[/caption]

[/caption]DESCRIPTION

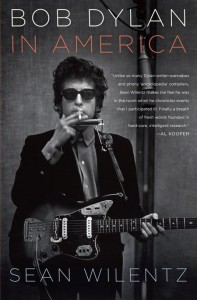

One of America’s finest historians shows us how Bob Dylan, one of the country’s greatest and most enduring artists, still surprises and moves us after all these years.Growing up in Greenwich Village, Sean Wilentz discovered the music of Bob Dylan as a young teenager; almost half a century later, he revisits Dylan’s work with the skills of an eminent American historian as well as the passion of a fan. Drawn in part from Wilentz’s essays as “historian in residence” of Dylan’s official website, Bob Dylan in America is a unique blend of fact, interpretation, and affinity—a book that, much like its subject, shifts gears and changes shape as the occasion warrants.

Beginning with his explosion onto the scene in 1961, this book follows Dylan as he continues to develop a body of musical and literary work unique in our cultural history. Wilentz’s approach places Dylan’s music in the context of its time, including the early influences of Popular Front ideology and Beat aesthetics, and offers a larger critical appreciation of Dylan as both a song writer and performer down to the present. Wilentz has had unprecedented access to studio tapes, recording notes, rare photographs, and other materials, all of which allow him to tell Dylan’s story and that of such masterpieces as Blonde on Blonde with an unprecedented authenticity and richness.

Bob Dylan in America—groundbreaking, comprehensive, totally absorbing—is the result of an author and a subject brilliantly met.

REVIEWS

"Among those who write regularly about Dylan, Wilentz possesses the rare virtues of modesty, nuance, and lucidity, and for that he should be celebrated and treasured....Wilentz is very, very good on the actual music. In fact, the centerpiece of his book is a vivid look at the 'Blonde on Blonde' sessions, during which the musicians teased and groped their way toward the album's 'thin, wild mercury sound,' in Dylan's famous description."—Bruce Handy in _The New York Times Book Review_"In this often revelatory new study, Wilentz locates Dylan's work in the context of some surprising influences....The greatest gift for Dylan fans, however, is Wilentz's detailed account of the making of 1966's 'Blonde on Blonde'....Unless Dylan himself writes about it in the fabled Chronicles: Volume Two, this is the definitive word on the creation of his greatest album."—Andy Green in Rolling Stone

"_Bob Dylan in America,_ a new biography of the singer-songwriter by distinguished cultural [and] political historian Sean Wilentz, gives an enjoyably thorough, convincing explanation of why Dylan's new music has gone on finding new audiences ever since he burst upon the New York folk scene of the early 1960s, fresh from the iron range of northern Minnesorta and ferociously ambitious for his art. It's an extraordinary, resonant intersection of subject and biographer....Where Wilentz excels is in teasing out the origins of Dylan's artistic impulses, the context in which they arose and flowered, the multiple sources of his art."—Tim Rutten in _The Los Angeles Times_

"Another book about Bob Dylan! Is there any more to be said? The answer is, of course, yes, and who better to say it than Sean Wilentz, a Princeton professor of American history?...What this book finally does -- this is me, not Wilentz -- is establish Dylan as the 20th century's Walt Whitman. Like Whitman he sings the songs of America in the conviction that they can be said in no other way. And, like Whitman, he commits himself to travelling the roads of America, looking and remembering. From the shelves full of Dylan books this and one other -- Christopher Ricks's Dylan's Visions of Sin -- are the ones to read. This is also one to look at: the pictures are cunningly well chosen."—Bryan Appleyard in _The Sunday Times (UK)

_

"Like many a quirkily brilliant music critic...Mr. Wilentz chooses pet aspects of his subject's career and then invests them with the requisite importance....Mr. Wilentz's vast knowledge of Dylan performances touchingly conveys his nearly lifelong reverence for his subject."—Janet Maslin in _The New York Times_

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR BOB DYLAN IN AMERICA

"A panoramic vision of Bob Dylan, his music, his shifting place in American culture, from multiple angles. In fact, reading Sean Wilentz’ Bob Dylan in America is as thrilling and surprising as listening to a great Dylan song."

—Martin Scorsese

"All the American connections that Wilentz draws to explain the appearance of Dylan’s music are fascinating, particularly at the outset the connection to Aaron Copland. The writing is strong, the thinking is strong – the book is dense and strong everywhere you look."

—Philip Roth

"Unlike so many Dylan-writer-wannabes and phony ‘encyclopedia’ compilers, Sean Wilentz makes me feel he was in the room when he chronicles events that I participated in. Finally a breath of fresh words founded in hardcore, intelligent research."

—Al Kooper

"This should have been impossible. Writing about Bob Dylan's music, and fitting it into the great crazy quilt of American culture, Sean Wilentz sews a whole new critical fabric, part history, part close analysis, and all heart. What he writes, as well as anyone ever has, helps us enlarge Dylan's music by reckoning its roots, its influences, its allusive spiritual contours. This isn't Cliff Notes or footnotes or any kind of academic exercise. It's not a critic chinning on the high bar. It's one artist meeting another, kickstarting a dazzling conversation."

—Jay Cocks, screenwriter for THE AGE OF INNOCENCE and THE GANGS OF NEW YORK

"Sean Wilentz is one of the few great American historians. His political and social histories of American Democracy are masterful and magisterial. In this work, he turns his attention to the artistic genius of Bob Dylan – and the result is a masterpiece of cultural history that tells us much about who we have been and who we are."

—Cornel West, Class of 1943 University Professor in the Center for African American Studies at Princeton University

"Sean Wilentz makes us think about Bob Dylan’s half-century of work in new ways. Combining a scholar’s depth with a sense of mischief appropriate to the subject, Wilentz hears new associations in famous songs and sends us back to listen to Dylan’s less familiar music with fresh insights. By focusing on the parts of Dylan’s canon that most move him, Wilentz gets

straight to the heart of the matter. If you thought there was nothing new to say about Bob Dylan’s impact on America, this book will make you think twice."

—Bill Flanagan, author of A&R and EVENING’S EMPIRE and Editorial Director, MTV Networks.

"Sean Wilentz’s beautiful book sets a new standard for the cultural history of popular music in America. He loves the music and he loves America, but his loves do not blind him, they open his eyes. In Wilentz’s erudite and lively account, Dylan’s music, and folk music, and rock music, are all indelibly woven into the whole story of an entire country. This book is chocked with new contexts for old pleasures. There are surprises and illuminations on almost every page. A great historian has written a history of the culture that formed him. Like Dylan, Wilentz is a deep and probing American voice. Bob Dylan’s America is Bob Dylan’s good luck, and ours. It is an extraordinary affirmation of singing and strumming and feeling and learning and believing."

—Leon Wieseltier

PREVIEW

[lyrics]INTRODTION

For thirty years I have tried to write about American history, especially the history of American politics. It is extremely hard work, but gratifying over the long haul. Writing historical pieces about American music and about Bob Dylan wouldn’t have been in the cards but for a fluke, the result of strange good fortune dating back to my childhood.

While I was growing up in Brooklyn Heights, my family ran the 8th Street Bookshop in Greenwich Village, a place that helped nurture the Beat poets of the 1950s and the folk revivalists of the early 1960s. My father, Elias Wilentz, edited The Beat Scene, one of the earliest anthologies of Beat poetry. Down from the shop, on MacDougal Street, was an epicenter of the folk-music explosion, the Folklore Center, run by my father’s friend Israel Young, whom everyone called Izzy, an outsized enthusiast with an impish grin and a heavy Bronx-Jewish accent. Nothing in that setting was anything I had sought out, or had any idea was going to become important. As things turned out, I was just lucky.

On occasional pleasant Sundays, we’d take family strolls that almost always included a stop at the Folklore Center, which was crowded wall to wall with records and stringed instruments and had a little room in the back where musicians hung out. My first memories of Bob Dylan, or at least of hearing his name, are from there—Izzy and my dad would talk about what was happening on the street, and I (a son who wanted to look and act like his father) would eavesdrop. Only much later did I learn that Dylan first met Allen Ginsberg, late in 1963, in my uncle’s apartment above the bookshop.

A few buildings north of Izzy’s store, next to the Kettle of Fish bar, a staircase led down into a basement club, where Dylan acquired what it took to make himself a star. The Gaslight Cafe, at 116 MacDougal, was the focal point of a block-long spectacle of hangouts and showcases, including the Café Wha? (where Dylan played his first shows in the winter of 1961). Down adjoining tiny Minetta Lane, around the bend on Minetta Street, there was another coffeehouse, the Commons, later known as the Fat Black Pussycat. These places, along with the Bitter End and Mills Tavern on far more touristy Bleecker Street, and Gerde’s Folk City on West Fourth Street, were Bob Dylan’s Yale College and his Harvard.

The neighborhood had a distinguished bohemian pedigree. A century before, over on the corner of Bleecker and Broadway, Walt Whitman loafed in a beer cellar called Pfaff’s, safe from the gibing mainstream critics, whom he called “hooters.” A little earlier, a few blocks up MacDougal in a long-gone house on Waverly Place, Anne Charlotte Lynch ran a literary salon that hosted Herman Melville and Margaret Fuller, and where a neighbor, Edgar Allan Poe, first read to an audience his poem “The Raven.” Eugene O’Neill, Edna St. Vincent Millay, e. e. cummings, Maxwell Bodenheim, and Joe Gould, among others, were twentieth-century habitués of MacDougal Street.

When Dylan arrived in the Village, the Gaslight was the premier MacDougal Street venue for folksingers and stand-up comics. Opened at the end of the 1950s as a Beat poets’ café—for which it received a curious write-up in the New York Daily News, then the quintessential reactionary city tabloid—the Gaslight proclaimed itself, carnival-style, as “world famous for the best entertainment in the Village.” Unlike many of the other clubs, it was not a so-called basket house, where walk-on performers of widely ranging competence earned only what they managed to collect in a basket they passed around the audience. The Gaslight was an elite spot where talent certified by Dave Van Ronk and other insiders, as many as six performers a night, received regular pay.

Not that the place was fancy in any way. Pine paneled (until its owners stripped it down to its brick walls) and faintly illuminated by fake Tiffany (or, as Van Ronk called them, “Tiffanoid”) lamps, the Gaslight had leaky pipes that dripped on what passed for a stage, no liquor license (that’s what brown paper bags and the Kettle of Fish were for), a tolerable sound system, and hardly any room. If one used a crowbar and a mallet, it might have been possible to jimmy a hundred people in there. The threat of a police raid—for noisiness, or overcrowding, or refusing to play along and pay off the Mob—was constant. But on MacDougal Street, playing the Gaslight was like playing Carnegie Hall.

Van Ronk was the king of the hill among the Gaslight’s folksingers; the emcee was Noel Stookey (who became the Paul of Peter, Paul, and Mary); and the headliners included Tom Paxton, Len Chandler, Hugh Romney (better known as the late-1960s psychedelic prankster and communalist Wavy Gravy), and young comics like Bill Cosby and Woody Allen. When Dylan, with Van Ronk’s imprimatur, cracked the Gaslight’s prestigious performers’ circle in 1961, he secured sixty dollars a week, which gave him enough to afford the rent on a Fourth Street apartment—and took a big step toward real fame and fortune. “It was a club I wanted to play, needed to,” Dylan recalls in his memoir, Chronicles: Volume One.

A remarkable tape survives of what appears to have been a splicing together of two of Dylan’s Gaslight performances, recorded in October 1962, in accord with what then qualified as professional recording standards. (Widely circulated for many years as a bootleg, the tape was eventually released in abbreviated form in 2005 as a limited-edition compact disc, Live at the Gaslight 1962.) The singer may have left his harmonica rack at home; in any case, this is one of the few early recordings where he performs for an audience without his harmonicas. But for all of its unpretentious, even impromptu qualities, the tape reveals how greatly and rapidly Dylan’s creativity was growing.

A year earlier, Van Ronk’s first wife, Terri Thal, had recorded Dylan, also at the Gaslight but with far inferior equipment, in an attempt to persuade club owners in nearby cities to hire the young singer. (Thal reports that someone stole the tape; it has long been available as a vinyl LP and on compact disc, known to collectors as “The First Gaslight Tape.”) As a business scheme, the recording flopped, even though it included the best of Dylan’s first songs, “Song to Woody.” A year later, though, Dylan had jumped to the level of composing “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”—a song the world beyond the Village and the folk revival would not hear until its release more than six months later on Dylan’s second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. It might be the ghostly singing along by the audience on “Hard Rain,” or it could just be the benefits of hindsight, but this second Gaslight tape vibrates with a sensation that Bob Dylan was turning into something very different from what anyone had ever heard, an artist whose imagination stretched far beyond those of even the most accomplished folk-song writers of the day.

I first heard Dylan perform two years after that—at Philharmonic Hall, not the Gaslight. It was another bit of luck: my father got hold of a pair of free tickets. And even though I was only thirteen, I’d been made acutely aware of Dylan’s work. A slightly older friend had presented Freewheelin’ to a little knot of kids in my (liberal, Unitarian) church group as if it were a piece of just-revealed scripture. I didn’t understand half of the album; mostly, I was fixed on its sleeve cover, with its now famous photograph of Dylan, shoulders hunched against the cold, arm in arm with a gorgeous girl, walking on Jones Street—a picture that, with its hip sexiness, was more arousing than anything I’d glimpsed in furtive schoolboy copies of Playboy.

Some of what I did understand in the songs was funny, some of it was uplifting, and a lot of it was frightening: the line “I saw a black branch with blood that kept drippin’ ” from “Hard Rain” stood out as particularly chilling. But I loved the music and Dylan’s sound, the guitar, the harmonica, and a voice that I never thought especially raspy or grating, just plain. Getting the chance to see him in concert was a treat, about which I have more to say below. In time, it proved to be a source of even greater luck.

The next turn in the story, almost forty years later, is more mysterious to me. After a long and deep attachment through high school, college, and after, my interest in Dylan’s work began to wane about the time Infidels appeared in 1983. Although his religious turn was perplexing, even off-putting, the early gospel recordings at the end of the 1970s and beginning of the 1980s had also, I thought, been gripping, taking an old American spiritual tradition, already updated by groups such as the Staple Singers, and recharging it with full-blast rock and roll. Dylan had seemed to be doing to “Precious Lord” what he once had done to “Pretty Polly” and “Penny’s Farm.” Now, though, except for a few cuts on Infidels and on Oh Mercy six years later, his music sounded to me tired and torn, as if mired in a set of convictions that, lacking deeper faith, were substituting for art.

I came back to Dylan’s music in the early 1990s when he released a couple of solo acoustic albums of traditional ballads and folk tunes, sung in a now-aging, melancholy voice, yet with some of the same sonic sensations I remembered from the early records. The critic Greil Marcus (who, several years later, became my friend and collaborator) has written that with these recordings, Dylan began retrieving his own artistic core—but I had more personal reasons for admiring them with a special intensity. When my father fell mortally ill in 1994, hearing Dylan’s hushed, breathy rendition on the second of the albums, World Gone Wrong, of the 1830s-vintage hymn “Lone Pilgrim” brought me tears and consolation I wouldn’t have gone looking for in any church or synagogue.

By now I was writing about the arts as well as about history. On a lark, in 1998, I wrote an article for the political magazine Dissent about Marcus’s Dylan book, Invisible Republic, and Dylan’s latest release, Time Out of Mind, all prompted by a Dylan show I attended, goaded by a clairvoyant friend, the previous summer at Wolf Trap in Virginia. In 2001 a phone call came out of the blue from Dylan’s office in New York asking if I would like to write something about a forthcoming album, called “Love and Theft,” for Dylan’s official Web site, www.bobdylan.com. Once I’d established it wasn’t somebody playing a practical joke, I agreed, provided that I liked the album, which in the end I very much did. I wrote more for the Web site over the following months and invented the somewhat facetious title of the site’s “historian-in-residence,” a job nobody else seemed to be angling for, at a home office suspended in cyberspace.

Sometime in 2003, plans took shape for an official release, as part of a retrospective series, of the tape made on that long-ago night when I first heard Bob Dylan in concert. When called upon to write the liner notes for what would become The Bootleg Series, Vol. 6: Bob Dylan Live 1964, Concert at Philharmonic Hall, I found the assignment intimidating. Dylan has always managed to land truly fine writers and experts, including Johnny Cash, Allen Ginsberg, Tony Glover, Pete Hamill, Nat Hentoff, Greil Marcus, and Tom Piazza, when he hasn’t written the liner notes himself. I also worried about what it would be like trying to describe a scene from so long ago without sounding either coy or pedantic. How much would I even remember?

The memory part turned out to be easy. Listening to the recording brought back in a rush the feel of the occasion—the evening’s warmth; the golden glow of the still-new Philharmonic Hall in the still-under-construction Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts; the sometimes giddy rapport that Dylan had with the audience (unimaginable in today’s arena rock concerts). But as a historian, I also felt a responsibility to fill in the larger context: what the world was going through and what Dylan was up to in the autumn of 1964. The murders of three civil-rights workers in Mississippi, the first signs that America would escalate its involvement in Vietnam, the successful test of an atomic weapon by Communist China, had all marked the beginning of a scarier phase in national and world affairs. Dylan, meanwhile, had been moving away from the fixed moral position of his earlier work into a more personal and impressionistic vein, and would soon return, though in wholly new ways, to the electrified music that had been his first love as a teenager.

I tried to braid the background together with my memories, hoping to recapture the sense of what it was like to see things through thirteen-year-old eyes (and say it with a bit of a thirteen-year-old’s voice) while sustaining what authority I had as a professional historian who by now was more than twice as old as Bob Dylan was that night. I tried to evoke the feeling of being a teenage cultural insider, self-consciously nestled as close to the center of hipness as possible, with an edge of callow smugness and little awareness of my own good fortune. Maybe half of us in the audience had worked an honest day in our lives, and few had come close to getting our skulls cracked defying Jim Crow. But we thought we were advanced and special, and for us the concert was partly an act of collective self-ratification. I wanted my notes to evoke the joy as well as the folly of that youthful New York moment.

The notes were eventually nominated for a Grammy Award, which was another kind of ratification, although the idea of middle-aged folly occurred to me as well. The attention that the nomination received surprised me. The recording industry’s manufacture of spectacle had become so grand that even the low-priority Best Album Notes category got newspaper play. I tried not to kid myself too much about the hoopla: an Ivy League history professor getting picked to go to Los Angeles along with Usher and Green Day and Alicia Keys is an obvious “man bites dog” filler story. I did, though, take pride in how what I wrote interested people well outside my usual circles. As awards day closed in, I began to get that self-consciously hip feeling back again: going to the Grammys was pretty exciting. By the time I arrived in Los Angeles, I badly wanted to win.

I didn’t. It hurt when the presenter read someone else’s name, and I couldn’t hide it. From the row in front of mine, an elegantly dressed woman, older than I, noticed my dejection and extended her hand.

“Don’t you worry, honey, I didn’t win myself, and ain’t it great being here?” I kissed her hand, suddenly feeling better, grateful to be welcomed, if only for a weekend, into the ranks of hardworking musicians and artists.

I returned to writing my history books and teaching my history classes, but also continued to write an occasional essay and deliver an occasional lecture on aspects of American music, including Dylan’s work. In 2004, with Greil Marcus, I co-edited The Rose and the Briar, an anthology of essays, short stories, poetry, and cartoons based on various American ballads, to which I contributed an essay on the old blues song “Delia,” performed by Dylan on World Gone Wrong. Then, three years after losing the Grammy, with another history book done, I began thinking about attempting a more ambitious piece of music writing, a coherent commentary on Dylan’s development as well as his achievements, and on his connections to enduring currents in American history and culture.

To be sure, my essays had skipped over a lot, ignoring almost completely the years from 1966 to 1992—a quarter century in which, according to the not entirely ironic announcement by Al Santos, Dylan’s stage manager, that precedes every live show, Dylan “disappeared into a haze of substance abuse [and] emerged to find Jesus” before he “suddenly shifted gears, releasing some of the strongest music of his career beginning in the late nineties.” All that made sense to me, and I thought that the years I had covered in my essays coincidentally had brought Dylan’s most concentrated periods of powerful creativity, including the most powerful of all, between 1964 and 1966. Without quite realizing it, I had written about some of the high points of two of the major phases in Dylan’s career—reason enough, I told myself, to see what they might look like assembled between two covers, revised as the chapters of a much longer book. I had also written about certain musical genres and figures to whom Dylan himself had alluded, if only tacitly, as personal influences, ranging from the shape-note choral music in the nineteenth-century Sacred Harp tradition to the leftist-influenced orchestral Americana of Aaron Copland. These pieces were no more comprehensive in their coverage than my essays on Dylan were. But they hinted at some connections I wanted to make between Dylan’s work and American history and culture.

There is plenty of fascinating commentary on Dylan’s songs, and there are several informative biographies. But even the best of these books do not contain all of what I have wanted to know about Dylan’s music and the strains in American life that have provoked and informed it. I have never been interested in simply tracking down, listing, and analyzing the songs and recordings that influenced Dylan, important though this task is to understanding his work. I have instead been curious about when, how, and why Dylan picked up on certain forerunners, as well as certain of his own contemporaries; about the milieu in which those influences lived and labored and how they had evolved; and about how Dylan, ever evolving himself, finally combined and transformed their work. What do those tangled influences tell us about America? What do they tell us about Bob Dylan? What does America tell us about Bob Dylan—and what does Dylan’s work tell us about America? These are the questions that finally pushed me to write this book.

While I was preparing to write about “Love and Theft” in late summer 2001, I thought I perceived (and it turned out to be a pretty obvious observation) that the album was a kind of minstrel show, in which Dylan had assembled bits and pieces of older American music and literature (and not just American music and literature) and recombined them in his own way. The musical reconstructions appeared to be rooted in what Pete Seeger has called “the folk process,” and in Dylan’s lifelong practice of transforming words and melodies for his own use. But they also now appeared to be more sophisticated, self-conscious, and elusive as well as allusive, drawing upon sources from well outside the folk mainstream (ranging from Virgil’s Aeneid to mainstream pop tunes from the 1920s and 1930s), as well as from classic blues recordings by Charley Patton and the Mississippi Sheiks. I came to see it as an urbane if, to some, problematic twist in Dylan’s art, the latest of his reshapings of old American musical traditions shared by the minstrels, songsters, and vaudevillians, as well as the folk and blues singers. I called his reshapings of those traditions modern minstrelsy.

I originally imagined writing a book that would build on my essay about “Love and Theft” and examine how older forms of adaptation prepared the way for Dylan the modern minstrel—but I quickly scrapped that idea. For one thing, as interesting as his later endeavors have been, I think that Dylan completed by far his strongest work, mixing tradition and utter originality, in the mid-1960s and mid-1970s, a judgment he himself appears to share.* A narrative that even appeared to climb ever upward toward Dylan’s fully mature output would be nonsense. For another thing, Dylan’s career has been an unsteady pilgrimage, passing through deep troughs as well as high points, including a prolonged period in the 1980s when, again by his own admission, his work seemed to be spinning in circles. Any account of Dylan’s cultural importance must be built out of his ups and downs, zigs and zags, and relate how he has carried his art from one phase to another. Finally, although Dylan has long been a constant innovator—or, as the Irish troubadour Liam Clancy once called him, a “shape-changer”—his work has also exhibited strong continuities. Dylan has never stuck to one style for too long, but neither has he forgotten or forsaken or wasted anything he has ever learned. Anyone interested in appreciating Dylan’s body of work must face the challenge of owning its paradoxical and unstable combination of tradition and defiance.

I decided instead to examine some of the more important early influences on Dylan and then focus on Dylan’s work from the 1960s to the present at certain important junctures. The opening chapters might seem to have little to do with Dylan, especially in their early sections, as they trace the origins and cultural importance of influential people or currents, but they do in time bring Dylan into the story, and show how he connected with the forerunners, sometimes directly, sometimes not. A chapter about Dylan’s song “Blind Willie McTell,” as well as chapters about “Delia” and another song from World Gone Wrong, “Lone Pilgrim,” also require extended passages explaining important background material. I ask for the reader’s indulgence to hang on during all of these chapters, assured that the connections to Bob Dylan will be revealed soon enough. The remaining chapters deal more directly with Dylan from the start.

Accounts of Dylan’s music normally begin with his immersion in the songs and style of Woody Guthrie, his first musical idol (and, he has said, his last), and with the folk revival that grew out of the left-wing hootenannies of the 1940s. This approach makes sense, but it has become overly familiar, and it slights the influence of the much larger cultural and political spirit, initially associated with the Communist Party and its so-called Popular Front efforts to broaden its political appeal in the mid-1930s, which pervaded American life during the 1940s—Bob Dylan’s formative boyhood years.

In order to take a fuller and fresher look at this important part of Dylan’s cultural background, I decided to focus on Popular Front music seemingly very different from Guthrie’s ballads and talking blues—the orchestral compositions of Aaron Copland. The choice may seem extremely odd. Yet even though the connections are now largely forgotten, Copland belonged to leftist musical circles in New York in the mid-1930s that also included some of the major figures in what was becoming the world of folk-music collecting. Copland’s beloved compositions of the late 1930s and the 1940s, including Billy the Kid and Rodeo, may sound today like pleasant, panoramic Americana, but they in fact contained some of the same leftist political impulses that drove the forerunners of the folk-music revival of the 1950s and ’60s. Dylan, meanwhile, grew up in a 1940s America where Copland was becoming the living embodiment of serious American music. Copland’s music and persona had no obvious or direct effect on the kinds of music Dylan performed and wrote as a young man, but the broader cultural mood that Copland represented certainly did. And insofar as Dylan’s career has in part involved translating the materials of American popular song into a new kind of high popular art—challenging yet accessible to ordinary listeners—his artistic aspirations and achievements are not dissimilar to Copland’s.

The second chapter concerns the Beat generation writers, in particular Allen Ginsberg. Not only did Dylan eagerly read the Beats before he arrived in Greenwich Village; he and Ginsberg befriended each other at what was, fortuitously, a critical moment in both of their careers. Once again, though, much as with the folk revival, understanding the Beats and their influence on Dylan requires moving back before the 1950s, to battles over literature and aesthetics fought out during World War II on and around the campus of Columbia University. The echoes of those battles—and the spirit of the so-called New Vision that the young Ginsberg and his odd friends promulgated—reappeared later in Dylan’s music, most emphatically in the songs on his two great albums completed in 1965, Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited. Dylan’s influence on Ginsberg, at several levels, in turn helped the poet write his great work of 1966, “Wichita Vortex Sutra.” And Ginsberg and Dylan’s personal and artistic connections, begun at the end of 1963, would last until Ginsberg’s death in 1997.

The remainder of Bob Dylan in America takes up Dylan’s career at selected and arbitrary but far from random moments: his concert at Philharmonic Hall at the end of October 1964, in which he tried out startling new songs such as “Gates of Eden” and “It’s Alright, Ma” (and which I happened to attend); the making of Dylan’s landmark album Blonde on Blonde in New York and Nashville in 1965–66; the Rolling Thunder Revue tour of 1975; and the birth of one of Dylan’s greatest songs, “Blind Willie McTell,” recorded (but not released) in 1983. The book then takes a long jump to 1992–93, when Dylan, his career out of joint for a decade, reached back for inspiration in traditional folk music and the early blues. The book covers this pivotal moment in Dylan’s career by examining two very different songs that Dylan recorded in 1993: “Delia,” one of the first blues songs ever written; and “Lone Pilgrim,” an old Sacred Harp hymn. The final chapters consider Dylan’s work from “Love and Theft” in 2001 through his album of Christmas music, Christmas in the Heart, released late in 2009. Although each chapter after Chapter Two takes a particular composition or event as its initial focus, none confines itself strictly to that subject. By roaming through other related material, sometimes leaping back and forth in time, I hope to discuss most of Dylan’s greatest work, including albums such as Blood on the Tracks, without losing sight of the other great work, in and out of the recording studio, on which I concentrate. I also hope to present some reevaluations of material I heard very differently when first released.

Approaching my subject this way means that people, places, and things sometimes appear and vanish, only to reappear later under somewhat different circumstances. The folklorist John Lomax, for example, turns up in the very first chapter as the head of the Archive of American Folk Song, in connection with the invention of a folksy, Popular Front aesthetic; then he turns up again, five chapters later, in connection with the blues singer Blind Willie McTell. Or to take a smaller but still important example: in Chapter One, the writers in and around the influential periodical Partisan Review turn up as anti-Stalinist leftist critics of Aaron Copland; in Chapter Two, the Partisan Review intellectual, critic, and Columbia English professor Lionel Trilling appears, at roughly the same time, the mid-1940s, as the ambivalent antagonist of Allen Ginsberg and the incipient Beat generation. Where absolutely necessary to keeping the story line clear, I have alluded to earlier appearances by various figures or groups. But to pause and point out all of these recurrences, and the cultural circuits they represent, would interrupt the flow of the narrative and turn the book into an overlong encyclopedia of music and literary history. Readers should thus be prepared to encounter characters or institutions already discussed earlier in the book, but in very different contexts—and, much as when these kinds of things happen in the rest of life, make the necessary adjustments of perception and understanding.

Although it traces the jagged arc of a mercurial artist, through thrilling highs and (more cursorily) crushing lows, Bob Dylan in America is chiefly concerned with placing Dylan’s work in its wider historical and artistic contexts. This has required recognizing Dylan as an artist who is deeply attuned to American history as well as American culture, and to the connections between the past and the present. Reflecting on “Love and Theft” before its release, I was impressed all over again by Dylan’s immersion in literature and popular music, especially American literature and music—something he would discuss at length a few years later in the first volume of Chronicles. But I was also impressed by his ability to crisscross through time and space. It could be 1927 or 1840 or biblical time in a Bob Dylan song, and it is always right now too. Dylan’s genius rests not simply on his knowledge of all of these eras and their sounds and images but also on his ability to write and sing in more than one era at once. Partly, this skill bespeaks the magpie quality that is the essence of Dylan’s modern minstrelsy—what many friends and critics early in his career called his sponge-like thirst for material that he might appropriate and make his own. Partly, it stems from some very specific innovations that Dylan undertook in the mid-1970s. But every artist is, to some extent, a thief; the trick is to get away with it by making of it something new. Dylan at his best has the singular ability not only to do this superbly but also to make the present and the past feel like each other.

Dylan has never limited himself to loving and stealing things from other Americans. But his historical as well as melodic themes have constantly recurred to the American past and the American present, and are built mainly out of American tropes and chords. There are many ways to understand him and his work; the efforts presented here describe him not simply as someone who comes out of the United States, or whose art does, but also as someone who has dug inside America as deeply as any artist ever has. He belongs to an American entertainment tradition that runs back at least as far as Daniel Decatur Emmett (the Ohio-born, antislavery minstrel who wrote “Dixie”) and that Dylan helped reinvent in the subterranean Gaslight Cafe in the 1960s. But he belongs to another tradition as well, that of Whitman, Melville, and Poe, which sees the everyday in American symbols and the symbolic in the everyday, and then tells stories about it. Some of those stories can be taken to be, literally, about America, but they are all constructed in America, out of all of its bafflements and mysticism, hopes and hurts.

One of the trickier difficulties in appreciating Dylan’s art involves distinguishing it, as far as is possible, from his carefully crafted, continually changing public image. To be sure, his image and his art are closely related, and each affects the other. The same could be said for any performing artist and for any number of literary figures, not just in our own time, but going back at least as far as that of Jenny Lind and Walt Whitman. But Dylan has been particularly skilled at manufacturing and handling his persona and then hiding behind it, and this can mislead any writer. In good times, as in recent years—when he has presented himself as the living embodiment of all the previous Bob Dylans wrapped into one, as well as of almost every variety of traditional and commercial American popular music—the image is powerful enough to transfix his admirers and deflect criticism of his music. (It can also invite contrarian debunking.) In bad times, as in much of the 1980s, Dylan’s unfocused image can prompt either unduly harsh criticism of everything he produces or loyalist efforts to praise it all, or at least some of it, beyond its worth.

Although I have backed away from focusing too much on Dylan’s image in American culture, an interesting topic in itself, I have tried to check my own evolving enthusiasms for and disappointments in Dylan as a public figure in considering his art—or at least, as in the chapter on the Philharmonic Hall concert in 1964, I have tried to acknowledge those feelings and incorporate them into my analysis. More an exercise in the historical appreciation of an artist’s work than a piece of conventional cultural criticism, the book dwells on some of the more interesting phases of Dylan’s career, and spends far less time on the less interesting ones. In order not simply to rehash familiar material, I have also devoted less space than I might have to the years from 1962 to 1966, which have attracted the most attention until now, while devoting more to Dylan’s work in recent years, on which historical writing has just begun to appear. Throughout, though, the book takes account of where and when I think Dylan has succeeded and where and when he has stumbled, even in his most fruitful periods.

Here, then, are a series of takes on Dylan in America. Read them as hints and provocations, written in the spirit that holds hints, diffused clues, and indirections as the most we can look forward to before returning to the work itself—to Dylan’s work and to each of our own.

The stairway down to the Gaslight Cafe, New York. (photo credit II)

* In a television interview with Ed Bradley, broadcast by CBS late in 2004, Dylan marveled at the lyrics of old songs such as “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” and mused: “I don’t do that anymore. I don’t know how I got to write those songs. Those early songs were almost magically written.”

PART I: BEFORE

1

MUSIC FOR THE COMMON MAN:

The Popular Front and Aaron Copland’s America

Early in October 2001, Bob Dylan began a two-month concert tour of the northern United States. In his first performances since the terrorist attacks of September 11, Dylan debuted many of the songs on his new album, “Love and Theft,” including the prescient song of disaster, “High Water (for Charley Patton).” Columbia Records, eerily, had released “Love and Theft” on the same day that the terrorists struck. How, if at all, would Dylan now respond to the nation’s trauma? Would he, for once, speak to the audience? What would he play?

The new tour had no opening act, but as a concert prelude the audience heard (as had become commonplace at Dylan’s shows) a prerecorded selection of orchestral music. And on this tour, Dylan began playing what may have seemed a curious choice: a recording of the “Hoe-Down” section of Aaron Copland’s Rodeo. Then Dylan and his band took the stage and, with acoustic instruments, further acknowledged the awfulness of the moment, while also marking Dylan’s changes and continuities over the years, by playing the country songwriter Fred Rose’s “Wait for the Light to Shine”:

When the road is rocky and you got a heavy load

Wait for the light to shine

For the rest of the month, through fifteen shows, Dylan opened with “Wait for the Light to Shine,” often after hitting the stage to “Hoe-Down.” He would continue to play snatches of Rodeo at his concerts for several tours to come, and now and then he would throw in the opening blasts of Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man or bits of Appalachian Spring. Copland’s music from the 1940s served as Dylan’s call to order, his American invocation. Sixty years on, whether he knew it or not, Dylan had closed a mysterious circle, one that arced back through the folk-music revival where he got his start to the left-wing New York musical milieu of the Great Depression and World War II.

Anyone familiar with Dylan’s music knows about its connections to the 1930s and 1940s through the influences of Woody Guthrie and, to a lesser extent, Pete Seeger. But there are other connections as well, to a broader world of experimentation with American music and radical politics during the Depression years and after. These larger connections are at times quite startling, especially during the mid-1930s, when shared leftist politics brought together in New York a wide range of composers and musicians not usually associated with one another. Thereafter, many of the connections are elliptical and very difficult to pin down. They sometimes involve not direct influence but shared affinities and artistic similarities recognized only in retrospect. Yet they all speak to Dylan’s career, and illuminate his artistic achievement, in ways that Guthrie’s and Seeger’s work alone do not. The most important of these connections leads back to Aaron Copland and his circle of politically radical composers in the mid-1930s.

On March 16, 1934, Copland participated in a concert of his own compositions, sponsored by the Composers’ Collective of the Communist Party–affiliated Workers Music League and held at the party’s Pierre Degeyter Club on Nineteenth Street in New York. Copland was still known, at age thirty-three, a decade after first making his mark, as a young, iconoclastic, modernist composer. The collective, with which Copland was closely associated, had been founded in 1932 to nurture the development of proletarian music, and it consisted of about thirty members. The Degeyter Club took its name from the composer of the melody of “The Internationale.”

The review of the concert in the Communist newspaper Daily Worker praised Copland for his “progress from [the] ivory tower” and hailed his difficult Piano Variations, written in 1930, as a major, “undeniably revolutionary” work, even though Copland “was not ‘conscious’ of this at the time.”1 A few months later, Copland, increasingly drawn to the leftist composers and musicians, won a songwriting contest, cosponsored by the collective and the pro-Communist periodical New Masses, for composing a quasi-modernist accompaniment to the militant poem “Into the Streets May First,” written by the poet Alfred Hayes, who is best-known today for his lyrics to the song “Joe Hill.” In the 1950s, Copland would publicly disown the piece as “the silliest thing I did.”2 At the time, though, he was proud enough of what he called “my communist song” to bring it to the attention of his friend the Mexican composer Carlos Chávez, and to note that it had been republished in the Soviet Union. The Daily Worker’s music reviewer later recalled that the contest judges agreed that Copland’s song was “a splendid thing.”3

Aaron Copland, circa 1930. (photo credit 1.1)

That reviewer, who was one of the founders of the Composers’ Collective and wrote under the pseudonym Carl Sands, was the Harvard-trained composer, professor, and eminent musicologist Charles Seeger. At this point, Seeger, a musical modernist, had little use for traditional folk music as a model for revolutionary culture. “Many folksongs are complacent, melancholy, defeatist,” he wrote, “intended to make the slaves endure their lot—pretty, but not the stuff for a militant proletariat to feed on.”4 A year later, though, the Communist Party, on instructions from the Comintern, abandoned its hyper-militant politics and avant-garde artistic leanings in favor of the broad political and cultural populism of the so-called Popular Front. The Composers’ Collective duly folded in 1936, but Seeger took the shift in stride. In 1935, he moved his family to Washington, D.C., to work as an adviser to the Music Unit of the Special Skills Division of the Resettlement Administration, the forerunner of the New Deal’s Farm Security Administration; and he and his second wife, the avant-garde composer Ruth Crawford Seeger, were able to collaborate with their friend John Lomax and his son Alan in helping to build the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress. In addition to collecting and transcribing traditional songs that were in danger of disappearing, the archive and its friends would encourage the development of folk music as a tool for radical politics—efforts that eventually helped inspire Bob Dylan and the folk revival of the 1950s and 1960s.

Members of the Seeger family, circa 1937. Left to right: Ruth Crawford Seeger, Mike Seeger, Charles Seeger, Peggy Seeger. Not shown are Charles’s children from his first marriage, including son Pete, then eighteen. (photo credit 1.2)

Charles’s son Peter, then a teenager, had accompanied his father and stepmother to hear Copland discourse at the Degeyter Club, and during the summer of 1935 he traveled with his father to a square dance and music festival in Asheville, North Carolina, run by the legendary folklorist and mountain musician Bascom Lamar Lunsford. The youngster was already a crack ukulele player, but in Asheville he heard traditional folk music for the first time, played by Lunsford on a cross between a mandolin and a five-string banjo—and it changed his life forever.

A few years later, after dropping out of Harvard and working under Alan Lomax at the Library of Congress, Pete Seeger teamed up with a revolving commune of folk artists, including a young songwriter discovered and recorded by Lomax, Woody Guthrie, to form the leftist Almanac Singers, who promoted union organizing, racial justice, and other causes with their topical songs. (The supervisor for one of the Almanacs’ recording sessions in 1942, Earl Robinson, had written the tunes for “Joe Hill” and the Popular Front classic “Ballad for Americans”—and in 1935 he had studied piano with Copland at the Workers Music League’s school.) In the late 1940s, the Almanac Singers evolved into the Weavers.

The Weavers’ recordings would later prove essential in introducing a younger generation, including Bob Dylan, to the music of Woody Guthrie and in sparking the broader folk-music revival. But the Weavers were not the only influential musical descendants of the Composers’ Collective—and not the only ones drawn to American folk music.

The Almanac Singers, 1942. Left to right: Agnes “Sis” Cunningham, Cisco Houston, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Bess Lomax Hawes. Hawes was John Lomax’s daughter. (photo credit 1.3)

Like the Seegers, Aaron Copland continued his musical career with his politics intact. After winning his Communist song award in 1934, Copland spent the summer with his teenage lover, the photographer and aspiring violinist Victor Kraft, at a cabin his cousin owned in Lavinia, Minnesota, alongside Lake Bemidji and just to the west of the Mesabi Iron Range. Copland worked hard on his abstract and purposefully radical formal work, Statements for Orchestra, but also relaxed and took in what he called the “amusing town” of Bemidji, nearby. As he told a radical friend in New York, the amusements included some political escapades:

It began when Victor spied a little wizened woman selling a Daily Worker on the street corners …5 From that, we learned to know the farmers who were Reds around these parts, attended an all-day election campaign meeting of the C.P. unit, partook of their picnic supper and [I] made my first political speech! … I was being drawn, you see, into the political struggle with the peasantry! I wish you could have seen them—the true Third Estate, the very material that makes revolution … When S. K. Davis, Communist candidate for Gov. in Minn. came to town and spoke in the public park, the farmers asked me to talk to the crowd. It’s one thing to think revolution, or talk about it to one’s friends, but to preach it from the streets—OUT LOUD—Well, I made my speech (Victor says it was a good one) and I’ll probably never be the same!

The “good one” for the Communist candidate in Bemidji was, as far as we know, the last political stump speech Copland ever delivered, and his slightly bemused, slightly awkward, and maybe self-ironic description—“the peasantry”? “the true Third Estate”? in northern Minnesota?—makes it sound out of character. But Copland and Kraft did seek out the “Reds around these parts” and joined in their political activity. “The summer of 1934,” Copland’s most thorough biographer writes, “found him no mere fellow traveler, but rather an active, vocal ‘red.’ ”6 Thereafter, and until 1949, Copland, if not a member of the Communist Party, was aligned with the party, its campaigns, and its satellite organizations, connections he would later try to minimize and evade under hateful and intense political pressure—and under oath.

Soon after he returned to New York, via Chicago, for the winter, Copland had his own reckoning with the Popular Front. But the first great musical sensation to come out of the Composers’ Collective group and Copland’s circle of friends after 1935 involved another young composer, Marc Blitzstein—who, many years later, would have a direct and profound impact on Bob Dylan, independent of the Popular Front folksingers. Born to an affluent Philadelphia family in 1905, Blitzstein had been a prodigy and made his professional debut at age twenty-one with the Philadelphia Orchestra, playing Liszt’s E-flat piano concerto. Like Copland, Blitzstein had studied piano and composition in Paris in the 1920s with the formidable Nadia Boulanger, but after the onset of the Depression, living in New York, he found himself attracted to the radical theater more than to the concert hall. He felt a special kinship with the founders of the left-wing, socially conscious Group Theatre, including Harold Clurman (who had shared an apartment with Copland in Paris), Clifford Odets, and Elia Kazan.

In 1932, Blitzstein wrote a one-act musical drama, The Condemned, based on the Sacco and Vanzetti case, a leftist cause célèbre, that was never produced. Through the mid-1930s, as a member of the Composers’ Collective, he wrote film scores and workers’ songs, including a submission to the songwriting contest that Copland won. All along, Blitzstein had begun turning to concepts of populist, modernist, left-wing musical theater, blending Marxist politics with jazz, Igor Stravinsky, cabaret, and folk songs. Bertolt Brecht and his musical collaborators Hanns Eisler and Kurt Weill had conceived and advanced these ideas in Germany before the Nazi takeover in 1933, and Eisler and Weill had brought them to New York as political émigrés. Earlier, Blitzstein had condemned Weill’s music as vulgar pandering, but now he had completely changed his mind. In the late summer of 1936, working at what he called a white heat, he completed a new proletarian musical play, The Cradle Will Rock.

A hard-bitten allegory of capitalist greed and corruption, capped by an uprising of organized steelworkers, The Cradle Will Rock was the first important American adaptation of the Brecht-Eisler-Weill style—and it caused a firestorm. As the show took shape, Blitzstein’s sponsor, the New Deal’s government-funded Federal Theatre Project, already suffering reprisals from conservatives in Congress, became panicky. Practically on the eve of the first scheduled preview performance, the project, citing impending budget cuts, shut down the production and ordered the theater padlocked. Thinking fast, Blitzstein’s collaborators—the young director Orson Welles and the producer John Houseman—vowed to defy the order, rented another theater, redirected ticket holders for the first preview to the new venue, and mounted an astounding sold-out debut. (The audience swelled into a standing-room-only crowd when the company invited passersby in for free.) The Actors’ Equity union had forbidden the cast to perform the piece, just as the musicians’ union had refused to allow its members to play in what had formally become a commercial production for less than union scale, and so, with Blitzstein himself playing the score from a piano onstage, the actors spoke and sang their parts from the house. The hastily planned, seemingly spur-of-the-moment debut was a political as well as an artistic sensation. After a brief run, Cradle reopened some months later, by popular demand, under the auspices of Welles and Houseman’s new Mercury Theatre company, and ran for an additional 108 performances.

Poster for the original production of The Cradle Will Rock, 1937. (photo credit 1.4)

Aaron Copland was among those present for the impromptu premiere, and it thrilled him. (“The opening night of The Cradle made history,” he wrote thirty years later, “none of us who were there will ever forget it.”)7 Defending the show against charges that it was nothing but leftist propaganda, Copland allowed that “a certain sectarianism” limited its appeal, but he praised its innovative combination of “social drama, musical revue, and opera,” and its clipped prosody and score.8* Copland, meanwhile, had moved away from the dissonant modernism of his earlier work, and he would soon venture beyond orchestral music to write film scores and ballets. But Copland’s own new direction had more in common with the all-American folk-song collecting of Charles Seeger and the Lomaxes that would later strongly affect Bob Dylan than it did with Blitzstein’s Brechtian musical theater (which would also affect Dylan’s work). Theirs were two very distinct artistic responses to the times, made by two ambitious, left-wing American Jewish composers and friends, one who was destined for international fame, the other for relative obscurity. Yet their sensibilities were closely related, at least in the mind of Aaron Copland.

Copland’s new, more open and melodious composing style, which he adopted around 1935 and called “imposed simplicity,” emerged in full in 1938, when he completed, for the impresario and writer Lincoln Kirstein, the music for a ballet, Billy the Kid, a stylized depiction of the outlaw’s life and death. At Kirstein’s suggestion, Copland consulted various cowboy song collections edited by John Lomax, looking for possible themes. Copland wound up choosing six cowboy songs and adapting them to his score. All of them appeared, at one point or another, in collections published by Lomax. Three—“Whoopie Ti Yi Yo,” “The Old Chisholm Trail,” and “Old Paint”—would in turn be recorded by Woody Guthrie in a famous series of sessions in 1944 and 1945 for the record producer Moe Asch, the founder of Folkways Records.

Copland’s simplified and more self-consciously popular music distressed some of his admirers, including the young composer David Diamond, who feared that Copland was selling out “to the mongrel commercialized interests.”9 And Copland himself, the vanguard innovator, seems to have been initially uneasy about quoting directly from American folk music, or at least the music of the Old West. He had, to be sure, borrowed from Mexican folk songs for El Salón México, a one-movement tone poem that he wrote between 1932 and 1936. That effort helped him shed the received artistic wisdom that folk music was intrinsically a static form that lacked vitality. He had also experimented with jazz elements in the 1920s, believing that they helped diminish what he called the “too European” sound of his music.10 And there certainly were precedents for incorporating American folk music into serious composition. The pioneering American modernist composer Charles Ives, whose work Copland had begun to champion in the early 1930s, had been including American folk songs, band music, and bugle calls in his songs, chamber pieces, and orchestral music for decades.

But Ives, who was something of a hermit, wrote music that was difficult for musicians to play and for audiences to understand, and he had been largely ignored. The Mexican tunes of El Salón had the advantage of at least sounding exotic. Jazz contained the rhythmic and modal magic of African-American music, which impressed even the Europeans. American cowboy music was different. Copland later said that he was “rather wary of tackling a cowboy subject,” since he had been born in Brooklyn, but there were artistic concerns as well.11 “I have never been particularly impressed with the musical beauties of the cowboy songs as such,” Copland wrote in a note published to accompany Billy the Kid’s premiere.12

Kirstein pushed Copland and persuaded him that having worked with Mexican folk songs, he should see what he could do with homegrown ones. Only after he sailed to Paris, however, where he composed the ballet while living on the Rue de Rennes, did Copland become “hopelessly involved” in rearranging Old West tunes.13 “Perhaps there is something different about the cowboy song in Paris,” he mused, not for a minute relinquishing his urbane cosmopolitanism. In his hands, what he called “the poverty stricken tunes Billy himself must have heard” became modern art.

Still, the songs were indubitably present in Billy the Kid; anybody could recognize them; indeed, Copland’s whole endeavor involved making sure that they were easily recognized. And if their presence helped make Copland’s music more popular and commercially viable, it also underscored Copland’s newfound attachment to his own variation of Popular Front aesthetics. By these lights, popular folk music, stories, and legends contained raw materials for new forms of art—and for a better world to come. The revolutionary artist’s task was to help entwine the party with the fabric of national life by seizing upon these popular cultural forms—from detective thrillers to high, lonesome ballads—and infusing them with revolutionary élan. Copland started out this program by mining and reinventing the cowboy tunes.

The compositional task he set himself was by no means simple, even though the results sounded that way. “It’s a rather delicate operation,” he wrote, “to put fresh and unconventional harmonies to well-known melodies without spoiling their naturalness.14 Moreover, for an orchestral score, one must expand, contract, rearrange and superimpose the bare tunes themselves, giving them if possible something of one’s own touch. That, at any rate, is what I tried to do.”

Copland succeeded, and in doing so created something special, a music unlike any that had ever been written, even by George Gershwin with his jazz-inflected rhapsodies and tone poems—an amalgamation of traditional American folk songs and avant-garde harmonics that retained, unspoiled, the songs’ “naturalness,” a synthesis that employed the unconventional modal and chromatic shifts characteristic of “difficult” music, yet that did not require a practiced ear to understand and enjoy.

After opening in Chicago in October 1938, Billy the Kid, and particularly its score, won both popular and critical acclaim. Over the next three years, Copland devoted himself chiefly to writing film scores, teaching, publishing two books, making a concert and lecture tour of Latin America, and serving as president of the American Composers Alliance, an enterprise he had helped to establish in 1937 to promote serious contemporary American music. As it happened, his pause from concert-hall composing coincided with a confusing period for the American Left. The signing of the Nazi-Soviet nonaggression pact in 1939 signaled a complete reversal of the Communist Party line, from endorsing antifascism to endorsing peace, and it formally brought an end to the Popular Front. But after Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941 (one month after Robert Zimmerman was born in Duluth), the party line changed again—and the renewal of antifascism caused a revival of the basic tenets of Popular Front politics and culture.

Copland, who unlike some artists in the Communists’ orbit remained loyal to the party during the Nazi-Soviet alliance, was happy to embrace and advance that revived sensibility—and so was the American public, as never before. After Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and the United States’ entry into World War II allied with the Soviets, the Popular Front style began spreading out far beyond the political and cultural margins. Enlisted against the Axis powers, what had once been a sectarian leftist impulse now looked and sounded patriotic, unifying, and mainstream. The war became popularized as the fight of the common man—the ordinary, dog-faced GI foot soldier—to vindicate democracy, alongside the common men of the other Allies. In politics, idealizations of the People, and of the international struggle against class and racial oppression, began turning up in the rhetoric of the warmer, deeply liberal elements of the New Deal. And in virtually every realm of American culture, high and low, Popular Front motifs and mannerisms helped to define the 1940s.

Copland did his part for the war effort by returning to his composing. In 1942 alone, he completed three of what would become his most beloved works—Lincoln Portrait, Fanfare for the Common Man, and, for the young choreographer Agnes de Mille, the ballet Rodeo. (Copland also received a commission initiated by his friend Martha Graham to write another ballet, which would appear in 1944 as Appalachian Spring.) All three pieces extended the “imposed simplicity” of Billy the Kid. Two of them celebrated the nation’s popular culture and democratic politics; the third was a lucid, modernist orchestral tribute, solemn but vibrant, to the unshackled egalitarian masses.

American folk music remained, for Copland, a major resource, in the Popular Front vein. Lincoln Portrait incorporated Stephen Foster’s “Camptown Races” and the old New England folk song “Springfield Mountain,” in a cowboy rendition that John Lomax had included (one critic called it a “stammering version”) in his first published song collection, and that Woody Guthrie later recorded for Moe Asch.15 These tunes helped Copland evoke what he perceived as Lincoln’s plebeian simplicity as well as the 1850s and 1860s, as part of a Popular Front paean to the Great Emancipator as a revolutionary democratic leader—a radical ideal that was also patriotic and blended easily enough with more anodyne celebrations of Honest Abe, typified by the sentimental early installments of Carl Sandburg’s widely read multivolume biography of Lincoln.

Rodeo included the cowboy song “Old Paint,” which Copland had used in Billy the Kid—but Copland also utilized American folk music that was country but not western. In 1937, Alan Lomax and his wife, Elizabeth, had trudged a Presto disc-recording machine across rutted roads in the hills of eastern Kentucky. In the town of Salyersville, they found the fiddler William Hamilton Stepp. The recording they made of Stepp performing a juiced-up version of the old fiddler’s march “Bonaparte’s Retreat” was so powerful that a transcription of it appeared in a song collection that John and Alan Lomax published in 1941, Our Singing Country. Copland may have heard the Lomaxes’ recording, but the scrupulous transcription (made by Pete Seeger’s stepmother, Ruth) would have been sufficient to provide him with what he turned into the opening melody of Rodeo’s “Hoe-Down” section, which would be loved by generations to come—including Bob Dylan.* Befitting the occasion of its composition, Fanfare for the Common Man sounds, in contrast to Rodeo, abstract and declamatory as well as majestic. Written on commission for the Cincinnati Symphony as a concert prelude to honor the Allies—one of seventeen commissioned by the orchestra’s conductor, Eugene Goossens—Fanfare can be understood as a coda to Lincoln Portrait, which Copland completed only a few months earlier. The title contains an obvious paradox. Fanfares, rooted in the music of the court, are supposed to herald the arrival of a great man, a noble. Copland’s Fanfare, however, heralded the noble groundlings, grunts, and ordinary men—not just their service and sacrifice in the war, but their very existence and their arrival in history. The title had more specific political connotations as well—for Copland borrowed it, as he later informed Goossens, from a widely publicized speech, “The Century of the Common Man,” delivered earlier in 1942 by the New Dealer most closely identified with pro-Soviet and Popular Front politics, Vice President Henry Wallace.

William Hamilton Stepp, circa 1937. (photo credit 1.5)

Copland reinvented the fanfare musically as well as thematically. Virtually all of the pieces that Goossens received—including one by an old comrade of Copland’s from the Composers’ Collective, Henry Cowell—conformed to the same basic model: brief and snappy; heavy on trumpets and on rolling, military snare drums; filled with triplets and other traditional flourishes; and either starting out at full blast or quickly building to it. Copland’s Fanfare, though, is stately and deliberate, perhaps the most austere fanfare ever written. Beginning with its opening crash and rumble, it builds slowly in sonority and complexity, moving by stages from dark, obscure tones to an almost metallic brilliance, soaring and then concluding with a bang, in a different key from where it began. In its dignified simplicity, it is also complex—a subtly esoteric piece of music written for the democratic masses as well as to honor them.

Copland’s works from 1942 vastly increased his popularity, and they remain, to this day, admired standards in the orchestral repertoire. Yet Copland’s broadening appeal also got him into trouble with some high-toned critics—a foreshadowing of greater trouble to come. The detractors included the composer and scholar Arthur Berger, who, though a leftist sympathizer and for a long time Copland’s friend, criticized Copland in the influential Partisan Review for his switch from writing what Berger called “severe” music to writing “simple” music.16 When Copland, unfazed, inserted Fanfare as the opening to the fourth movement of his Third Symphony in 1946, even his erstwhile kindred spirit the composer Virgil Thomson derided the symphony as evocative of “the speeches of Henry Wallace, striking in phraseology but all too reminiscent of Moscow.”17

These criticisms were of a piece with a more general repudiation of Popular Front culture—both in its explicitly left-wing political form and in the broader “little guy” impulses of the 1940s—that had been brewing for several years inside the anti-Stalinist Left. An up-and-coming critical avant-garde was refashioning the idea of modernism along the lines articulated by several of the critics in and around Partisan Review, above all Clement Greenberg—a view hostile to accessibility and that regarded any hint of the programmatic in the arts as redolent of realist philistinism, suspiciously Stalinist as well as aesthetically vapid. Fanfare, along with the rest of Copland’s work from the late 1930s on, fit in perfectly with what Greenberg had been denouncing since 1939 as “kitsch” and what Dwight Macdonald eventually defined as “mid-cult”—a style, Macdonald wrote, that “pretends to respect the standards of High Culture while in fact it waters them down and vulgarizes them.”18

The detractors had an important point when they attacked the purposeful subordination of art to politics. But they did not adequately appreciate Copland’s art when they failed to comprehend efforts to cut through the distinctions between sophistication and simplicity as anything other than pursuit of the party line. Simplifying music, Copland believed, need not mean cheapening it; it could, in fact, help form the basis of an American artistic style that would fuse “high,” “middle,” and “low,” elevating creatively interesting forms of popular culture while also popularizing more serious culture. That effort had aesthetic intentions and merits above and beyond politics. “The conventional concert public continued apathetic or indifferent to anything but the established classics,” he recalled, whereas “an entirely new public for music had grown up around the radio and phonograph.19 It made no sense to ignore them and to continue writing as if they did not exist. I felt that it was worth the effort to see if I couldn’t say what I had to say in the simplest possible terms.”

It is always important to remember that the idea of using popular culture as a takeoff point for a larger artistic quest was not limited to the music of the Popular Front; neither was it limited to the Left nor to musicians alone nor to the ferment of the 1930s and 1940s. Numerous giants in modern American culture, from across a wide political spectrum, tried to build something new and larger out of popular forms, among them Louis Armstrong, Willa Cather, John Ford, William Carlos Williams, Duke Ellington, Walker Evans, Edward Hopper, and Frank Lloyd Wright. Copland understood and felt a kinship with their efforts, with no narrow political agenda.

People’s Songs magazine June 1947. (photo credit 1.6)

Still, for Copland, the principles of “imposed simplicity” were inevitably bound up with his Popular Front political loyalties of the 1930s and 1940s, even as a diluted form of those loyalties entered the cultural mainstream. And although Copland was chiefly identified with the symphony concert hall, he did not completely lose touch with the more populist adaptations of American folk music being undertaken by his friend Charles Seeger’s boy Pete and by Pete’s leftist folksinger friends—adaptations that Copland found musically and politically sympathetic. At the very end of 1945, the younger Seeger, recently discharged from the army, was instrumental in founding a new organization, People’s Songs, which over the next five years promoted the use of radical-minded folk music in order to encourage left-wing union organizing and related causes. Joining Seeger on the group’s founding committee were members of the Almanac Singers and other notables on the New York leftist folk-music scene, including Woody Guthrie, Lee Hays, Agnes “Sis” Cunningham, Alan Lomax, and Josh White. A few years later, the Board of Sponsors of the expanded People’s Songs Inc. included Aaron Copland as well as Paul Robeson and Leonard Bernstein.

During the same summer of 1934 that Copland roused the “peasantry” of northern Minnesota, the newlyweds Abraham Zimmerman and Beatrice Stone Zimmerman, by complete coincidence, settled in Abraham’s hometown, Duluth—the port city of the Mesabi Iron Range, about 150 miles from Copland’s vacation cabin on Lake Bemidji. Zimmerman had a good job working as a senior manager for the Standard Oil Company, and he ran the company union. Seven years later, on May 24, 1941, Beatrice, known to all as Beatty, gave birth to the first of the couple’s two sons, Robert.

Bob Dylan’s proximity and debt to the World War II era and its aftermath always need emphasis. It is said that he owns the 1960s—but he is, of course, largely a product of the 1940s and 1950s. At the very end of the 1950s, he heard for the first time John and Alan Lomax’s greatest discovery in the field, the Louisiana ex-convict and folksinger Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter. Then he heard an album of Odetta’s, picked up on the folk revival, and traded in his electric guitar for a double-O Martin acoustic; a year later, he immersed himself in the romance of Woody Guthrie’s Bound for Glory and was well on the way to becoming Bob Dylan. Before that, when he was still Bob Zimmerman, a mixture of country and western, rhythm and blues, and early rock and roll dominated his listening and his first expeditions as a performer, while his reading, at Hibbing High School, embraced Shakespeare and the classics, Mark Twain, and Popular Front stalwarts like his particular favorite, the novelist John Steinbeck. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, he was immersed in the singers and musicians whom everyone heard: Frank Sinatra, the Andrews Sisters, Bing Crosby, Frankie Laine, and the original cast recording of Oklahoma! (choreographed by Copland’s sometime collaborator de Mille); Whoopee John Wilfahrt, Frankie Yankovic, and a host of other Midwest polka band leaders. And, at the movies, there were Woman of the North Country, On the Waterfront, The Law vs. Billy the Kid, and (above all for Zimmerman and his friends) Marlon Brando in The Wild One and James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause and Giant. Finally, although far less popular, on stacks of twelve-inch records (and then the flood of long-playing records released after 1948), as well as on the radio and on early television as well as in school, there was classical music, old and new—including the music of Aaron Copland.

Whoopee John Wilfahrt, bottom of stairway, and his band in a playful pose at the Wold-Chamberlain Minneapolis and St. Paul Airport, 1947. (photo credit 1.7)

Copland was virtually inescapable in the 1940s and 1950s, even for the less musically inclined. The leading music-appreciation textbooks of the day, by Martin Bernstein and Joseph Machlis, hailed him as “one of America’s greatest composers,” his music “straightforward without being banal, and thoroughly American in spirit,”20 including compositions in which local and regional music “is dissolved in personal lyricism, thereby assuming a value that extends beyond the particular time or place.”21 Copland wrote works intended especially for young performers and listeners; his Young Pioneers and Suite No. 1 for Young Pianists, performed by Marga Richter, appeared on an MGM Records album, Piano Music for Children by Modern American Composers in 1954. Early in its premier season in 1952, the pioneering “highbrow” television show Omnibus broadcast Rodeo, and a year later it aired Billy the Kid. A portion of Billy the Kid also served as the opening theme for the first and only “live” television Western series, Action in the Afternoon, starring Jack Valentine as a singing, guitar-playing cowboy, broadcast by CBS in 1953, two years before it began running a televised version of the radio series Gunsmoke, starring James Arness as Marshal Matt Dillon. (As Abe Zimmerman was in the appliance business, his family became the first in town to own a television, in 1952.) Copland also scored music for several movies, including those based on Steinbeck’s novels Of Mice and Men (1939) and The Red Pony (1949), and in 1950 his music for a William Wyler film, The Heiress, won the Academy Award for Best Original Musical Score.

Dylan has never disclosed when he first heard Copland’s music, and as it was so ubiquitous on the American scene, he may not even recall. Dylan did not take any music-appreciation course after the eighth grade, so he likely did not hear Copland at school. Still, in light of where and when he grew up, it would have been extraordinary if Dylan, as a boy or a teenager, had not heard, somewhere, something composed by Copland. And whether he first heard Copland’s music then or later, it has clearly impressed itself on him—as has, just maybe, Copland’s example. Although born forty years apart, both Copland and Dylan descended from Jewish immigrant forebears from Lithuania. Both were drawn to the legends of underdogs and outlaws like Billy the Kid, as well as to the youthful, leftist New York musical precincts of their respective times. Both soaked up the popular music of the American past (taking special interest in the balladry and mythos of the Southwest) and transformed it into their art, reconfiguring old songs and raising them to creative and iconic levels that the purist folklorists could never have reached.

Those are interpolations and interesting parallels. Without question, though, Copland contributed to the blend of music and downtown left-wing politics that in time produced the folk-music revival which in turn helped produce Bob Dylan. Long before Dylan had picked up Bound for Glory, Copland’s reinventions of folk songs and paeans to the common man had been part of the soundscape of 1940s and early 1950s America. The most familiar way of understanding Dylan’s musical origins goes back to Woody Guthrie. But another, strangely related way goes back to Aaron Copland, whose orchestral work raises some of the same conundrums that Dylan’s songs do—about art and politics, simplicity and difficulty, compromise and genius, love and theft.