[/caption]

[/caption]DESCRIPTION

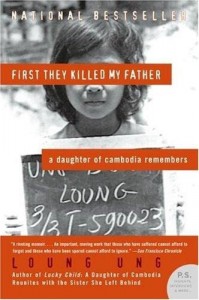

Written in the present tense, First They Killed My Father will put you right in the midst of the action--action you'll wish had never happened. It's a tough read, but definitely a worthwhile one, and the author's personality and strength shine through on every page. Covering the years from 1975 to 1979, the story moves from the deaths of multiple family members to the forced separation of the survivors, leading ultimately to the reuniting of much of the family, followed by marriages and immigrations. The brutality seems unending--beatings, starvation, attempted rape, mental cruelty--and yet the narrator (a young girl) never stops fighting for escape and survival. Sad and courageous, her life and the lives of her young siblings provide quite a powerful example of how war can so deeply affect children--especially a war in which they are trained to be an integral part of the armed forces. For anyone interested in Cambodia's recent history, this book shares a valuable personal view of events.REVIEWS

In 1975, Ung, now the national spokesperson for the Campaign for a Landmine-Free World, was the five-year-old child of a large, affluent family living in Phnom Penh, the cosmopolitan Cambodian capital. As extraordinarily well-educated Chinese-Cambodians, with the father a government agent, her family was in great danger when the Khmer Rouge took over the country and throughout Pol Pot's barbaric regime. Her parents' strength and her father's knowledge of Khmer Rouge ideology enabled the family to survive together for a while, posing as illiterate peasants, moving first between villages, and then from one work camp to another. The father was honest with the children, explaining dangers and how to avoid them, and this, along with clear sight, intelligence and the pragmatism of a young child, helped Ung to survive the war. Her restrained, unsentimental account of the four years she spent surviving the regime before escaping with a brother to Thailand and eventually the United States is astonishing--not just because of the tragedies, but also because of the immense love for her family that Ung holds onto, no matter how she is brutalized. She describes the physical devastation she is surrounded by but always returns to her memories and hopes for those she loves. Her joyful memories of life in Phnom Penh are close even as she is being trained as a child soldier, and as, one after another, both parents and two of her six siblings are murdered in the camps. Skillfully constructed, this account also stands as an eyewitness history of the period, because as a child Ung was so aware of her surroundings, and because as an adult writer she adds details to clarify the family's moves and separations. Twenty-five years after the rise of the Khmer Rouge, this powerful account is a triumph. 8 pages b&w photos.PREVIEW

[lyrics]author’s note

From 1975 to 1979—through execution, starvation, disease, and forced labor—the Khmer Rouge systematically killed an estimated two million Cambodians, almost a fourth of the country’s population.

This is a story of survival: my own and my family’s. Though these events constitute my experience, my story mirrors that of millions of Cambodians. If you had been living in Cambodia during this period, this would be your story too.

phnom penh

April 1975

Phnom Penh city wakes early to take advantage of the cool morning breeze before the sun breaks through the haze and invades the country with sweltering heat. Already at 6 A.M. people in Phnom Penh are rushing and bumping into each other on dusty, narrow side streets. Waiters and waitresses in black-and-white uniforms swing open shop doors as the aroma of noodle soup greets waiting customers. Street vendors push food carts piled with steamed dumplings, smoked beef teriyaki sticks, and roasted peanuts along the sidewalks and begin to set up for another day of business. Children in colorful T-shirts and shorts kick soccer balls on sidewalks with their bare feet, ignoring the grunts and screams of the food cart owners. The wide boulevards sing with the buzz of motorcycle engines, squeaky bicycles, and, for those wealthy enough to afford them, small cars. By midday, as temperatures climb to over a hundred degrees, the streets grow quiet again. People rush home to seek relief from the heat, have lunch, take cold showers, and nap before returning to work at 2 P.M.

My family lives on a third-floor apartment in the middle of Phnom Penh, so I am used to the traffic and the noise. We don’t have traffic lights on our streets; instead, policemen stand on raised metal boxes, in the middle of the intersections directing traffic. Yet the city always seems to be one big traffic jam. My favorite way to get around with Ma is the cyclo because the driver can maneuver it in the heaviest traffic. A cyclo resembles a big wheelchair attached to the front of a bicycle. You just take a seat and pay the driver to wheel you around wherever you want to go. Even though we own two cars and a truck, when Ma takes me to the market we often go in a cyclo because we get to our destination faster. Sitting on her lap I bounce and laugh as the driver pedals through the congested city streets.

This morning, I am stuck at a noodle shop a block from our apartment in this big chair. I’d much rather be playing hopscotch with my friends. Big chairs always make me want to jump on them. I hate the way my feet just hang in the air and dangle. Today, Ma has already warned me twice not to climb and stand on the chair. I settle for simply swinging my legs back and forth beneath the table.

Ma and Pa enjoy taking us to a noodle shop in the morning before Pa goes off to work. As usual, the place is filled with people having breakfast. The clang and clatter of spoons against the bottom of bowls, the slurping of hot tea and soup, the smell of garlic, cilantro, ginger, and beef broth in the air make my stomach rumble with hunger. Across from us, a man uses chopsticks to shovel noodles into his mouth. Next to him, a girl dips a piece of chicken into a small saucer of hoisin sauce while her mother cleans her teeth with a toothpick. Noodle soup is a traditional breakfast for Cambodians and Chinese. We usually have this, or for a special treat, French bread with iced coffee.

“Sit still,” Ma says as she reaches down to stop my leg midswing, but I end up kicking her hand. Ma gives me a stern look and a swift slap on my leg.

“Don’t you ever sit still? You are five years old. You are the most troublesome child. Why can’t you be like your sisters? How will you ever grow up to be a proper young lady?” Ma sighs. Of course I have heard all this before.

It must be hard for her to have a daughter who does not act like a girl, to be so beautiful and have a daughter like me. Among her women friends, Ma is admired for her height, slender build, and porcelain white skin. I often overhear them talking about her beautiful face when they think she cannot hear. Because I’m a child, they feel free to say whatever they want in front of me, believing I cannot understand. So while they’re ignoring me, they comment on her perfectly arched eyebrows; almond-shaped eyes; tall, straight Western nose; and oval face. At 5′6″, Ma is an amazon among Cambodian women. Ma says she’s so tall because she’s all Chinese. She says that some day my Chinese side will also make me tall. I hope so, because now when I stand I’m only as tall as Ma’s hips.

“Princess Monineath of Cambodia, now she is famous for being proper,” Ma continues. “It is said that she walks so quietly that no one ever hears her approaching. She smiles without ever showing her teeth. She talks to men without looking directly in their eyes. What a gracious lady she is.” Ma looks at me and shakes her head.

“Hmm …” is my reply, taking a loud swig of Coca-Cola from the small bottle.

Ma says I stomp around like a cow dying of thirst. She’s tried many times to teach me the proper way for a young lady to walk. First, you connect your heel to the ground, then roll the ball of your feet on the earth while your toes curl up painfully. Finally you end up with your toes gently pushing you off the ground. All this is supposed to be done gracefully, naturally, and quietly. It all sounds too complicated and painful to me. Besides, I am happy stomping around.

“The kind of trouble she gets into, while just the other day she—”Ma continues to Pa but is interrupted when our waitress arrives with our soup.

“Phnom Penh special noodles with chicken for you and a glass of hot water,” says the waitress as she puts the steaming bowl of translucent potato noodles swimming in clear broth before Ma. “Two spicy Shanghai noodles with beef tripe and tendons.” Before she leaves, the waitress also puts down a plate filled with fresh bean sprouts, lime slices, chopped scallions, whole red chili peppers, and mint leaves.

As I add scallions, bean sprouts, and mint leaves to my soup, Ma dips my spoon and chopsticks into the hot water, wiping them dry with her napkin before handing them back to me. “These restaurants are not too clean, but the hot water kills the germs.” She does the same to her and Pa’s tableware. While Ma tastes her clear broth chicken noodle soup, I drop two whole red chili peppers in my bowl as Pa looks on approvingly. I crush the peppers against the side of the bowl with my spoon and finally my soup is ready to taste the way I like it. Slowly, I slurp the broth and instantaneously my tongue burns and my nose drips.

A long time ago, Pa told me that people living in hot countries should eat spicy foods because it makes them drink more water. The more water we drink, the more we sweat, and sweating cleanses our bodies of impurities. I don’t understand this, but I like the smile he gives me; so I again reach my chopsticks toward the pepper dish, knocking over the salt shaker, which rolls like a fallen log onto the floor.

“Stop what you’re doing,” Ma hisses.

“It was an accident,” Pa tells her and smiles at me.

Ma frowns at Pa and says, “Don’t you encourage her. Have you forgotten the chicken fight episode? She said that was an accident also and now look at her face.”

I can’t believe Ma is still angry about that. It was such a long time ago, when we visited my uncle’s and aunt’s farm in the countryside and I played with their neighbor’s daughter. She and I had a chicken we would carry around to have fights with the other kids’ chickens. Ma wouldn’t have found out about it if it weren’t for the big scratch that still scars my face.

“The fact that she gets herself in and out of these situations gives me hope. I see them as clear signs of her cleverness.” Pa always defends me—to everybody. He often says that people just don’t understand how cleverness works in a child and that all these troublesome things I do are actually signs of strength and intelligence. Whether or not Pa is right, I believe him. I believe everything Pa tells me.

If Ma is known for her beauty, Pa is loved for his generous heart. At 5′5″, he weighs about 150 pounds and has a large, stocky shape that contrasts with Ma’s long, slender frame. Pa reminds me of a teddy bear, soft and big and easy to hug. Pa is part Cambodian and part Chinese and has black curly hair, a wide nose, full lips, and a round face. His eyes are warm and brown like the earth, shaped like a full moon. What I love most about Pa is the way he smiles not only with his mouth but also with his eyes.

I love the stories about how my parents met and married. While Pa was a monk, he happened to walk across a stream where Ma was gathering water with her jug. Pa took one look at Ma and was immediately smitten. Ma saw that he was kind, strong, and handsome, and she eventually fell in love with him. Pa quit the monastery so he could ask her to marry him, and she said yes. However, because Pa is dark-skinned and was very poor, Ma’s parents refused to let them marry. But they were in love and determined, so they ran away and eloped.

They were financially stable until Pa turned to gambling. At first, he was good at it and won many times. Then one day he went too far and bet everything on a game—his house and all his money. He lost that game and almost lost his family when Ma threatened to walk out on him if he did not stop gambling. After that, Pa never played card games again. Now we are all forbidden to play cards or even to bring a deck of cards home. If caught, even I will receive grave punishment from him. Other than his gambling, Pa is everything a good father could be: kind, gentle, and loving. He works hard, as a military police captain so I don’t get to see him as much as I want. Ma tells me that his never came from stepping on everyone along the way. Pa never forgot what it was like to be poor, and as a result, he takes time to help many others in need. People truly respect and like him.

“Loung is too smart and clever for people to understand,” Pa says and winks at me. I beam at him. While I don’t know about the cleverness part, I do know that I am curious about the world—from worms and bugs to chicken fights and the bras Ma hangs in her room.

“There you go again, encouraging her to behave this way.” Ma looks at me, but I ignore her and continue to slurp my soup. “The other day she walked up to a street vendor selling grilled frog legs and proceeded to ask him all these questions. ‘Mister, did you catch the frogs from the ponds in the country or do you raise them? What do you feed frogs? How do you skin a frog? Do you find worms in its stomach? What do you do with the bodies when you sell only the legs?’ Loung asked so many questions that the vendor had to move his cart away from her. It is just not proper for a girl to talk so much.”

Squirming around in a big chair, Ma tells me, is also not proper behavior.

“I’m full, can I go?” I ask, swinging my legs even harder.

“All right, you can go play.” Ma says with a sigh. I jump out of the chair and head off to my friend’s house down the street.

Though my stomach is full, I still crave salty snack food. With the money Pa gave me in my pocket, I approach a food cart selling roasted crickets. There are food carts on every corner, selling everything from ripe mangoes to sugarcane, from Western cakes to French crêpes. The street foods are readily available and always cheap. These stands are very popular in Cambodia. It is a common sight in Phnom Penh to see people on side streets sitting in rows on squat stools eating their food. Cambodians eat constantly, and everything is there to be savored if you have money in your pocket, as I do this morning.

Wrapped in a green lotus leaf, the brown, glazed crickets smell of smoked wood and honey. They taste like salty burnt nuts. Strolling slowly along the sidewalk, I watch men crowd around the stands with the pretty young girls at them. I realize that a woman’s physical beauty is important, that it never hurts business to have attractive girls selling your products. A beautiful young woman turns otherwise smart men into gawking boys. I’ve seen my own brothers buy snacks they’d never usually eat from a pretty girl while avoiding delicious food sold by homely girls.

At five I also know I am a pretty child, for I have heard adults say to Ma many times how ugly I am. “Isn’t she ugly?” her friends would say to her. What black, shiny hair, look at her brown, smooth skin! That heart-shaped face makes one want to reach out and pinch those dimpled apple cheeks. Look at those full lips and her smile! Ugly!

“Don’t tell me I am ugly! I would scream at them, and they would laugh.

That was before Ma explained to me that in Cambodia people don’t outright compliment a child. They don’t want to call attention to the child. It is believed that evil spirits easily get jealous when they hear a child being complimented, and they may come and take away the child to the other world.

the ung family

April 1975

We have a big family, nine in all: Pa, Ma, three boys, and four girls. Fortunately, we have a big apartment that houses everyone comfortably. Our apartment is built like a train, narrow in the front with rooms extending out to the back. We have many more rooms than the other houses I’ve visited. The most important room in our house is the living room, where we often watch television together. It is very spacious and has an unusually high ceiling to leave room for the loft that my three brothers share as their bedroom. A small hallway leading to the kitchen splits Ma and Pa’s bedroom from the room my three sisters and I share. The smell of fried garlic and cooked rice fills our kitchen when the family takes their usual places around a mahogany table where we each have our own high-backed teak chair. From the kitchen ceiling the electric fan spins continuously, carrying these familiar aromas all around our house—even into our bathroom. We are very modern—our bathroom is equipped with amenities such as a flushing toilet, an iron bathtub, and running water.

I know we are middle-class because of our apartment and the possessions we have. Many of my friends live in crowded homes with only two or three rooms for a family of ten. Most well-to-do families live in apartments or houses above the ground floor. In Phnom Penh, it seems that the more money you have, the more stairs you have to climb to your home. Ma says the ground level is undesirable because dirt gets into the house and nosy people are always peeking in, so of course only poor people live on the ground level. The truly impoverished live in makeshift tents in areas where I have never been allowed to wander.

Sometimes on the way to the market with Ma, I catch brief glimpses of these poor areas. I watch with fascination as children with oily black hair, wearing old, dirty clothes run up to our cyclo in their bare feet. Many look about the same size as me as they rush over with naked younger siblings bouncing on their backs. Even from afar, I see red dirt covers their faces, nestling in the creases of their necks and under their fingernails. Holding up small wooden carvings of the Buddha, oxen, wagons, and miniature bamboo flutes with one hand, they balance oversized woven straw baskets on their heads or straddled on their hips and plead with us to buy their wares. Some have nothing to sell and approach us murmuring with extended hands. Every time, before I can make out what they say, the cyclo’s rusty bell clangs noisily, forcing the children to scurry out of our way.

There are many markets in Phnom Penh, some big and others small, but their products are always similar. There is the Central Market, the Russian Market, the Olympic Market, and many others. Where people go to shop depends on which market is the closest to their house. Pa told me the Olympic Market was once a beautiful building. Now its lackluster façade is gray from mold and pollution, and its walls cracked from neglect. The ground that was once lush and green, filled with bushes and flowers, is now dead and buried under outdoor tents and food carts, where thousands of shoppers traverse everyday.

Under the bright green and blue plastic tents vendors sell everything from fabrics with stripes, paisley, and flowers to books in Chinese, Khmer, English, and French. Cracked green coconuts, tiny bananas, orange mangoes, and pink dragon fruit are on sale as are delicacies such as silver squid—their beady eyes watching their neighbors—and teams of brown tiger shrimp crawling in white plastic buckets. Indoors, where the temperature is usually ten degrees cooler, well-groomed girls in starched shirts and pleated skirts perch on tall stools behind glass stalls displaying gold and silver jewelry. Their ears, necks, fingers, and hands are heavy with yellow twenty-four-carat gold jewels as they beckon you over to their counters. A couple of feet across from the women, behind yellow, featherless chickens hanging from hooks, men in bloody aprons raise their cleavers and cut into slabs of beef with the precision of many years’ practice. Farther away from the meat vendors, fashionable youths with thin Elvis Presley sideburns in bell-bottom pants and corduroy jackets play loud Cambodian pop music from their eight-track tape players. The songs and the shouting vendors bounce off of each other, all vying for your attention.

Lately, Ma has stopped taking me to the market with her. But I still wake up early to watch as she sets her hair in hot rollers and applies her makeup. I plead with her to take me, as she slips into her blue silk shirt and maroon sarong. I beg her to buy me cookies while she puts on her gold necklace, ruby earrings, and bracelets. After dabbing perfume around her neck, Ma yells to our maid to look after me and leaves for the market.

Because we do not have a refrigerator, Ma shops every morning. Ma likes it this way because everything we eat each day is at its freshest. The pork, beef, and chicken she brings back is put in a trunk-sized cooler filled with blocks of ice bought from the ice shop down the street. When she returns hot and fatigued from a day of shopping, the first thing she does, following Chinese culture, is to take off her sandals and leave them at the door. She then stands in her bare feet on the ceramic tile floor and breathes a sigh of relief as the coolness of the tile flows through the soles of her feet.

At night, I like to sit out on our balcony with Pa and watch the world below us pass by. From our balcony, most of Phnom Penh looms only two or three stories high, with few buildings standing as tall as eight. The buildings are narrow, closely built, as the city’s perimeter is longer than it is wide, stretching two miles along the Tonle Sap River. The city owes its ultramodern look to the French colonial buildings that are juxtaposed with the dingy, soot-covered ground-level houses.

In the dark, the world is quiet and unhurried as streetlights flicker on and off. Restaurants close their doors and food carts disappear into side streets. Some cyclo drivers climb into their cyclo to sleep while others continue to peddle around, looking for fares. Sometimes when I feel brave, I walk over to the edge of the railing and look down at the lights below. When I’m very brave, I climb onto the railing, holding on to the banister very tightly. With my whole body supported by the railing I dare myself to look at my toes as they hang at the edge of the world. As I look down at the cars and bicycles below, a tingling sensation rushes to my toes, making them feel as if a thousand little pins are gently pricking them. Sometimes, I just hang there against the railing, letting go of the banister altogether, stretching my arms up high above my head. My arms loose and flapping in the wind, I pretend that I am a dragon flying high above the city. The balcony is a special place because it’s where Pa and I often have important conversations.

When I was small, much younger than I am now, Pa told me that in a certain Chinese dialect my name, Loung, translates into “dragon.” He said that dragons are the animals of the gods, if not gods themselves. Dragons are very powerful and wise and can often see into the future. He also explained that, like in the movies, occasionally one or two bad dragons can come to earth and wreak havoc on the people, though most act as our protectors.

“When Kim was born I was out walking,” Pa said a few nights ago. “All of a sudden, I looked up and saw these beautiful puffy white clouds moving toward me. It was as if they were following me. Then the clouds began to take the shape of a big, fierce-looking dragon. The dragon was twenty or thirty feet long, had four little legs, and wings that spread half its body length. Two curly horns grew out of its head and shot off in opposite directions. Its whiskers were five feet long and swayed gently back and forth as if doing a ribbon dance. Suddenly it swooped down next to me and stared at me with its eyes, which were as big as tires. ‘You will have a son, a strong and healthy son who will grow up to do many wonderful things.’ And that is how I heard of the news about Kim.” Pa told me the dragon visited him many times, and each time it gave him messages about our births. So here I am, my hair dancing about like whiskers behind me, and my hands flapping like wings, flying above the world until Pa summons me away.

Ma says I ask too many questions. When I ask what Pa does at work, she tells me he is a military policeman. He has four stripes on his uniform, which means he makes good money. Ma then said that someone once tried to kill him by putting a bomb in our trashcan when I was one or two years old. I have no memory of this and ask, “Why would someone want to kill him?” I asked her.

“When the planes started dropping bombs in the countryside, many people moved to Phnom Penh. Once here, they could not find work and they blamed the government. These people didn’t know Pa, but they thought all officers were corrupt and bad. So they targeted all the high-ranking officers.”

“What are bombs? Who’s dropping them?”

“You’ll have to ask Pa that,” she replied.

Later that evening, out on the balcony, I asked Pa about the bombs dropping in the countryside. He told me that Cambodia is fighting a civil war, and that most Cambodians do not live in cities but in rural villages, farming their small plot of land. And bombs are metal balls dropped from airplanes. When they explode, the bombs make craters in the earth the size of small ponds. The bombs kill farming families, destroy their land, and drive them out of their homes. Now homeless and hungry, these people come to the city seeking shelter and help. Finding neither, they are angry and take it out on all officers in the government. His words made my head spin and my heart beat rapidly.

“Why are they dropping the bombs?” I asked him.

“Cambodia is fighting a war that I do not understand and that is enough of your questions,” he said and became quiet.

The explosion from the bomb in our trashcan knocked down the walls of our kitchen, but luckily no one was hurt. The police never found out who put the bomb there. My heart is sick at the thought that someone actually tried to hurt Pa. If only these new people in the city could understand that Pa is a very nice man, someone who’s always willing to help others, they would not want to hurt him.

Pa was born in 1931 in Tro Nuon, a small, rural village in the Kampong Cham province. By village standards, his family was well-to-do and Pa was given everything he needed. When he was twelve years old, his father died and his mother remarried. Pa’s stepfather was often drunk and would physically abuse him. At eighteen, Pa left home and went to live in a Buddhist temple to get away from his violent home, further his study, and eventually became a monk. He told me that during his life as a monk, wherever he walked he had to carry a broom and dustpan to sweep the path in front of him so as not to kill any living things by stepping on them. After leaving the monastic order to marry Ma, Pa joined the police force. He was so good he was promoted to the Cambodian Royal Secret Service under Prince Norodom Sihanouk. As an agent, Pa worked undercover and posed as a civilian to gather information for the government. He was very secretive about his work. Thinking he could fare better in the private sector, he eventually quit the force to go into business with friends. After Prince Sihanouk’s government fell in 1970, he was conscripted into the new government of Lon Nol. Though promoted to a major by the Lon Nol government, Pa said he did not want to join but had to, or he would risk being persecuted, branded a traitor, and perhaps even killed.

“Why? Is it like this in other places?” I asked him.

“No,” he says, stroking my hair. “You ask a lot of questions.” Then the corner of his mouth turns upside down and his eyes leave my face. When he speaks again, his voice is weary and distant.

“In many countries, it’s not that way,” he says. “In a country called America it is not that way.”

“Where is America?”

“It’s a place far, far away from here, across many oceans.”

“And in America, Pa, you would not be forced to join the army?”

“No, there two political parties run the country. One side is called the Democrats and the other the Republicans. During their fights, whichever side wins, the other side has to look for different jobs. For example, if the Democrats win, the Republicans lose their jobs and often have to go elsewhere to find new jobs. It is not this way in Cambodia now. If the Republicans lost their fights in Cambodia, they would all have to become Democrats or risk punishment.”

Our conversation is interrupted when my oldest brother joins us on the balcony. Meng is eighteen and adores us younger children. Like Pa, he is very soft-spoken, gentle, and giving. Meng is a responsible, reliable type who was the valedictorian of his class. Pa just bought him a car, and it seems he uses it to drive his books around instead of girls. But Meng does have a girlfriend, and they are to be married when he returns from France with his degree. He was to leave for France on April 14 to go college, but because the thirteenth was New Year’s, Pa let him stay for the celebration.

While Meng is the brother we look up to, Khouy is the brother we fear. Khouy is sixteen and more interested in girls and karate than books. His motorcycle is more than a transportation vehicle; it is a girl magnet. He fancies himself extremely cool and suave, but I know that he is mean. In Cambodia, if the father is busy with work and the mother is busy with babies and shopping, the responsibility of disciplining and punishing the younger siblings often falls on the oldest child. In our family, because none of us fear Meng, this role falls to Khouy, who is not easily dissuaded by our charms or excuses. Even though he’s never carried out his threat to hit us, we all fear him and always do what he says.

My oldest sister, Keav, is already beautiful at fourteen. Ma says she will have many men seeking her hand in marriage and can pick anyone she wants. However, Ma also says that Keav has the misfortune to like to gossip and argue too much. This trait is not considered ladylike. As Ma sets to work shaping Keav into a great lady, Pa has more serious worries. He wants to keep her safe. He knows that people are so discontent they are taking their anger out on the government officers’ families. Many of his colleagues’ daughters have been harassed on the streets or even kidnapped. Pa is so afraid something will happen to her that he has two military policemen follow her everywhere she goes.

Kim, whose name in Chinese means “gold,” is my ten-year-old brother. Ma nicknamed him the little monkey” because he is small, agile, and quick on his feet. He watches a lot of Chinese martial arts movies and annoys us with his imitations of the movies’ monkey style. I used to think he was weird, but having met other girls with brothers his age, I realize that older brothers are all the same. Their whole purpose for being is to pick on you and provoke you.

Chou, my older sister by three years, is the complete opposite of me. Her name means “gem” in Chinese. At eight, she is quiet, shy, and obedient. Ma is always comparing us and asking why I cannot behave nicely like her. Unlike the rest of us, Chou takes after Pa and has unusually dark skin. My older brothers kid her about how she really isn’t one of us. They tease her about how Pa found her abandoned near our trashcan and adopted her out of pity.

I am next in line and at five, I am already as big as Chou. Most of my siblings regard me as being spoiled and a troublemaker, but Pa says I am really a diamond in the rough. Being a Buddhist, Pa believes in visions, energy fields, seeing people’s aura, and things other people might view as superstitious. An aura is a color that your body exudes and tells the observer what kind of person you are; blue means happy, pink is loving, and black is mean. He says though most cannot see it, all people walk around in a bubble that emits a very clear color. Pa tells me that when I was born he saw a bright red aura surrounding me, which means I will be a passionate person. To that, Ma told him all babies are born red.

Geak is my younger sister who is three years old. In Chinese Geak means “jade,” the most precious and loved of all gems to Asians. She is beautiful and everything she does is adorable, including the way she drools. The elders are always pinching her chubby cheeks, making them pink, which they say is a sign of great health. I think it is a sign of great pain. Despite this, she is a happy baby. I was the cranky one.

As Meng and Pa talk, I lean against the railing and look at the movie theater across the street from our apartment building. I go to a lot of movies and because of who Pa is, the theater owner lets us kids in for free. When Pa goes with us, he always insists we pay for our tickets. From our balcony I can see a big billboard over the theater portraying this week’s movie. The billboard shows a large picture of a pretty young woman with wild, messy hair and tears streaming down her cheeks. Her hair, at a closer inspection, is actually many little writhing snakes. The background depicts villagers throwing stones at her as she runs away while trying to cover her head with a traditional Khmer scarf called a “kroma.”

The street below me is quiet now, except for the sound of straw brooms sweeping the day’s litter into small piles on side streets. Moments later, an old man and a young boy come by with a large wooden cart. While the man accepts a few sheets of riel from the storefront owner, the boy shovels the garbage onto the cart. After they are done, the old man and the boy pull the cart to the next pile of garbage.

Inside our apartment, Kim, Chou, Geak, and Ma sit watching television in the living room while Khouy and Keav do their homework. Being a middle-class family means that we have a lot more money and possessions than many others do. When my friends come over to play, they all like our cuckoo clock. And while many people on our street do not have a telephone, and though I am not allowed to use one, we have two.

In our living room, we have a very tall glass cabinet where Ma keeps a lot of plates and little ornaments, but especially all the delicious, pretty candies. When Ma is in the room, I often stand in front of the cabinet, my palms pressing flat against the glass, drooling at the candies. I look at her with pleading eyes, hoping she will feel bad and give me some. Sometimes this works, but other times she chases me away with a swat to the bottom, complains about my dirty handprints on her glass, and says that I can’t have the candies because they are for guests.

Aside from our money and possessions, middle-class families, from what I can see, have a lot more leisure time. While Pa goes off to work and we children to school every morning, Ma does not have too much to do. We have a maid who comes to our house every day to do the laundry, cooking, and cleaning. Unlike other children I don’t have to do any chores because our maid does them for us. However, I do work hard because Pa makes us go to school all the time. Each morning as Chou, Kim, and I walk to school together, we see many children not much older than I am in the streets selling their mangoes, plastic flowers made from colorful straws, and naked pink plastic Barbie dolls. Loyal to my fellow kids, I always buy from the children and not the adults.

I begin my school day in a French class; in the afternoon, it’s Chinese; and in the evening, I am busy with my Khmer class. I do this six days a week, and on Sunday, I have to do my homework. Pa tells us every day that our number one priority is to go to school and learn to speak many languages. He speaks fluent French and says that’s how he’s able to succeed in his career. I love listening to Pa speak French to his colleagues and that’s why I like learning the language, even if the teacher is mean and I don’t like her. Every morning, she makes us stand single file facing her. Holding our hands straight out, she inspects our nails to see if they are clean, and if not, hits our hands with her pointing stick. Sometimes she won’t let me go to the bathroom until I ask permission in French. “Madam, puis j’aller au toilet?” The other day she threw a piece of chalk at me because I was falling asleep. The chalk hit me on my nose and everyone laughed at me. I just wish she would teach us the language and not be so mean.

I don’t enjoy going to school all the time so I occasionally skip school and stay at the playground all day, but I don’t tell Pa. One thing I do like about school is the uniform I get to wear this year. My uniform consists of a white shirt with puffy, short sleeves and a short, blue pleated skirt. I think it is very pretty, though sometimes I worry that my skirt is too short. A few days ago, while I was playing hopscotch with my friends, a boy came over and tried to lift up my skirt. I was so angry that I pushed him really hard, harder than I thought I could. He fell and I ran away, my knees weak. I think the boy is afraid of me now.

Most Sundays after we’ve finished all our homework, Pa rewards us by taking us swimming at the club. I love to swim, but I am not allowed in the deep end. The pool at the club is very big, so even in the shallow end there is plenty of room to play and splash water in Chou’s face. After Ma helps me put on my bathing suit, which is a very short pink dress with the legs sewn in, she and Pa go to the second floor and have their lunch. With Keav keeping an eye on us, Pa and Ma wave from their table behind the glass window. This is the first time I saw a Barang.

“Chou, he is so big and white!” I stop splashing water long enough to whisper to her.

“He’s a Barang. It means he’s a white man.” Chou says with a smirk, trying to show off her age.

I stare at the Barang as he walks onto the diving board. He is more than a foot taller than Pa, with very hairy long arms and legs. He has a long, angular face and a tall, thin nose like a hawk. His white skin is covered with small black, brown, and even red dots. He wears only underwear and a tan rubber cap on his head, which makes him look bald. He dives off the diving board, enter the water effortlessly, and creates very little splashing.

As we watch the Barang float on his back in the water, Keav chides Chou for giving me the wrong information. Dipping her freshly painted red toenails in and out of the water, she tells us “Barang” means he’s French. Because the French have been in Cambodia so long, we call all white people “Barang,” but they can be from many other countries, including America.

takeover

April 17, 1975

It is afternoon and I am playing hopscotch with my friends on the street in front of our apartment. Usually on a Thursday I would be in school, but for some reason Pa has kept us all home today. I stop playing when I hear the thunder of engines in the distance. Everyone suddenly stops what they are doing to watch the trucks roar into our city. Minutes later, the mud-covered old trucks heave and bounce as they pass slowly in front of our house. Green, gray, black, these cargo trucks sway back and forth on bald tires, spitting out dirt and engine smoke as they roll on. In the back of the trucks, men wearing faded black long pants and long-sleeve black shirts, with red sashes cinched tightly around their waists and red scarves tied around their foreheads, stand body to body. They raise their fists to the sky and cheer. Most look young and all are thin and dark-skinned, like the peasant workers at our uncle’s farm, with greasy long hair flowing past their shoulders. Long, greasy hair is unacceptable for girls in Cambodia and is a sign that one does not take care of her appearance. Men with long hair are looked down upon and regarded with suspicion. It is believed that men who wear their hair long must have something to hide.

Despite their appearance, the crowd greets their arrival with clapping and cheering. And although all the men are filthy, the expression on their faces is of sheer elation. With long rifles in their arms or strapped across their backs, they smile, laugh, and wave back to the crowds the way the king does when he passes by.

“What’s going on? Who are these people?” my friend asks me.

“I don’t know. I’m going to find Pa. He will know.”

I run up to my apartment to find Pa sitting on our balcony observing the excitement below. Climbing onto his lap I ask him, “Pa, who are those men and why is everybody cheering them?”

“They are soldiers and people are cheering because the war is over,” he replies quietly.

“What do they want?”

“They want us,” Pa says.

“For what?”

“They’re not nice people. Look at their shoes—they wear sandals made from car tires.” At five, I am oblivious to the events of war, yet I know Pa to be brilliant, and therefore he must be right. That he can tell what these soldiers are like merely by looking at their shoes tells me even more about his all-powerful knowledge.

“Pa, why the shoes? Why are they bad?”

“It shows that these people are destroyers of things.”

I do not quite understand what Pa means. I only hope that someday I can be half as smart as he is.

“I don’t understand.”

“That’s all right. Why don’t you go and play; don’t go far and stay out of people’s way.”

Feeling safer after my talk with Pa, I climb off his lap and make my way back downstairs. I always listen to Pa, but this time my curiosity takes over when I see that many more people have gathered in the street. People everywhere are cheering the arrival of these strange men. The barbers have stopped cutting hair and are standing outside with scissors still in their hands. Restaurant owners and patrons have come out of the restaurants to watch and cheer. Along the side streets, groups of boys and girls, some on foot, some on motorcycles yell and honk their horns as others run up to the trucks, slapping and touching the soldiers’ hands. On our block, children jump up and down and wave their arms in the air to greet these strange men. Excited, I cheer and wave at the soldiers even though I don’t know why.

Only after the trucks have passed through my street and the people quiet down do I go home. When I get there, I am confused to find my whole family packing.

“What’s going on? Where’s everybody going?”

“Where have you been? We have to leave the house soon, so hurry, go and eat your lunch!” Ma is running in every direction as she continues to pack up our house. She scurries from the bedroom to the living room, taking pictures of our family and the Buddha off the walls and piles them into her arms.

“I’m not hungry.”

“Don’t argue with me, just go and eat something. It’s going to be a long trip.”

I sense that Ma’s patience is thin today and decide not to press my luck. I sneak into the kitchen prepared not to eat anything. I can always sneak my food out and hide it somewhere until it is found later by one of our helpers. The only thing I am afraid of is my brother Khouy. Sometimes, he waits for me in the kitchen to make me eat proper food—or else. Heading to the kitchen, I poke my head into my bedroom and spy Keav shoving clothes into a brown plastic bag. On the bed, Geak sits quietly playing with a handheld mirror while Chou throws our brushes, combs, and hairpins into her school bag.

As quiet as I can be, I tiptoe into the kitchen and sure enough, there he is. He is feeding himself with his right hand while his left gently touches a slim bamboo stick lying on the kitchen table. Next to the bamboo stick is a bowl of rice and some salted eggs. Most evenings, the younger kids in the house will gather in the kitchen to study Chinese, and a tutor uses the bamboo stick to point out characters on the blackboard. In the hands of my brother, it is used to educate us about something else entirely. I was taught to fear what my brother will do with it if I do not do as I am told.

I give Khouy my most charming smile, but this time it does not work. He sternly tells me to wash up and eat. In moments like these I fantasize about how much I hate him. I cannot wait until I am as strong and as big as he is. Then I will take him on and teach him many lessons. But for now, since I am the smaller one, I have to listen to him. I whine and sigh with every bite of food. Every time he looks elsewhere I stick out my tongue and make faces at him.

After a few minutes, Ma rushes into the kitchen and begins to toss aluminum bowls, plates, spoons, forks, and knives into a big pot. The silverware clangs noisily, making me jittery. Then picking up a cloth bag, she throws bags of sugar, salt, dried fish, uncooked rice, and canned foods into it. In the bathroom, Kim throws soap, shampoo, towels, and other assorted items into a pillowcase.

“Aren’t you finished yet?” she asks me, out of breath.

“No.”

“Well, you better go wash your hands and get into the truck anyway.”

Glad to escape from Khouy, who sits glaring at me, I hurriedly jump off my chair and head for the bathroom.

“Ma, where are we going in such a hurry?” I yell out to her from the bathroom as Kim leaves with his bag.

“You’d better hurry and change your shirt, the one you are wearing is dirty. Then go downstairs and get into the truck,” Ma tells me as she turns away without answering. I believe it is because of my age that no one ever pays any attention to me. It is always so frustrating to have your questions unanswered time and time again. Fearing more threats from Khouy, I walk to my bedroom.

The bedroom looks as if a monsoon has passed through it: clothes, barrettes, shoes, socks, belts, and scarves are strewn everywhere—on the bed that Chou and I share as well as on Keav’s bed. Quickly, I change out of my brown jumper and into a yellow short-sleeve shirt and blue shorts I pick up off the floor. Once finished, I walk downstairs to where our car is. Our Mazda is black, sleek, and much more comfortable than riding in the back of our truck. Riding in the Mazda sets us apart from the rest of the population. Along with our other material possessions, our Mazda tells everybody we are from the middle class. Despite what Ma tells me, I decided to head toward our car. I begin to climb into the Mazda when I hear Kim call out to me.

“Don’t get in there. Pa said we’re leaving the Mazda behind.”

“Why? I like it more than the truck.”

Again, Kim is gone before answering my question. Pa bought the truck to use for deliveries for the import/export business he had briefly gone into with friends. The business never got going, so the truck has been sitting in our back alley for many months. The old pickup truck creaks and squeaks as Khouy throws a cloth bag onto its floor. In front, Pa ties a large white cloth to the antenna while Meng ties another piece to the side mirrors. Without any words, Khouy picks me up and loads me onto the back of the truck filled with bags of clothes and pots and pans and food. The rest of my siblings climb on board and we drive off.

The streets of Phnom Penh are noisier than ever. Meng, Keav, Kim, Chou, and I sit in the back of the truck while Pa drives with Ma and Geak in the cab. Khouy follows us slowly on his motorcycle. From up on our truck, we hear the booming roars of cars, trucks, and motorcycles, the jarring rings of the cyclos’ bells, the clanking of pots and pans banging against each other, and the cries of people all around us. We are not the only family leaving the city. People pour out of their homes and into the streets, moving very slowly out of Phnom Penh. Like us, some are lucky and ride away in some kind of vehicle; however, many leave on foot, their sandals flapping against the soles of their feet with every step.

Our truck inches on in the streets, allowing us a safe view of the scene. Everywhere, people scream their good-byes to those who choose to stay behind; tears pour from their eyes. Little children cry for their mothers, snot dripping from their noses into their open mouths. Farmers harshly whip their cows and oxen to pull the wagons faster. Women and men carry their belongings in cloth bags on their backs and their heads. They walk with short, brisk steps, yelling for their kids to stay together, to hold each other’s hands, to not get left behind. I squeeze my body closer to Keav as the world moves in hurried confusion from the city.

The soldiers are everywhere. There are so many of them around, yelling into their bullhorns, no longer smiling as I saw them before. Now they shout loud, angry words at us while cradling rifles in their arms. They holler for the people to close their shops, to gather all guns and weapons, to surrender the weapons to them. They scream at families to move faster, to get out of the way, to not talk back. I bury my face into Keav’s chest, my arms tight around her waist, stifling a cry. Chou sits silently on the other side of Keav, her eyes shut. Beside us, Kim and Meng sit stone-faced, watching the commotion below.

“Keav, why are the soldiers so mean to us?” I ask, clinging even more tightly to her.

“Shhh. They are called Khmer Rouge. They are the Communists.”

“What is a Communist?”

“Well, it means. … It’s hard to explain. Ask Pa later,” she whispers.

Keav tells me the soldiers claim to love Cambodia and its people very much. I wonder then why they are this mean if they love us so much. I cheered for them earlier today, but now I am afraid of them.

“Take as little as you can! You will not need your city belongings! You will be able to return in three days! No one can stay here! The city must be clean and empty! The U. S. will bomb the city! The U. S. will bomb the city! Leave and stay in the country for a few days! Leave now!” The soldiers blast these messages repeatedly. I clap my hands over my ears and I hide my face against Keav’s chest, feeling her arms tighten around my small body. The soldiers wave their guns above their heads and fire shots into the air to make sure we all understand their threats are real. After each round of rifle fire, people push and shove one another in a panicked frenzy trying to evacuate the city. I am riddled with fear, but I am lucky my family has a truck in which we can all ride safely from the panicked crowds.

[/lyrics]

DETAILS

TITLE:

Author:

Language: English

ISBN:

Format: TXT, EPUB, MOBI

DRM-free: Without Any Restriction

SHARE LINKS

Mediafire (recommended)Rapidshare

Megaupload

No comments:

Post a Comment