[/caption]

[/caption]DESCRIPTION

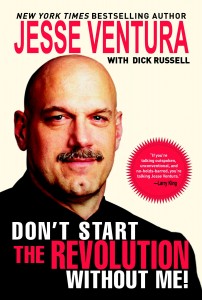

Jesse Ventura—former governor, wrestler, and Navy SEAL—on what's wrong with the Democrats, the Republicans, and politics in America.Jesse Ventura has had many lives—as a Navy SEAL, as a star of pro wrestling, as an actor, and as the governor of Minnesota. His previous books, I Ain't Got Time to Bleed and Do I Stand Alone?, were both national bestsellers. Don't Start the Revolution Without Me! is the story of his controversial gubernatorial years and his life since deciding not to seek a second term as governor in 2002. Written with award-winning author Dick Russell at a secluded location on Mexico's Baja Peninsula, Ventura's bestselling book reveals for the first time why he left politics—and why he is now considering reentering the arena with a possible independent run for the presidency.

In a fast-paced and often humorous narrative, Ventura pulls no punches in discussing our corrupt two-party system, the disastrous war in Iraq, and what he suspects really happened on September 11. He provides personal insights into the Clinton and Bush presidencies, and elaborates on the ways in which third parties are rendered impotent by the country's two dominant parties. He reveals the illegal role of the CIA in states like Minnesota, sensitive and up-to-date information on the Blackwater security firm, the story of the American spies who shadowed him on a trade mission to Cuba, and what Fidel Castro told him about who really assassinated President John F. Kennedy. This unique political memoir is a must-read for anyone concerned about the direction that America will take. 16 color photographs.

REVIEWS

Jesse Ventura—former governor, wrestler, and Navy SEAL—on what's wrong with the Democrats, the Republicans, and politics in America.Jesse Ventura has had many lives—as a Navy SEAL, as a star of pro wrestling, as an actor, and as the governor of Minnesota. His previous books, I Ain't Got Time to Bleed and Do I Stand Alone?, were both national bestsellers. Don't Start the Revolution Without Me! is the story of his controversial gubernatorial years and his life since deciding not to seek a second term as governor in 2002. Written with award-winning author Dick Russell at a secluded location on Mexico's Baja Peninsula, Ventura's bestselling book reveals for the first time why he left politics—and why he is now considering reentering the arena with a possible independent run for the presidency.

In a fast-paced and often humorous narrative, Ventura pulls no punches in discussing our corrupt two-party system, the disastrous war in Iraq, and what he suspects really happened on September 11. He provides personal insights into the Clinton and Bush presidencies, and elaborates on the ways in which third parties are rendered impotent by the country's two dominant parties. He reveals the illegal role of the CIA in states like Minnesota, sensitive and up-to-date information on the Blackwater security firm, the story of the American spies who shadowed him on a trade mission to Cuba, and what Fidel Castro told him about who really assassinated President John F. Kennedy. This unique political memoir is a must-read for anyone concerned about the direction that America will take. 16 color photographs.

PREVIEW

[lyrics]PROLOGUE

THE COUNTRY AT A CROSSROADS

“Gentlemen, I have had men watching you for a long time, and I am convinced that you have used the funds of the bank to speculate in the bread-stuffs of the country. When you won, you divided the profits amongst you, and when you lost, you charged it to the bank.... You are a den of vipers and thieves. I intend to rout you out.”

—President Andrew Jackson, to a delegation of bankers in 1832

There’s an old saying: the more things change, the more they stay the same. Since this book was published in the spring of 2008, a whole lot has happened that has Americans wondering whether we’re about to plunge into another Great Depression. At the least, we’re going through the worst economic crisis of my lifetime. And we’ve elected a new president who ran for office on a platform calling for change, whom millions of people are counting on to pull us out of this mess and all the other nightmares that the Bush administration has created.

Barack Obama is a great man who’s accomplished a remarkable thing, but he doesn’t have a magic wand. Our country lives a bit under this dream-like belief, and people need to understand that you don’t just come in and right all the wrongs. The federal government is a huge piece of machinery that’s always moving, and you just jump on. Your job is to attempt to guide and inch the machinery along, a little bit to this direction and a little bit to that. But it’s very difficult because of the bureaucracy and the enormousness of it. So the American people need to give Obama a chance, first of all—at least a year before they start passing judgment on him.

Now, I didn’t vote for him. I met Ralph Nader during the course of the election and thought he was kind of a cool guy. And I voted for Ralph. I call my vote a protest vote—none-of-the-above—because I do not vote for Democrats or Republicans. I believe the two-party system is corrupt, for reasons you’ll understand in reading this book, and I will always cast a protest vote until I see a quality in our elections with more choices than two.

Having said that, I’ll never forget my feelings on Election Day, when it became clear that Obama had won. I looked at my wife and it felt good. I mean, really good. I’d never believed in my lifetime that I would see a black man elected president. I felt very happy that I was alive to see this happen. Now maybe next it will be a woman. This makes sense when you look at it chronologically, because let’s not forget that in this country, blacks could vote before women could! After all these years of white males, hopefully a woman president will happen in my lifetime, too. (But not Sarah Palin. I think we need someone who knows that Africa is a continent and not a country).

I think Obama’s message was phenomenal. He ran a remarkable campaign and raised an unimaginable amount of money. However, I’m also extremely disappointed with who he’s chosen for his cabinet. He ran on a message of change, and yet the only person missing from the old Democratic guard is Robert Byrd! I mean, from Tom Daschle right on down the line to Hillary Clinton and the rest, it’s pretty much nothing but all the old Democrats from the ’90s. How is that change? To me it’s a step backward. I may be proven wrong, and I hope I am. I hope these people can be advocates for change, but they’re sure going to have to change their spots to do that.

So that part disappoints me. But I think Obama is being very smart, in that he appears to be governing from the center. You don’t graduate from Harvard Law School without being smart, and I think it’s about time we got somebody smart in there! George W. Bush is the worst president of my almost sixty years on this planet. He allowed the largest attack in the history of our country to occur on American soil but—he still has not caught Bin Laden, the supposed perpetrator. We haven’t even charged the guy! Bush has taken us into two wars and now Afghanistan is getting worse, so apparently we’re going to shift our troops from Iraq to Afghanistan to finish the job.

He leaves our economy in total shambles. I mean, he makes Richard Nixon look like the greatest of presidents. At least Nixon accomplished a few things. I cannot think of one thing that this guy has accomplished. Spending money contrary to all conservative beliefs . . . what has he done in eight years? I blame this country for electing him twice—if they truly did. And if they didn’t, then we’ve got a lot more problems than we thought we had.

I will state flat-out that George Bush, Dick Cheney, Condoleeza Rice, and other people from that administration should be charged with crimes. Vince Bugliosi, great prosecutor and lawyer that he is (remember, he got Charley Manson convicted), lays it all out in his new book, The Prosecution of George W. Bush for Murder. A prosecution is what ought to happen because Bush is responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people—our troops and Iraqis—with this trumped-up war. We were not in any imminent danger and the Bush administration knew it, yet did everything to make us think we were, all based upon lies. Why is it that they were allowed to get away with it? Where is the spine of our country today?

We’re going to need quite a backbone to weather the economic storm that’s upon us. Let me start on a personal note by recalling something the legislature did to me in 2002 toward the end of my term as governor of Minnesota, because it has repercussions today. What I had proposed in my last budget, when we were in a milder recession, was to lower the sales tax rate but expand it to include services. This is something I’ll go into detail about later in the book, but basically I was trying to bring us into a twenty-firstcentury economy. In Minnesota, we still had a sales tax that was implemented in a ’60s economy, when it was 70 percent goods and 30 percent services, so they taxed the goods. Well, it’s flip-flopped now to precisely the reverse, where everything is probably 80 percent services and 20 percent goods. The sales tax isn’t doing what it was cut out to do.

The legislature claimed I was raising taxes, figuring “taxes” as a “death word” that would defeat the maverick governor in the next election. So they refused to implement my budget, overriding both my vetoes. With smoke and mirrors, they used up all the state’s reserves—including all the funds they got from winning a multimillion-dollar lawsuit against the tobacco industry—doing everything they could not to pass the budget I’d proposed. Well, we’re talking Minnesota running close to a $5.8 billion deficit this year, which is probably one-sixth of the state budget. They have to somehow balance that. I’m not saying there wouldn’t be a recession in Minnesota today, because that’s everywhere—but now the state will get hammered worse than if they had passed my budget back in 2002.

On the federal level, really this whole housing mortgage crisis is a repeat of what happened to family farmers back in the ’80s. Farmers all over the Midwest were offered these fraudulent loans, told to grow-grow-grow, then the banks got them to buy-buy and mortgage-mortgage until the bottom fell out. And that brought in corporate farming. That’s the same thing they did—though I’m not sure exactly who they are—in the whole home mortgage industry.

I don’t want to hear a word from us criticizing Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez for nationalization anymore. Not that we go to the same extreme but, if what our government is doing isn’t nationalization to a certain degree, what would you call it? We’re investing $40 billion in AIG and giving them credit lines that could bring the federal funding up to $144 billion. That’s the biggest subsidy any American corporation has ever gotten. In exchange, the U.S. gets almost 80 percent of AIG’s stock.

I don’t like these huge bailouts, because there wasn’t enough stipulation put on them. These “wizards of finance” are the people who got us in trouble to begin with! The Associated Press did a 2008 analysis that showed the same banks getting taxpayer bailouts awarding nearly 600 big execs close to $1.6 billion in salaries, bonuses, and other benefits. At the same time, this Wall Street icon named Bernie Madoff perpetrates what looks like the biggest financial fraud in history, while the Securities and Exchange Commission that’s supposed to enforce the financial laws is looking the other way!

This is way beyond a sub-prime mortgage problem. Our national debt stands at $10.6 trillion dollars and keeps going up. Our children’s children will be paying for these bailouts with higher taxes while the Federal Reserve prints more money that devalues the purchasing power we’re hanging on to. We’re looking at, I would say, if not a depression then a borderline hard-core recession, with a lot of destitution coming in over the next few years before a rebound can take place.

Clearly, there has to be a revolution in our economic world. I’m talking about the disparity between the corporate white-collar types and the people doing the work. It’s been getting wider and wider, far more than in most foreign countries. Cut out the golden parachutes—especially in the auto industry. Here’s where I thought Mitt Romney, former governor of Massachusetts, came up with a phenomenal idea. He comes from the auto industry; his father saved it when he was governor of Michigan. Mitt said that letting GM, Ford, and Chrysler go bankrupt might be a good thing because it will then cause a total restructuring where you get the bozos out of there and put in new heads with a new train of thought. Like he said, eliminate the executive dining room and the corporate jets—all this stuff that creates hostility between the workers and management. All workers see are these guys flying around having fun, while they’re laboring every day trying to build a car.

You’ve got to destroy that system, bring in new management, and start building green cars. Sometimes adverse things happen but end up being for the better. We can take this whole mess, and if it’s done right—but I hold my breath—it could end up a hugely positive turnaround. That’s if we go in the direction we need to, like with solar energy and other alternative sources, and with all the jobs this direction will create. And we need to do them here—don’t ship out the manufacturing and don’t ship out the technology.

One other thing about our auto industry: I’ve learned that we’re at a disadvantage because built into every car manufactured is $1800 - $2000 worth of healthcare costs for the workers. This doesn’t happen with foreign autos because they have national healthcare. So they can add on that many more accessories and make their cars sell for the same price. Well, you’re gonna buy the one that’s the best deal and suits more of your needs, right? In order to make our autos competitive, you’d almost say we need to have national health insurance, too, wouldn’t you?

Speaking of insurance, I think that industry in general is the next one to start looking for bailouts like AIG got. They’re saying in Minnesota that by the end of ’09, one out of five cars on the road won’t be properly insured, contrary to state law. And if you get into an accident with one of those, then your insurance company has to foot the whole bill. It’s all out of whack.

Since we’re on the subject of fixing the economy, let me add: Will we now take our heads out of the sand and put through some social changes that would make a difference? Like how about finally legalizing marijuana and hemp, and turning them into renewable resources as they should be? And how about then taxing pot like the government does with liquor and cigarettes? Not only would this bring a new source of revenue, but we’d also stop spending millions to destroy it! Then the law enforcement people busting all the people for drugs could put their attention on things like going after the child molesters. Those predators are being released into neighborhoods, while drug offenders stay in jail?

It’s time we start changing our moral values in this country. We can’t afford anymore to put “crimes against yourself ”—consensual criminals—in prison. It’s time to end that. Let’s make marijuana a legal business, bring it aboveboard. Same with sports betting—another “illegal” business that’s not going away that the government could be making revenue on. In Minnesota alone, sports betting is a $3-billion-a-year industry that the state collects nothing from. Wouldn’t that help lower a $5-billion-plus deficit?

Okay, I’ve ranted on enough for a Prologue. I’m thinking it must be about time to head south for the winter.

CHAPTER 1

The Need for a New Adventure

“The first Westerners known to have landed on Baja were a ship’s crew dispatched by Hernan Cortés, looking for an ‘island of pearls’ that the Spanish conquistador had heard about from the Aztec ruler Moctezuma. During the 1500s a popular chivalric romance narrative also mentioned a race of Amazon women who ruled a gold-filled island. Their queen was called Califia, the place California. The early Spanish expeditioners apparently believed that the Baja terrain resembled that of the fictional island. Indeed, Baja was widely thought to be an island until the end of the seventeenth century. This was the first California. The peninsula would later be called Lower California, as differentiated from its neighboring American territory. (The Spanish adjective baja means ‘geographically lower.’)”

—Dick Russell, Eye of the Whale

When you’re at a crossroads, sometimes all you can do is take a reprieve from the fast lane. As I begin to write this book, I’m facing probably the most monumental decision of my fifty-six years on this planet. Will I run for president of the United States, as an independent, in 2008? Or will I stay as far away from the fray as possible, in a place with no electricity, on a remote beach in Mexico?

Right now I’m leaving Minnesota, where I was born and raised, been a pro wrestler and a radio talk-show host, and have served as both a mayor and a governor. I don’t know how much of an expatriate I’ll become. Looking at the political landscape of America today, my outrage knows few bounds.

We’re losing our constitutional rights because of the so-called “war on terror.” It reminds me of that line from the movie Full Metal Jacket: “Guess they’d rather be alive than free—poor dumb bastards!” Not me—once America is no longer what our country has stood for since 1776. We’ve gone backwards. When you look at how religious fanatics and corporate America are teaming up, we today are on the brink of fascism.

What infuriates me more than anything is that it’s my generation that is now in charge. We came out of the sixties, the Vietnam era. I served over there, but it’s now a historical fact that we were duped into that war by our leaders. Now, we’ve let it happen again with Iraq—a war based on lies and deceit that’s costing thousands of lives.

We’re also the generation that experimented more than any other with recreational drugs. If anybody should understand how wrongheaded the “war on drugs” is, it’s us. Marijuana should be legalized and regulated the same way as alcohol and tobacco. Bill Maher recently put it in this context: the Beatles took LSD and wrote Sgt. Pepper’s. Anna Nicole Smith’s autopsy turned up nine prescription drugs and she couldn’t dial 911. Yet the first drug is outlawed and you’ll go to jail for it, while all the others are given to you legally. I don’t get it.

And thirdly, we—“the free love generation”—are now telling our children to abstain from sex? When I spoke at Carleton College, I told the young people: “Unless they were a virgin on their wedding day, anyone who preaches abstinence to you is a hypocrite.” Two weeks later, Ann Coulter showed up at the same school, and one of the students raised his hand and asked her whether she’d been a virgin! It made the papers—and made me laugh. You know what Coulter did? Attacked the kid and changed the subject.

What also makes me so angry about America is that 50 percent or more of us don’t vote. Yet we’re out supposedly spreading democracy and spending billions of dollars to give it to Iraq—when half of us don’t even bother?

We’ve allowed our media to be turned into entertainment, rather than facts, enlightenment, and knowledge. We’ve gone from Woodward and Bernstein to Bill O’Reilly. From Walter Cronkite to Katie Couric. The death of Anna Nicole Smith received more coverage, for a longer period, than the assassination of President Kennedy did at the time.

Why is our government so secretive? If we are indeed a nation of the people, by the people, and for the people, how come they insist upon keeping us in the dark as much possible? I call it the dumbing-down of America, by both the media and the government. But the tragic fact is that we, the people, are becoming like lemmings racing in a suicidal pack toward the sea. And most of us won’t even face the fact that, because of our neglect, the seas are dying.

If you want good government, you must have an involved citizenry. Yet it seems like apathy is a contagious disease. People don’t pay attention to government because they don’t think it affects them. Well, you work five days a week. Why wouldn’t you pay attention to an entity that’s taking the fruits of your labor two of those days? Wouldn’t that be enough motivation to pay heed to what your tax dollars are being used for?

Today, the special interests have a stranglehold on our reality. Nobody is being told the truth. We’ve bought a bill of goods. I can’t believe everyone is so asleep. I achieved the impossible once—a wrestler becoming governor of one of our fifty states. Why is nobody else coming forward?

Or do I have to throw myself into the political ring again? And, if I do, is it worth the price that my family and I will have to pay?

This is the dilemma I’m facing. I can’t live with this apathy. I can’t tell myself it’s not happening. I have to stand up and talk about it. I love my country and what it was founded for. I believe deeply in its inherent freedoms. And we’re losing them. We’re losing more of them every day. I can’t just ignore it.... I don’t know about you. . . .

Psychologically, I needed to break away from the United States. I also felt it was time in my life to go on an adventure. I was still young enough, but I knew the window of opportunity was closing. From watching my parents pass on, I knew that your health becomes an issue at some point and eventually you’re not going to be able to travel. As you get older and older, you revert back to a childlike existence, where your little house and neighborhood are about the extent of your world. So, an adventure was important for me—not only physically, but mentally.

I needed to refocus, to do something that really went back to basics. And I found that, even in the twenty-first century, you can still be something of a Kit Carson. There are frontiers left to explore that are relatively untouched by humans. Some of these are located along the Mexican peninsula known as Baja California, almost a thousand miles of desert, mountains, and sea.

My wife Terry and I left Minnesota in the middle of winter, planning to drive our truck-camper, pulling a trailer with two wave runners, all the way across America and then over the border into Mexico. This was also an opportunity to renew our relationship. After playing the game of governor and First Lady for four years, in the public eye constantly, with our fully scheduled agendas, we’d often been like ships passing in the night.

Our two kids were grown up now, and had their own lives to lead. Tyrel was out in Hollywood, where he was working at becoming a screenwriter. Jade still lived in Minnesota, and was making plans to get married. So Terry and I were free in a way we’d really never been during all those years I’d spent in the limelight—as a pro wrestler, a movie actor, a radio personality, and finally as the improbable governor of the thirty-second state.

I’d have a lot of time along this journey to reflect.

At first, it feels strange leaving all the comforts of home behind. The three-story place we moved into after I decided not to seek a second term as governor is really my dream house. Built on a lake, the house is also right next to a railroad track. Even though I might be fishing and in complete solitude when a train goes by, it always awakensed me to the fact that the rest of the world is still moving. It’s a beautiful sight actually, when you’re out on the lake. Maybe that’s what helped put the wanderlust in me, too.

I live north of St. Paul, and it’s the first time I’ve ever lived east of the Mississippi River. As we pull out of our gate and head down along the shoreline of nearby White Bear Lake, I recall to Terry a story that my dad told me long ago. “This was a very famous lake back in the twenties and thirties. Back then, most of the laws were state-to-state, and if you hadn’t committed a crime in one particular state, the authorities there wouldn’t bother you. The folklore was, Al Capone and his gangsters had kind of a working agreement with Minnesota law enforcement—they wouldn’t do anything illegal if they could go on vacation to White Bear Lake. We were their home away from home.”

Terry laughed. “Your dad’s stories,” she said, “were amazing.”

TERRY: When we started doing the family holiday thing, it was unbelievable. His whole family had the best time sitting around arguing politics. I would just sit there, because my own family was really non-political. In southern Minnesota, when you went to someone’s home or a gathering, you didn’t talk about your religion, you didn’t ask how much anything cost that they owned, and you never mentioned politics! But his family would sound like they were beating the living heck out of each other mentally, and at the end they’d say, “Wow, what a great time we had!”

My dad George only got as far as the eighth grade, and worked as a laborer for the Minneapolis street department. He was ten years older than my mom, Bernice, who survived the Great Depression growing up on an Iowa farm and somehow put herself through nursing school. They both served in Africa during World War Two. He was an enlisted man, and she was a lieutenant. I remember when they’d get into an argument sometimes, he’d say, “Ah, the lieutenant’s on my case again. What the hell is them officers’ problem, anyway?”

I was born on July 15, 1951. My older brother Jan and I grew up in a two-story house in a lower-middle-class neighborhood of south Minneapolis. When I was in sixth grade, I used to set up a ring in our basement and stage different fights among my classmates. Sometimes I’d referee, sometimes I’d jump in there myself. Pro boxing was pretty big then in Minneapolis, and Jan and I loved listening to the bouts on the radio. I was probably no more than nine when my elementary teacher asked what I wanted to be when I grew up. When I said, “a pro boxer,” she told me that was a ridiculous idea.

Bernice was the disciplinarian in our family, and also handled all the finances, including our allowances. George was an easygoing type—except when it came to politics. We often watched the TV news while we ate dinner, and he argued back loudly whenever something pissed him off. He didn’t have much good to say about any politician, or our government. Minnesota’s own Senator Hubert Humphrey—whose son I eventually defeated in the governor’s race—he called “Old Rubber-Lip.” Richard Nixon was “The Tailless Rat.”

Years later, I remember we were watching TV together the night Nixon gave his famous “I am not a crook” speech during Watergate. “Look, you can see the son of a bitch is lying,” George said. I raised my eyebrows. “Come on, how do you know that?”

“Because anyone with sweat on their upper lip is lyin’ to you,” he said. I’ve thought of that a lot lately, watching George W. Bush and Dick Cheney.

Minnesota had quite a few people like my father, more than you find in most states. They liked straight shooters—politicians who weren’t afraid to put themselves on the line for what they believed. Even if those beliefs went against the grain of American public opinion. A statewide poll once showed that Minnesota voters favored “independents” above either the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party or the Republicans. The thing was, party didn’t matter so much. The man was what counted.

Think about some of the unique politicians that Minnesotans went for. Harold Stassen—called the “Boy Governor” when he was elected in 1939—came out fiercely against the isolationists, who were pretty powerful just before World War Two started. He actually stepped down as governor to join the Navy, ending up with the Pacific fleet fighting against the Japanese. Can you imagine any politician doing that today? For the most part, they wouldn’t let their third cousins serve! After the war, Stassen was instrumental in creating NATO and the United Nations. He then became best known as a “perennial candidate” for president. He ran ten times between 1948 and 1992, and the media made a laughingstock out of him. But I admired this man so much that, when he passed away during my term as governor, I ordered that he lie in state.

During the 1970s and ’80s, Rudy Perpich was elected governor twice. His detractors called him “Governor Goofy,” and he did do some curious things. He’d personally stop speeders on the freeways, and go back to the ghost town where he was born to “talk” to his ancestors. But Rudy was all right. I actually think he was ahead of his time. He proposed selling off the governor’s mansion to save money, and later I ended up shutting down the old mansion for a while after the legislature cut back on my budget. Rudy also worked hard to put Minnesota on the international map by traveling to many foreign countries, something I emulated with my trade missions to Mexico, Japan, China, and even Cuba.

Wendell Anderson was another remarkable governor, a former Olympic hockey player. After he found it necessary to raise people’s taxes fairly steeply, he traveled to every county telling the voters his reasons—and he won all eighty-seven counties in the next election.

In 1978, another Rudy—last name of Boschwitz, known for doing these hokey TV commercials for his Plywood Minnesota company—successfully ran for the U.S. Senate. He was replaced after two terms by a former wrestler who had no political experience, and who no one thought had a chance. That was Paul Wellstone, a liberal professor from Carleton College.

Between 1964 and 1984, from Hubert Humphrey to Walter Mondale, five out of the six presidential elections had a Minnesota native on one of the major party tickets. No other state in the union could claim that distinction.

Not that I paid too much attention to all this when I was growing up, except for my father’s political opinions. George had been a terrific swimmer—he could go across the Mississippi and back—and that gene apparently passed on to me. I was captain of the swim team at Roosevelt High, a district champion in the butterfly stroke. I also played defensive end on an unbeaten football team my senior year, got average grades, and ran with the same kids I had since grade school. We called ourselves the South Side Boys, and did a lot of camping, fishing, and drinking. I liked being a center of attention. And I liked being mischievous.

The one subject that grabbed me was “Mac” McInroy’s American history class. I’d get in some heated discussions there. And his admonition to his students stayed with me. He’d say, if we didn’t like the way things were, then stop bitching and start a petition and do something about it. America, he drilled into us, was a country where the individual could make a real difference.

My brother Jan had seen a Richard Widmark movie called The Frogmen and, after he graduated from high school in 1966, decided that’s what he wanted to be. Three years later, when I graduated, my parents badly wanted me to go on to college. I tried for a swimming scholarship to Northern Illinois, but I was only in the upper half of my class and not the upper third, so academically I didn’t qualify. I was working for the state highway department, repairing bridges, when I went along with a friend to hear what a Navy recruiter had to say. Even though Jan had come home on leave from Vietnam and tried to convince us this was a lousy idea, I ended up getting talked into enlisting. It was September 11, 1969.

My mom was especially upset about it. My dad opposed it, too. I think one of the driving forces, subconsciously, that led me to enlist was that every other member of my family was a war veteran. George had seven Bronze Stars for battles in World War Two. He fought in Normandy, Remagen Bridge, the Battle of the Bulge. He started off against Rommel in the North African desert, came up through Anzio in Italy, and finished in Berlin. Bernice was an Army nurse in North Africa. Jan was in Vietnam. Not that any of my family would have cared, but I must have wondered how I could sit down with them at the dinner table: three veterans and one nonveteran. Especially in a time of war.

So, I reported for boot camp with a buddy of mine named Steve. That was January 5, 1970. The date became relevant again for me in 1999: Steve would be there when I held a dinner party at the governor’s mansion for a bunch of old friends, the night after my inauguration. When he raised his glass for a toast, Steve said, “You guys probably don’t remember, but it was twenty-nine years to the day when Jesse and I went off to the Navy.”

The Navy SEALs were created by President John F. Kennedy. SEAL stands for Sea-Air-Land, an elite special team trained to carry out clandestine missions abroad. Basic training is called BUD/S (Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL). It lasted twenty-two weeks. It’s set up so that, literally, only the strong survive. There was an 80 percent dropout rate.

My first phase instructor was Terry “Mother” Moy (I’ll leave it to your imagination as to what the “mother” stood for). At my inauguration, he would stand behind me in full uniform, along with two others from my SEAL team. Later, “Mother” Moy told one of my biographers that, out of maybe 2,300 recruits who went through his training, he could only remember about a dozen. I was one of them. He recalled that I had a good sense of humor which, he said, “leaves you open to a little play, ’cause the instructors have a sense of humor, too.”

He was the scariest guy I ever met. My first day, we went through an obstacle course that took me forty-five minutes. Eventually, we’d have to do it in about ten. I came away with torn blisters hanging from my hands. When “Mother” Moy asked if any of us had any such “flappers,” I admitted that I did. He asked me to put out my right hand—and he ripped all the loose skin right off it. Then he had me do the same thing to my left hand, myself.

The first five weeks were all physical training—you ran everywhere you went—capped by what the instructors referred to as “Motivation Week” and we recruits called “Hell Week.” Those who made it through the pits of hell then went through nine weeks of demolition, reconnaissance, and land-warfare training, with new instructors to teach us how to blow things up. After that came six more weeks of underwater diving—how to swim with attack boards, navigate underwater with a compass at night, and dive scuba and deeper with mixed gas. Our mainstay was using re-breathers that emitted no bubbles.

Then it was on to jump school, becoming a skydiver. I was deathly afraid of heights. One of the reasons I joined the SEALs was to overcome that fear in my psyche. It worked—in the course of thirty-four parachute jumps, fast-roping out of a helicopter, or rappelling down a mountain.

After jump school, it was a week with the other services in SERE School (Survival, Escape, Resistance, and Evasion). We started out in the desert around Warner Springs, California, where even lizards can’t live, and ended up frying acorns for our meals. For the last twenty-four hours, you become a POW. They put me in a box so small that, given my size, they had to stand on it to close it. When they pulled me out—it may have been ten minutes, but it felt like ten hours—I couldn’t stand because my legs and arms were completely asleep. The infamous Chinese waterboarding procedure was also employed. This is where a towel is wrapped around your head and water is poured over your face, giving the sensation that you’re drowning. (It was recently deemed torture when the Americans applied it to the detainees in Iraq, but in SERE School they did it to our own soldiers!)

I moved on to SEAL Cadre, or SBI School, seven weeks of advanced guerrilla warfare in Niland, California. It was all in a jungle context, because we were being prepared for Vietnam. You learned it all, including how to conduct ambushes, kidnappings, and assassinations. And you fired every hand-held weapon known to man.

I was never the same after training, in a good way. Because then you truly know who you are, deep down inside. That would always be the scale, the measuring stick. No matter what I face in life, I always go back to my Underwater Demolition Team-SEAL training days and say to myself, “This is nothing, compared to that.”

The UDTs would rotate on tours overseas in six-month shifts. On my first deployment, I ended up headquartered at Subic Bay in the Philippines. It was like being on the frontier, and my friends and I were a wild bunch. Lot of cheap beer, lot of easy, pretty girls. I wore a necklace made out of shark’s teeth, sported an Australian bushman’s hat, and grew a beard and a Fu Manchu mustache. That’s when I started lifting weights, thinking maybe I’d play pro football after I got out.

From Subic Bay, our different detachments would be dispatched to Vietnam, Korea, Thailand, Hong Kong, and Guam. I spent time off the coast of Hanoi waiting with a Marine division for a Normandy-type invasion. That never happened. It was supposed to speed up “Peace with Honor,” Nixon’s political sell job. I served seventeen months of overseas deployment. Being a frogman, you defy death on a weekly basis, in war or peace.

In between my two deployments in Southeast Asia, we were conducting massive war games back in California. One pitch-black night, I was sure I was going to die. We were running “ops” on a river that was flowing like hell. I was in the first of two boats. We figured, hey, we’re going downstream and we don’t even have to paddle. This is gonna be a piece of cake. I was strapped in with ammo, lying there studying the shorelines, when all of a sudden we began hearing a dull roar. You can’t say anything, because on an op it’s all hand signals; you don’t want to give away the mission. Pretty soon the noise became deafening. My buddy, Rick, stood up in the front of the boat and said, “Oh my God, it’s a dam!”

Rick jumped out of the boat, made it to shore, and was able to run down and signal the second group so they wouldn’t go over. For us, it was too late. All six in my boat jumped into the river. Loaded down with ammo as I was, I landed in a churning mass of white water. I hit the side of the dam, desperately scratching for something to hang onto like the proverbial cat—but over the top I went.

When I landed, even though I was a championship swimmer, the current was so powerful that it spun me around like a pebble in a washing machine and kept sucking me under. I began accepting that I was not going to survive. Was I going to let my breath out and drown, or just hold it until I passed out? Those seemed like my only choices. I felt a sense of deep calm settle over me.

Then I had a crystal-clear vision of my parents. George and Bernice were bending over my casket, crying. I had the impression they were also angry—or maybe it was my own rage—that, after serving in Vietnam, now I was going to die in California! At the same time, I felt my boots scrape against the river bottom. And I shot up to the surface. After taking a few breaths, somehow I broke away from the washing-machine effect. Of the five guys who’d been with me, I was the one under the water longest, and the last one out.

For the first time, I began to think that there was a mysterious force guiding everyone’s life, a destiny, something bigger than coincidence. Because at least one of us should have drowned, but we all made it back alive.

When they sent divers over the next day to retrieve all the lost weapons, it was considered too dangerous even to try. Initially, the brass were going to court-martial me for losing my weapons . It was my first big confrontation with wrongheaded authority. I said, “Oh really? Well, I will then seek justice toward whoever did not brief us that there was a dam we’d have to somehow negotiate around. Because of their negligence, this almost cost the lives of five Navy SEALs.”

All of a sudden, the court-martial idea disappeared.

My last day of active duty, at the end of 1973, was close to the end of the American debacle in Vietnam. I was a naïve kid, and I didn’t know any better than many of my peers what was really behind it. Except for watching the news with my father, who’d said that stopping the “domino” effect of Communism was a shuck and that it wasn’t about anything other than money.

It was many years before certain painful truths about Vietnam became public. In 2004, when I was teaching at Harvard, Robert McNamara came to speak and show the documentary about himself, The Fog of War. That’s where the former secretary of defense first admitted that the Gulf of Tonkin incident never happened. Our government and our media told us that the North Vietnamese had fired at two of our ships, basically a declaration of war. That was the invented catalyst that escalated into a war that cost 58,000 American lives.

I was pretty worked up the night McNamara came to the Harvard campus. I don’t remember whether I threatened him or not, but certain faculty members told me they preferred that I not show up at his lecture. And I didn’t. Being one of the veterans sent into the Vietnam War under false pretenses, I wouldn’t have let him off the hook easily.

Leaving Minnesota . . . so many memories . . . I’d first moved back after my four years as a frogman ended had ridden rode for nine months with the South Bay Mongols motorcycle club. I was adrift then, with a whole host of choices before me, and really no clue about where I wanted to be or what I was going to do. Not so different, I suppose, than how I feel now, heading down a whole new road. But that was when Terry and I first met, in September of 1974.

I was working as a bouncer at the Rusty Nail, a bar in a Minneapolis suburb called Crystal. By day I was attending North Hennepin Junior College on the GI Bill. Even with a warning about how tough I’d find freshman English, I did discover a knack for it. In fact, I ended up with the highest grade in the class. I found I especially enjoyed the classroom discussions. And I ended up being recruited into a college play, The Birds. No, not the Hitchcock; the one by Aristophanes. It’s a comedy about these two people from Athens trying to escape from the city because of all the corrupt politicians. I was cast as Hercules.

Terry showed up at the door of the Rusty Nail on a Ladies’ Night. She was voluptuous, with long brown hair and the most amazingly beautiful eyes and smile. She’d already been carded by a cop at the door, and now she was headed my way, and I sure didn’t feel like any Hercules in my sport jacket and turtleneck sweater. I had to say something to her.

“Can I see your ID please?” I blurted out.

“But I just showed him,” she said, pointing at the cop.

“I don’t care how old you are, I just want to know your name,” I said, feeling kind of proud of such a good line. Well, she went through her purse until she found her ID again, presented it to me without a word, and kept right on going.

TERRY: This was the first time my two girlfriends and I had ever gone to a suburban bar. They were mostly full of softball players or used-car salesmen, we thought. But we did live in the suburbs, and we were all broke. I was a receptionist, holding down two jobs at the time, and they were going to school. So when we heard about this ladies’ night at the Rusty Nail, we decided to go.

When I first saw Jesse, he appeared to be the biggest thing in the entire place. Downstairs was where the rock and roll was, so that’s where we went first. But I couldn’t get that fellow at the door out of my head. Finally I said, “I’m going upstairs.” My girlfriend said, “You’re gonna go flirt with that guy and leave us down here; real nice.” But I couldn’t help myself.

Later that night, we ended up talking. She was from a rural area in southern Minnesota. I wasn’t calling myself Jesse Ventura yet, but I was already enamored of the world of wrestling. I’d gone to a pro bout at the Minnesota Armory featuring this huge, bleached-blond “bad guy” called “Superstar” Billy Graham. When I’d seen his total control of the crowd, I said to myself, “That’s what I want to do.” So I’d already gone into training just about every day at the Seventh Street Gym. I was big—six-foot-four and about 235 pounds—and I didn’t scare easy. Except, of course, around someone like Terry.

Lo and behold, the first thing she said to me was: “God! You look just like ‘Superstar’ Billy Graham!” (As soon as I got out of the Navy, I’d grown my hair down to my shoulders and bleached it blond).

“I ought to,” I said coolly. “He’s my older brother.”

Well, it turned out that she hated Graham. For being the villainous sort, always strutting around the ring and bragging to the crowd. Terry had started watching wrestling on TV with her dad, and still tuned in on Saturday nights before she went out. She gave me her work number and I called the next day to ask her on a date. I took her to a neighborhood bar called the Schooner. We hadn’t been there long when several cops came bursting through the door, yanked a fellow off a bar stool, and beat the crap out of him when he resisted. Nevertheless, Terry agreed to go out a second time. We went to the movies, my choice being Charles Bronson in Death Wish.

I guess she saw something beyond my macho exterior. A quality, she once told me, that she found soft, even sweet. Plus she had a terrific sense of humor. And I can be a pretty amusing fellow. Before long, I was taking Teresa Masters around to the gym to meet the guys.

TERRY: There was no doubt in my mind, after two weeks of knowing him, that I was absolutely, totally infatuated. I thought about him all the time; he was like nobody I had ever met before in my life. He had a vision and he had drive—such charisma. I got so scared, I tried to break up with him. I said, why don’t we also date other people. He said, nope, this is a one-way street, you’re either on it or you’re not.

We’d been dating for nine months when we got married, three days after my twenty-fourth birthday in July 1975. She was nineteen. And the best thing that ever happened to me.

November 3, 1998. Election night. Not all that long ago, but it seems like another lifetime. My family and I were driving down to Canterbury Park, a racetrack where we’d planned to hold our postelection party. I’d kept rising in the polls. That last weekend, the media had begun calling it a three-way horse race for the governorship. I knew I’d need some luck, that everything was going to have to fall into place. But I’d never doubted whether I could win. Otherwise, I would never have run in the first place.

The sun goes down early in November and the moon was very bright that night, with a fuzzy, broad ring around it like you see in Minnesota sometimes before it snows. There were several feathery ribbons of northern lights emanating from it, which drew our attention. I will never forget my son, Tyrel, suddenly saying from the back seat, very quietly: “Dad, something strange is going to happen tonight.”

“Do you think so, Ty?” I said.

“I’m telling you, it’s in the air. You can feel it.”

There had definitely been signs, especially over the last three days of nonstop campaigning into every region of the state. Fifteen hundred miles, thirty-four stops, in some rented RVs. We called it our No-Doz “72-Hour Drive to Victory Tour.” Kind of patterned after those whistle-stop train rides that candidates used to take.

Except we had an extra advantage called the Internet. My “Geek Squad” transmitted video clips and digital photos of all our rallies onto my Jesse Ventura website as soon as they happened, along with up-to-date information on where we were headed next. This was the first time any politician had really used the Internet; some of the pundits later compared it to JFK’s use of television during his presidential race in 1960.

TERRY: When his staff came up with the Winnebago tour idea for that final weekend, they said they really wanted me to participate. I’d stayed away from the campaign; the whole thing terrified me. I said, “I’m not going unless my parents come along.” My sister and my brother-in-law had just gotten a mobile home, and I rode with them. My brother-in-law drove, and most nights I stayed up, trying to keep him awake. In fact, I started singing cowboy songs to him. He finally told me if I sang any more he was going to crash the bus!

We’d kicked things off at sports bars in the northern suburbs of St. Paul, places like the BeBop and the Mermaid. I’d do twentyminute walk-throughs, and I was stunned at the size of the crowds. “There’s an old saying: if you don’t vote, don’t bitch!” I told them. And I had people coming up and telling me they hadn’t voted in twenty-five years, but they were turning out for me on Tuesday. I still see the face of this kid who approached me in the little town of Willmar. “Jesse,” he said, “you are us.” As the sun was setting one of those evenings, our caravan went past a sign painted in big orange letters on a bedsheet—“Ventura: Highway to the Future.”

It was heady stuff, but I sure wasn’t overconfident. I mean, it had been a fun ride, but I knew I could be back with my family soon on our thirty-two-acre horse ranch. And when this reporter asked, did I really think I could govern, I gave him a straight answer. I said, “I’ve jumped out of thirty-four airplanes in my life. I’ve dived 212 feet under the water. I’ve swum with sharks. I did things that would make Skip and Norm wet their pants.” (Referring to my two opponents, Democrat Skip Humphrey and Republican Norm Coleman). Which made all the media types laugh. Then I added, “This is simply governing and common sense and logic. Nothing more. Nothing less. I can do the job.”

TERRY: As we continued moving across the state, I knew. When you would pull into a tiny town at 11 o’clock at night, and find about Seven hundredu people freezing in a parking lot, holding up babies and old Jesse Ventura wrestling figures, I knew it was going to happen. But I still couldn’t fathom it. It was like saying we were going to get the Hope Diamond—but you have no clue what it looks like, feels like, or will be like when you own it.

We were an hour or two late getting to Hutchinson, Minnesota, our last stop of the night. We didn’t know what the turnout would be. It was a Sunday, and people had to go to work the next day. And there were all these people waiting! Hundreds of them! I’ll always remember Terry turning to me and saying, “My God, you’re going to win!”

We stole the headlines from the other two candidates at the most critical time of the election, the weekend before, when I think a lot of people make up their minds. A lot of the undecideds wait until virtually the eleventh hour. On that Tuesday, I heard rumors that people were flocking to the polls. Minnesota has a unique system where you don’t have to preregister to vote; you can do so right on election day. Supposedly, there were five times the number of people standing in the registration lines as in the voting lines. Over in Todd County, where they’d planned on as high as an 80 percent turnout, so many folks showed up that they ran out of printed ballots. When the polls closed that night, Minnesota ended up leading the country with a 61 percent voter turnout. Shamefully, the national average was 37 percent.

Of course, I didn’t know about these things until later. When I went to cast my ballot and the press asked me for interviews, I said it would have to be quick because my favorite TV show—The Young and the Restless—was about to come on. That afternoon, I lay down on my bed and put Oliver Stone’s brilliant movie JFK on the VCR.

Now, out at Canterbury Park, where the long shots sometimes come through, we started watching the returns. There was a feeling of electricity in the air. It looked more like a rock concert than anything, a partying crowd wearing blue jeans and ball caps and downing tap-beer. That was just the way I wanted it. When the first two exit polls were announced, I was, as everyone expected, in third place. Then, at 3 percent of the vote, I passed Coleman. And at 5 percent, I had a 120-vote edge over Humphrey. I figured, well, we could always say that, for one brief moment, we led. I went out and spoke to the crowd, and they whooped and hollered. Back in our private room, I noticed Terry’s face had gone pale.

TERRY: As the results from different areas of the state started coming in, I got more scared. I kept hearing, so-and-so wants to interview you. All these security people surround you and drag you through this crush of people, everybody’s hands out and touching you as you go. They were nice, but it was just so bizarre. No one cared before. No one was at the farm trying to grab onto me. I was out there going, “Please, someone, help me bail hay!”

It was five minutes to midnight. About 60 percent of the vote had been counted. I had 37 percent, Coleman stood at 34, and Humphrey was at 28. Out in the public area, kids were getting wild. They had several mosh pits going, passing bodies over their heads. I was asked to go out again and calm them down a bit. As I stood up, on the TV the local CBS affiliate put a check mark beside my name. Declaring me the winner!

I envisioned that famous headline from the 1948 presidential election: “Dewey Defeats Truman.” I quieted my people down, saying, “Wait a minute, how can they do that? Four out of ten Minnesotans haven’t even been counted yet. I’m not going out there and claiming victory, I’ll look like an idiot.”

Then the other two networks followed suit with check marks. Bill Hillsman, a true genius, who’d put together the TV and radio ads that many people felt pushed us over the top, walked over to me. He said, “Jesse, you trusted me with the ads, didn’t you?” I said yes. He said, quietly, “Then will you believe me on this?” “What?” I said. I felt numb, more than anything. “Trust me, Jesse. You’re the governor. They know. They haven’t been wrong since Dewey.”

TERRY: All of a sudden we looked and there was this check mark on the screen by his name. I was so terrified, I couldn’t think; I was hyperventilating. I went in the bathroom with two of my friends, because we were getting ready to go out onto a big stage. “What am I gonna do?” I asked them. “Oh, you’re the First Lady!” they shouted at me.

I went in the stall, sat down, and said, “Okay, nothing has changed. Even when you’re the First Lady, you still don’t get the stall with the toilet paper!” And my girlfriends just busted up.

I went out and told the crowd that nothing was official until I received those calls of concession from my two opponents. Forty-five minutes later, the phone rang twice. At the racetrack, the Rolling Stones were blaring. The people were splashing beer and highfiving and chanting like they do after a touchdown at pro football games: “Na-na-na-na, na-na-na-na, hey-hey-yeah, gooooood-bye!”

In a private room, Terry was curled up in her mother’s lap. She was crying. “I don’t know to handle this,” she said. “I wear leather and jeans. And I’m supposed to be Minnesota’s First Lady? I don’t think I can do it!”

I stood at a microphone and gazed out at the people. “Thank you for renewing my faith that the American Dream still lives,” I said.

“I didn’t make a lot of promises,” I told them. “I’m gonna do the best job I can do. I’m human. I’ll probably make mistakes. And let’s remember that we all make ’em. And if they’re mistakes from the heart, then you don’t have to apologize for them.”

I thanked my wife and kids, who, about a before year ago, had said to me, “Are you NUTS?!” With my voice trembling I thanked my parents, who were buried not far away in the Fort Snelling National Cemetery.

It was about three in the morning when the state troopers shuttled Terry and me over to a hotel about five hundred yards away. Somehow, Terry had the presence of mind to bring along some champagne. I popped the cork, we each took a swig and smiled at each other. “You’re the governor!” she said.

I could feel her excitement for me, but I also knew that she was terrified.

“And you’re the First Lady!” I said, and raised my glass to the woman who still means more to me than anything.

Headline: THE NATION: NOW, PRESIDENTIAL ‘BODY’ POLITICS; BUT SERIOUSLY, MR. VENTURA

Neither Vice President Al Gore nor Gov. George W. Bush of Texas is ripping his shirt off and wrapping a feather boa around his neck in the style of Gov. Jesse Ventura of Minnesota. But barely one year after Mr. Ventura’s unlikely election on the Reform Party ticket unnerved Democrats and Republicans, politicians have generally stopped joking about the professional wrestler turned politician.

Now they are scrutinizing Mr. Ventura’s every pronouncement, assembling focus groups and even making pilgrimages to St. Paul, Minnesota’s capital, searching for clues to a mystery that confounds even the most savvy politicians: How does a candidate excite the electorate and galvanize new voters when the public does not seem to be paying attention to politics?”

—The New York Times, September 19, 1999

Now, leaving Minnesota, all the tumult and the shouting seemed almost like another lifetime. The State Capitol dome faded into the skyline as dusk descended over our camper. We were heading south, way south, on a new adventure whose outcome was equally uncertain, equally unpredictable.

CHAPTER 2

The Road to the Arena

“There can hardly have been a weirder sight in this country’s political history: Minnesota governor-elect Jesse ‘The Body’ Ventura standing before a whooping crowd at his 1999 inaugural ball, sporting a garish, tasseled jacket, biker’s headscarf, shades, and a psychedelic Jimi Hendrix T-shirt, a pyrotechnical display fizzing behind him. That night, Ventura paraded and pumped his fists as if his prize were not the leadership of the nation’s 32nd state but a WWF smackdown victory, his head thrown back, his enormous mouth bisecting his enormous face, in the midst of a warrior’s cry that would make Howard Dean’s notorious howl look like a lullaby.”

—Boston Phoenix, March 2004

When I taught at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government in 2004, I called my last class “Wrestling, Then Politics: The Perfect Preparation for Serving.” People thought it was a joke but, when the class was over, they realized it hit the nail right on the head. First of all, in wrestling you have to be able to ad-lib and think on your feet. In politics, you’ll have questions fired at you and situations where you can’t run to your handlers. You need to be able to come up with an answer that doesn’t destroy you, and you’re going to learn the hard way that some of them will. Wrestling taught me that, because no matter how much you talk over what you’re going to do in a match, anything that can go wrong usually will.

The second thing I told the students was about how you had to sell yourself as a wrestler. I had to convince people to pay their hard-earned dollars to see me get my butt kicked, because I was billed as a villain. Well, in politics, you have to sell yourself similarly to convince people to vote for you, allow you to take their tax dollars, and run their government.

In both wrestling and politics, you travel a lot—especially to small towns. Wrestling is the only pro sport that goes to those places. We call them spot shows. It lets you get the message right out to the people. Because so much of it is visual today, wrestling makes you learn how to be very comfortable in front of a television camera. In that way, too, it’s a great stepping-stone to politics.

Finally, the wrestler is often not in public the same person he is in private, and I think it’s the same with the politician. Was I really Jesse “The Body” Ventura, a guy who struts around with bleached blond hair, six earrings, and feather boas around his neck? Of course not. That’s a total creation. So was the politically fabricated life of Mark Foley, the now-disgraced Republican Congressman from Florida who railed against gay marriage at the same time he was writing lurid e-mails to page boys.

Interstate 35, where I maneuvered our camper straight south out of Minneapolis on a gray, cold winter’s evening, was the identical road I’d driven thirty years earlier to begin my wrestling career. Back then, I’d been sending out pictures to different promoters around the country. One day I got a call from Bob Geigel in Kansas City, which was then one of the twenty-six wrestling territories in the U.S. He said my trainer had told him I had great potential and did I want to come for a tryout? Terry and I had started dating, and we were already pretty crazy about each other. But how could I pass up this opportunity? I hopped into my old Chevy, carrying a couple hundred bucks in my wallet, and took off.

“I missed you so bad,” I recall, glancing over at Terry as she jots a few notes into her travel journal. “I remember when you came to visit me once, after I’d been in Kansas City for a couple months, you cried when you saw how I was living.”

“Well,” Terry says, not looking up, “you were staying in basically a flophouse.”

“Twenty-three dollars a week,” I marvel, and shake my head. “But I’d seen worse in the service. Didn’t bother me.”

Pro wrestling had heroes and villains, and I’d already decided I was going to be a “bad guy” like “Superstar” Billy Graham. That’s why I grew the blond mane, to look like a California beach bum. I knew people in the Midwest would hate that. In a sport where Gorgeous George, Gorilla Monsoon, and The Crusher were some of the big names, I knew that plain old Jim Janos wasn’t going to cut the mustard. I’d always liked the name Jesse, maybe because of Jesse James. I looked on a map of California and my eyes landed on a highway that ran north of L.A. called Ventura. Jesse Ventura, the Surfer. Now that had a ring to it.

Besides Kansas City, on this trip we’d be passing right through Wichita, Kansas, where I made my debut against a “good guy” called Omar Atlas. Beforehand, Bob Geigel called us together and sketched out the plan. If the match was going well, I was to pick Omar up and throw him over the top rope. In those days, that was cause for automatic disqualification. So I went strutting out there, bragging and making fun of Omar, climbing up on the ropes and insulting the crowd when they booed me. And when I tossed Omar at them, and he landed with a thud and came up, I paraded around while the people got what they came for: They hated my guts. I spent two months around Kansas City earning peanuts for my matches, between thirty-five and sixty-five dollars per night.

“I knew then that I wanted to spend the rest of my life with you,” I said, turning again to Terry. “But I was still your typical noncommittal bachelor. Remember what you told me over the phone?”

“I said, I ain’t leavin’ up here unless I get a bigger commitment than ‘come on down and live with me.’”

“And I said, ‘Well, I guess I’ll just have to say ‘Will you marry me?’ You started crying, and said yes.”

By the time we got married that summer of 1975, I was moving on to Oregon, where the money was a little better. I traveled to towns all over the state for the next two years, at one point wrestling for sixty-three consecutive nights. I put 128,000 miles on the first car I ever owned, a ’75 Mercury Cougar, and often I was carpooling! For a while I billed myself as The Great Ventura and wore a mask—“to hide my good looks”—so tearing it off became a new gimmick. I fought a “battle royal” one time, where the promoters told everybody that the winner would get $50,000. I won all right, and probably got a little over a hundred bucks for my trouble. That’s the un-glorious part of the sport.

Other wrestlers went out carousing after their matches, while I went back to my hotel room alone and called Terry. This was tough on both of us, until she moved up.

TERRY: In Oregon, we lived in an apartment way off the beaten path, alongside an unpaved road that had a strip mall with wooden sidewalks. We only had one car, I didn’t know anybody, and I often just sat in an apartment with our dog for three or four days. I got in trouble with Jesse when I ran up a hundred dollar phone bill calling my mom, because I was so lonely.

In 1978, when an announcer started referring to me as Jesse “The Body” and the nickname stuck, I joined one of the bigger leagues, the American Wrestling Association, and went home to Minnesota. That’s where Adrian “Golden Boy” Adonis and I first became an unpopular tag team. There’s an old saying in the world of wrestling: “They gotta hate ya before they can love ya.”

I’ve often referred to pro wrestling as “ballet with violence.” Yes, it’s staged, as far as who’s going to be the winner, but it’s not fake. It’s really an art form, and one that requires careful discipline. When you smash your opponent with a folding chair, you’ve got to know how not to hurt him. When you get body-slammed, it’s painful, no way around it. But you get used to it.

At my induction into the WWE Hall of Fame a few years ago, I had a conversation with Ric Flair about backdrops. That’s a wrestling term that means getting thrown into the rope, flipping up in the air, and landing flat on your back. Ric would take at least three backdrops a night. He wrestles 300 nights a year, so that’s 900 backdrops. And he’s been wrestling thirty years—so that’s 27,000 backdrops. And that’s a minimal estimate! I find it amazing that Ric is still walking around, but he is.

In this particular dance, it’s the bad guy who leads—and who gets to be the most creative. I wore a flamboyant costume—starting with the wildly colored sunglasses and the big earrings, on to the bright colored tights, and the feather boas around my neck. I loved riling up the crowds. I’d pose in the ring and shout out things like, “Take a look at this body, all you women out there, and then take a look at that fat guy sitting next to you who’s eating pretzels and drinking beer. Who would you really rather be with? IT’S JESSE THE BODY EVERYWHERE!”

I developed a move called “The Body-breaker,” where I’d pick the other guy up across my shoulder and shake him relentlessly while I jumped up and down. “The most brutal man in wrestling!” I’d yell at the crowds. “The sickest man in wrestling! Mr. Money! Mr. Charisma! Mr. Show Business! Win if you can! Lose if you must! But always cheat!”

When the St. Paul Civic Center was sold out for one of my matches in 1980, I looked out upon thousands of fans, all yelling in a neardeafening chorus for a full five minutes: “Jes-SEE SUCKS! Jes-SEE SUCKS! Jes-SEE SUCKS!” I took it as a compliment, meaning I’d mastered my role as a ring villain. When I won the election in 1998, I recalled that night during my acceptance speech and told the celebrating crowd: “And you’re still cheering me!”

Well, in the eighties, the sport of wrestling became huge. I accepted an offer from Vince McMahon, Jr., to bid farewell to the old regional system and become part of a new World Wrestling Federation. Vince was a brilliant promoter, as well as being a smart and ruthless businessman. Before long, we were accepted by mainstream America. The first WrestleMania, in 1985, sold out Madison Square Garden. Terry and I arrived in a limousine. I was called “wrestling’s Goldilocks” by Sports Illustrated and featured alongside superstars from baseball and basketball. My tag-team events with Adrian were earning $3,000 a match. Adding it to the royalties from a Jesse Ventura action figure, I bought myself a Porsche Carrera.

One time, I was wrestling Hulk Hogan, and early in the match he kicked me in the jaw. I was supposed to go down first and then he’d wait. Except, as I started to fall, he kicked me a second time—and dislocated my jaw, only four minutes into a thirty-minute match. So we both had to ad-lib our way around this. Fortunately Hogan, being the professional that he was, allowed me to virtually beat him up for the next twenty minutes so he wouldn’t be touching my jaw. Afterward, I went immediately to the hospital so the doctors could yank it back into place.

Maybe it was a sign. I was due to wrestle Hogan for the world title in L.A.—the Sports Arena was already sold out—followed by bouts between us all over the country. I was destined to make millions, I was sure. Then, during a match in Phoenix, I couldn’t seem to catch my breath. I figured it was probably the hot autumn air of Arizona. But the next night in Oakland, it happened again. After flying on to San Diego the following morning, I went to bed instead of doing my customary workout. When I awoke at about one in the afternoon, I was drenched in sweat and my lungs were absolutely killing me. I thought it must be another bout of the pneumonia I’d suffered a few years earlier.

I checked myself into a hospital, where they did some preliminary tests. These showed blood clots in my lungs. If one of those broke loose and traveled to my heart or brain, I could have a heart attack or stroke. I was placed in intensive care, on intravenous heparin to try to dissolve the clots. The specialist called Terry and told her she’d better fly out, that I could die at any moment.

I spent six days in the hospital with Terry at my bedside. They put me on a blood thinner to prevent more clots from forming, but it also makes you a bleeder. I had to be on the medication for sixty days. There was no way I could go back in the ring during that period. My tour with Hogan was canceled.

I did return to wrestling, but only briefly. My last match was in Winnipeg, Canada, in the spring of 1986. My opponent was Tony Atlas, and I tossed him out of the ring. So I began and ended my career with an Atlas and a disqualification.

By then, Vince McMahon had called with another idea. “There’s never been a bad guy on the microphone,” he said. “Somebody who will do color commentating and side with the villains. Do you think you can do it?”

“Sure, I can,” I told him. And so, out of my latest round of adversity, began a new life as a broadcaster.

On the surface, farm country never seems to change. Driving down through southern Minnesota—where much of the farming takes place in our state—and then on past the endless cornfields of Iowa, it had all looked pretty much the same as a generation ago. Kansas, with its vast wheat fields, was as flat as ever.

But driving an interstate can be deceiving. Agribusiness keeps the big “factory farms,” livestock operations with thousands of cattle, hogs, and poultry, just far enough off the freeway so you can’t usually see or smell them. In the area closest to the feedlots, you can barely breathe even if you roll up your windows and shut off the outside air.

TERRY: When I was a kid, I thought the air in southern Minnesota was the most refreshing in the world. Today, the area where I grew up is so full of chemicals that I cannot go down there at certain times of the year (when they spray their fertilizers and weed killers) without getting terrible allergic reactions. When my daughter, Jade, and I were showing our horses, our eyes would water and our noses would run whenever we drove by the feedlots.

As First Lady I tried hard to work on the problems of feedlots because I also think they only produce toxic food. How can something good come from animals living in severe stress, fed nothing but chemicals and antibiotics and who knows what? None of that kind of meat can have the amount of protein, vitamins, and minerals that animals raised humanely on a normal diet could yield.

We’d bought a thirty-two-acre ranch in Maple Grove in the mid-1990s, because Terry wanted a place where she could have her horses on our own land, instead of boarding them. We hadn’t been living there long when I had to fight the county tax assessors to keep our farm status. They claimed I had another job. Well, many farm families have dual occupations. I remember my uncle farmed and my aunt worked for the county. Now they’re telling me that Terry could only be a housewife? It was she who baled the hay and fed the horses. I was going to sue them over that premise, until the county attorney told the assessor’s office to forget it.

The truth was, the government wanted to drive us out—because of pressure from developers. Eventually they succeeded.

TERRY: We sold the farm when it turned out I’d become allergic to everything in the barn, but mostly because of the development going on all around us. We were basically being surrounded, as the small family-owned farms sold off to contractors, because the owners were getting old or had died and the kids did not want the place. At Jade’s graduation party, right after Jesse left office, the farm land directly adjacent to us was being bulldozed, and the dust rolled over our property like a desert storm. We were told by our neighbors that the city council had said they would not look kindly at any farmland owners trying to hold onto their property as this area was being developed. We’d fought so hard to get the farm built and at that point just couldn’t see involving ourselves in another fight to hold onto it. Our home state has never been too kind to us in this regard.

It’s personal battles like this that got me involved in politics in the first place. I had no political intentions until I ran for mayor of Brooklyn Park, Minnesota, in 1990. I did it because I was outraged about developers coming into the area where we lived then, aiming to make housing subdivisions out of the few remaining potato fields. Rubber-stamped by the good old boys on the city council, they demanded that our neighborhood pay for curbs, gutters, and storm sewers through assessments—none of which we needed because we all already captured rain runoff in ditches. Where they planned to put the runoff water only added insult to injury: Since pollution laws forbade the developers from draining it into the Mississippi, they decided to pump the polluted storm water into a beautiful wetland about a block from my house. This would have completely destroyed the wetland.

It was supposed to be a nonpartisan election, meaning there are no parties, you run as who you are. But when it came down to the last week of the campaign, the heads of the state Democratic and Republican parties came together and wrote a joint letter to every citizen in Brooklyn Park, urging them to vote for the twenty-five-year incumbent. They called me “the most dangerous man in the city.” For a moment I took offense at that, but then I thought, well, as a professional wrestler and a Navy SEAL, they might be telling the truth here.

Anyway, I won, 65 percent to 35 percent, taking all twenty-four precincts of the city, including the one the incumbent lived in. A few weeks after the election, both parties independently came courting me to join them. I said, “But why would you want the most dangerous man in the city? Three weeks ago, you thought I was horrible. Now you’re welcoming me with open arms. You know what? I got elected pretty substantially on my own, so please explain why I would need you now.”

TERRY: I’d campaigned for him when he was running for mayor. Back then I thought politics was a really grand and noble thing to do. And I found out quickly, in the little town of Brooklyn Park, that it’s just dog-eat-dog, and stab everybody in the back. After he got elected, suddenly all these politicians were treating us like the best thing since sliced bread. It just seemed like everything was so underhanded and deceitful and dishonest. It was about who has power, who gets money, and what makes one side win.

Early in 1992, I began seeing these signs in people’s yards: “Independence Party—Dean Barkley for Congress.” I decided to check it out. Many of the people involved were centrists like me, disgruntled Democrats or Republicans who couldn’t stand what the two parties had turned into. The Independence Party of Minnesota wasn’t a wing like the Libertarians, who tend to want anarchy, or the Green Party, which was too far left to be my cup of tea. The Independence folks were all very passionate. It wasn’t about money, but about ideas. It wasn’t about power and control, but about the Constitution and “we the people,” and what government should be, in my opinion. And their charter stated unequivocally that, within the Independence Party, you only had to agree on 70 percent of the issues. That meant, if they could handle it, pro-choice and pro-life people could both be part of it; they could actually coexist with each other around other important issues.

So I affiliated with the Independence Party, which is where I met Dean Barkley and Doug Friedline and all of the people who eventually worked on my campaign for governor. Dean was a lawyer and small businessman who got inspired by Ross Perot’s third-party presidential campaign and decided to run for Congress. With a blend of fiscal conservatism and social liberalism, Dean gathered a healthy 16 percent of the vote in 1992.

Dean really is the hero of the third-party movement in Minnesota, more so than I am. He paved the way, and made my victory possible. In 1994, he ran for the U.S. Senate and got more than 5 percent of the vote, just the amount you need to achieve major party status under Minnesota law. That was my final year as mayor. I started working for talk radio, and had no inclinations for any further life in politics.

But in 1996, Dean decided to try for the Senate again and I agreed to become honorary chair of his campaign. His hometown of Annandale, Minnesota, is only eight miles away from my summer lake cabin. I was going to be up there over the Fourth of July anyway, and Dean asked me if I’d walk with him in the Annandale parade, because everyone knew me as the pro wrestler who’d served a term as mayor. As we started down Main Street in this little Midwestern town, all of a sudden the whole crowd started chanting: “Jesse! Jesse!”

Dean, smiling, leaned over to me and said, “See? The wrong candidate is running.” I smiled back at Dean and made what I thought was a joke. “Dean, I don’t want to go to Washington, but I’ll tell you what—I’ll run for governor of the state of Minnesota.”

Unfortunately or fortunately, whatever shoe you want to wear, Dean didn’t forget what I’d said off-the-cuff that day in the parade. He kept the pressure on me and, two years later, he’d be my campaign chair. My running was really thanks to Dean, who retained our major party status by getting 7 percent of the vote in 1996.