and was later purchased by USA Today. My job appeared to be pretty stable, until, that is, the day the editor-in-chief unexpectedly resigned to become editor of GQ magazine. I'd just put the finishing touches on plans for a three-week adventure cruise around northern Greenland and the news made me feel as if I had just been rammed by an iceberg. Would he take me with him? I wondered. If not, how would things change for me at the magazine? Was my job in jeopardy? Two days after my boss's announcement, I was called into the publisher's office and informed, much to my surprise, that I would be in charge of running the magazine while a search was conducted for a new editor-in-chief. And here was the icing on the cake: my name was being added to the list of candidates for this job.

As I left the publisher's office, there was one immediate thought flashing through my mind: Well, I guess I'm not going to get to see any puffins or polar bears this year. But once the news sank in, I was exhilarated, and I felt a burning passion to put my stamp on the magazine during my stint as acting editor. I also realized that I really, really wanted the job. The publisher had told me that like all the other candidates, I had to submit a long-term proposal for the magazine to the top people in the company. I vowed that when the big guys were done reading mine they'd have to collect their socks from across the room.

Over the next weeks—and what turned out to be months—I threw myself into the job, doing everything possible to make the magazine snazzy and get it to the plant on time each week. The publisher had asked that I send him memos on upcoming cover stories, but other than that he left me to my own devices. I didn't make any attempt to contact him, figuring it was best to leave well enough alone. My proposal for the magazine was completed in two weeks and I sent it by interoffice mail to top management, keeping my fingers crossed.

There were a few hairy moments, mainly with the staff: morale got very low because it was taking management so long to make a decision, but I was as pleasant as could be, bending over backwards to get people to like me. My biggest headache was with the senior editor, who called me into her office one day, told me to shut the door, and announced that she had the publisher wrapped around her finger and could make or break my chances for the job. I suggested we have dinner and talk over the situation.

Finally, after three long months, the publisher phoned and asked me to join him the next day for lunch at the Palm, a famous New York steak house favored by middle-aged salesmen with arteries, as hard as curtain rods. I knew I was about to learn my fate, and something told me that the news wasn't good: the job was probably going to someone else and I was about to get surf-and-turf as a consolation prize.

Twenty minutes after we sat down, the publisher still hadn't mentioned my job, though he'd twice called me “Princess,” which I took as a sign that a power position probably wasn't in my immediate future. The biggest omen occurred when I returned from the ladies’ room. Not wanting to seem like a sissy, I'd asked him to order me a glass of red wine while I was gone. “Bad news,” he announced as I sat down again. “They won't bring your wine until they see a picture ID.”

Over coffee I learned that indeed I wasn't going to be editor-in-chief. The guy they'd hired was about twelve years older than I, with “lots of experience.” They gave me a title change and a raise and I got some consolation from the fact that my proposal was supposedly the best of the lot. What I told myself through my disappointment was that I'd lost out because I was too young. I believed that my day would come and that years later I would look back and realize that everything had worked out for the best.

It's only now, over ten years later, while writing this book, that the truth has finally hit me: I failed to get the job of editor-in-chief not because I was too young at the time but because I'd been a good girl. I'd retreated into the woodwork, rationalizing that a low profile would help my case. I'd tried so hard to make the staff like me that they viewed me as desperate and thus, powerless. And I'd never taken any steps to demonstrate to top management that I had a burning passion for the position.

What I should have done during my months as acting editor was work closely with the publisher and allow him to see what a capable editor I was. I should have been more of a boss to the staff, showing them that I wouldn't tolerate insubordination or whining. And I should have asked top management for the opportunity to present my proposal in person and then convince them that I was the one for the job.

Sure, things ultimately worked out very well for me, but who knows what opportunities might have unfolded if I'd gotten the top job at such a young age.

Recognizing how much I acted like a good girl during that time has been a turning point for me. It's allowed me to see that good-girl behavior often masquerades as something we consider to be positive. You tell yourself, for instance, that you're cautious or modest or patient, and you assume that's the mark of a real pro. Yes, sometimes caution and modesty and patience have their place. But left unchecked, they are career quicksand.

So when you're considering how much of a good girl you may be, look below the surface. If you're not certain how ingrained your good-girlism is, the quiz below will give you some clues.

THE OFFICIAL GOOD-GIRL QUIZ

1) Your boss calls a meeting and announces to you and the rest of the staff that he wants each of you to come up with suggestions for a presentation geared to winning new clients. He offers several guidelines, based on what's worked for clients in the past. You

a. put together a thoughtful, well-written plan, following his instructions to the T.

b. come up with a plan that's outside the parameters your boss suggests—in fact, it's partially inspired by something you saw on MTV—but you sense it could work beautifully, so you submit it anyway.

2) You've recently been put in charge of a new area in your company and you've spent several weeks researching and developing a set of goals for the area. Two of your new employees want you to add several of their pet interests to your list. You

a. hear them out but decide not to incorporate their ideas into your overall plan because they don't fit with your mission.

b. include their goals because you know it's important to make them feel part of the team.

3) Your boss asks you to provide her with written suggestions on how to improve some of the services your company provides. She says she wants it in two weeks. When the date arrives, you

a. give yourself a few extra days to polish your report, counting on the fact that your boss will appreciate your efforts.

b. hand in the report, knowing that though it's good, you would have loved to have had another week.

4) Your secretary arrives late for the fifth time in two weeks. She has mentioned to you that she is having problems with both her boyfriend and her sinuses. You

a. call her into your office and explain that you want her at her desk promptly at nine each morning.

b. say nothing, because she's basically responsible and you can count on her to sort things out. Scolding her will only make things worse.

5) At a meeting of your department, you bring up an idea you've been cogitating on for a few weeks. Your boss seems mildly curious and she throws it out for discussion. A few colleagues mumble polite encouragement, but one co-worker, someone you consider a real pal, announces that she doesn't feel the idea has much merit. She backs up her opinion with several statistics. You feel

a. embarrassed and hurt.

b. curious about how she knows so much on that particular subject.

6) One of your clients sends you a terrific note praising your performance. You

a. Pass along the letter to your boss with a note that says, FYI.

b. Tuck it in a file you keep of letters and notes like this, just in case you might want to use it in the future.

7) In the past year you've taken on more and more of your boss's responsibility, allowing him to assume more exciting projects himself. Your boss has consistently praised your performance and announced the other day that if it weren't for the budget freeze, he'd promote you. You

a. trust your boss to come through when he has the money.

b. make an appointment to see your boss and say that you'd like him to consider giving you a new title, with a raise to follow when he has the money.

8) You hear through the office grapevine that a colleague has called an important resource of yours, ostensibly just to checkout a lead. You

a. step into your colleague's office and say that you expect him to check with you before he contacts a source that you have cultivated.

b. bide your time, deciding that you will challenge him, but when you have actual evidence that he's been poaching on your territory.

9) On two separate occasions you find several of the people who work for you whispering behind partially closed doors. After asking yourself if something could be up, you

a. tell yourself you're being paranoid.

b. tell yourself something is definitely brewing and try to find out what it is.

10) You accept a new job that you sound perfectly suited for. Three weeks after starting, however, you realize that you've got far more to learn than you realized. As you lie in bed at night you think

a. I can do this, I can do this.

b. Oh, no. I'm in over my head.

SCORING YOURSELF

Give yourself 1 point for every b answer to questions 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9, and none for a answers to those questions. Give yourself one point for every a answer for questions 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10, and none for b answers to those questions.

If you scored 9 or 10 points, you're gutsy as hell, and I'm tempted to say give this book to a more needy friend. But since the title of the book intrigued you, there's a chance a good girl is lurking inside, and you may need reinforcement on your gutsiness (or some of your answers may have reflected how you would like to behave rather than how you generally do).

If you scored between 5 and 8, you've already developed some gutsy instincts, but you've got much more to learn.

If you scored under 5, your good-girlism is pretty seriously ingrained. You need help, but trust me, there's hope.

NO, YOU ABSOLUTELY DO NOT HAVE TO ACT LIKE A MAN

As I've talked about some of the ways gutsy girls do business, you may have begun to wonder whether acting gutsy really comes down to acting like a man.

That, after all, was the advice offered to women when they first poured into the workforce in the seventies. You may have read or at least heard of the mega best-selling book Games Mother Never Taught You by Betty Harragan. It burst on the scene in 1977, advising women that the key to making it in a man's world was to use the militaristic thinking and team-sport strategies that had worked so successfully for men. Much of the advice that appeared in the years afterwards stressed similar principles.

The trouble with that approach, as so many of us discovered Women don't feel comfortable acting or dressing like men. “When a woman tries to behave like a man,” says Barbara Berg, “she feels phony and alienated—even amputated.”

Gutsiness, to me, doesn't mean acting tough or macho or using phrases like “Let's hit ‘em where it hurts” or “Are they ready to play ball yet?” (though if you feel like it, by all means go ahead) It means trusting your instincts, going after what you want, and not being worried about what other people will think—in other words rediscovering the original gumption you felt at ten or eleven, before people did their best to derail it.

Acting like men did seem to pay off for some of the women who were in the vanguard of successful career women. Many of them probably felt it was a necessity, so they didn't seem like alien creatures. But I think a couple of factors have greatly diluted the necessity for being one of the guys. First, there's less of an emphasis in business these days on the military model. The buzzwords (and who knows if the gurus will be talking this way in ten years) are team work, empowerment, sharing the wealth. Also, as more women in higher positions have dared to act like women rather than men, it's made it far easier for the next generation of women to go in there and be themselves. New York Times reporter Maureen Dowd said in a speech last year that more and more professional women are discovering the “inner girl” and are not afraid to reveal her at the office.

That said, there's a helluva lot (excuse the macho talk) to be learned from men. I don't mean all men. Interestingly, there are plenty of guys who are good girls (someone wrote not long ago that At Gore might be “too good” to be President, too much of a pleaser), and they end up stuck in middle-management jobs for decades.

The ones you should pay attention to are the gutsy ones. Watch them talk, plan, move into action. I'm not suggesting you imitate exactly how they get what they want. Rather, simply be inspired by how they trust their instincts and do what they think is best.

Sometimes being gutsy is actually a matter of taking a good-girl tendency and restructuring it just a little. Good girls, for instance, worry a lot about pleasing people, often sacrificing their own needs in the process. But pleasing the right people in the right way is one of the best skills in business. When IBM announced that it was consolidating all its advertising under the Ogilvy and Mather Agency, the Wall Street Journal attributed the mega-coup to the agency's North American operations president Rochelle Lazarus, who sources indicated was brilliant at making “a client feel understood.”

THE TRUE SECRET OF BEING A GUTSY GIRL

This book is filled with strategies on how to uncover your natural gumption and be a gutsy girl. You may be wondering how you can possibly incorporate so many changes into the way you handle yourself. Keep this in mind: There's a wonderful dynamic at work when it comes to gutsiness. As soon as you try just one little gutsy thing, you will find it so effective and intoxicating you will be eager to try another. It is the M&M's approach to self-improvement.

Marjorie Lapp, a psychotherapist in Walnut Creek, California, who treats many women with classic good-girl tendencies, says she's found that they start out feeling very reluctant to try something new or adventurous because they worry that there will be dire consequences. “But when they do finally make a move, they discover that instead of something bad happening, it is often something very good,” she said. “And that realization is totally liberating.”

The fact is that unlike at home and in school, your gutsy efforts will sooner or later be rewarded.

A friend of mine, Mary Jo Sherman, who is president of Levit and Sherman advertising agency, puts it this way: “When you're growing up and you don't act like a good girl, your mother sends you to your room. But at work, being gutsier wins you a major client or some other kind of prize. As you see what it nets you, you become braver and braver.”

Let's start with the very first strategy of a gutsy girl.

[/lyrics]

DETAILS

TITLE: Why Good Girls Don't Get Ahead _But Gutsy Girls Do _Nine Secrets Every Career Woman Must Know - Kate White - 9780446518277

Author:

Language: English

ISBN:

Format: TXT, EPUB, MOBI

DRM-free: Without Any Restriction

SHARE LINKS

Mediafire (recommended)Rapidshare

Megaupload

No comments:

Post a Comment